My father wore a face like thunder as he flicked through a week’s worth of accumulated post. Shouty junk mail mixed in with even shoutier red letters and envelopes stamped “urgent” or “overdue”.

Trouble was brewing.

We all knew the signs.

It was part of the normal household cadence. Sunday nights were the time when he stalked into his study armed with a handful of bills, his chequebook, and a large alcoholic beverage. Half an hour later he would stagger out wild-eyed and spoiling for a fight, like a punch drunk boxer who just didn’t know when to quit. He would emerge with an empty glass and an emptier bank account.

Time to make ourselves scarce. Experience had taught us that our health, happiness, and general wellbeing benefited greatly from being out of reach on Sunday evenings.

Trying my best to be invisible, I silently edged towards the back door. My younger brother was only a pace behind.

My father grunted, then suddenly looked up. Speared me with his eyes. We froze like statues, sculpted with matching guilty expressions the likes of which can only be produced by boys caught in the act.

He held out a letter. “This one is for you”.

I blinked. Cognitive dissonance ricocheting around the inside of my skull. My lizard brain screamed a full-throated plea to run. My inner saboteur was sorely tempted by curiosity of the unknown. Meanwhile, the thinking part of my brain was perplexed.

Was it a game?

A mistake?

A trap?

Apart from a couple of random corporate Christmas cards from a faceless whole-of-life insurance broker whom I had never met, this was the first letter I had ever received.

My brother bolted as I stood paralysed by indecision. Darwinism at work. You don’t have to be the fastest, just not the slowest.

After a moment, my father made the decision for me. He thrust the letter into my hand, then stoically headed for his study with the sort of enthusiasm displayed by condemned prisoners and peak hour commuters.

Clutching the envelope to my chest, I too escaped outside.

Exponential growth

A few moments later I sat perched on the roof of my neighbour’s garage. Out of sight, out of mind.

With trembling fingers, I tore open the envelope and extracted a single sheet of folded paper. My name and address were prominently printed at the top in a cramped formal typewriter font that managed to convey a sense of harried seriousness. It was hard to read.

Unfolding the letter revealed an oddly proportioned piece of paper inexplicably decorated with alternating pink and white lines.

The logo in the corner was the same as the one used by the bank branch I had nervously ventured into a few weeks ago to open my first ever bank account. The cheap bastards had not even given me a money box in return for the deposit of my one-dollar coin. “Budget cutbacks” the bank teller had shrugged somewhat apologetically.

The top of the page boldly proclaimed the words “Bank Statement”. Having no idea what a bank statement was, I tried and failed to read it like a story.

Stepping back, I looked in bewilderment at a bizarre array of numbers, alphanumeric codes, and a collection of what I was pretty sure were made-up words. What the hell was a debit?

One of the lines began with what looked like a date. I traced my finger along a pink stripe and read the text “BALANCE BROUGHT FORWARD”, followed by the number $1.00.

Counting backwards on my fingers, I determined the date on the page was the same day that I had visited the bank. I tentatively concluded that $1.00 was my dollar coin. “Brought forward” was certainly a weird way to describe my waiting in the queue before handing my coin to the bank teller.

The next line contained a made-up word and the number $3.24.

I had no idea what the made-up word meant, but I recognised the amount. It was what my new boss had promised to pay me for spending an afternoon each weekend delivering junk mail to hundreds of houses in my neighbourhood.

Adjusting for inflation and exchange rates, that was the equivalent of £4.18 today.

Less than minimum wage.

Dwelling firmly down in the “exploit me” territory inhabited by apprentices, interns, food delivery riders, uber drivers, and those poor unfortunates who are employed under zero-hour contracts.

I grinned. Fist pumped. Did the victory dance. Nearly fell off the garage roof.

In the space of a single day, my net worth had more than tripled.

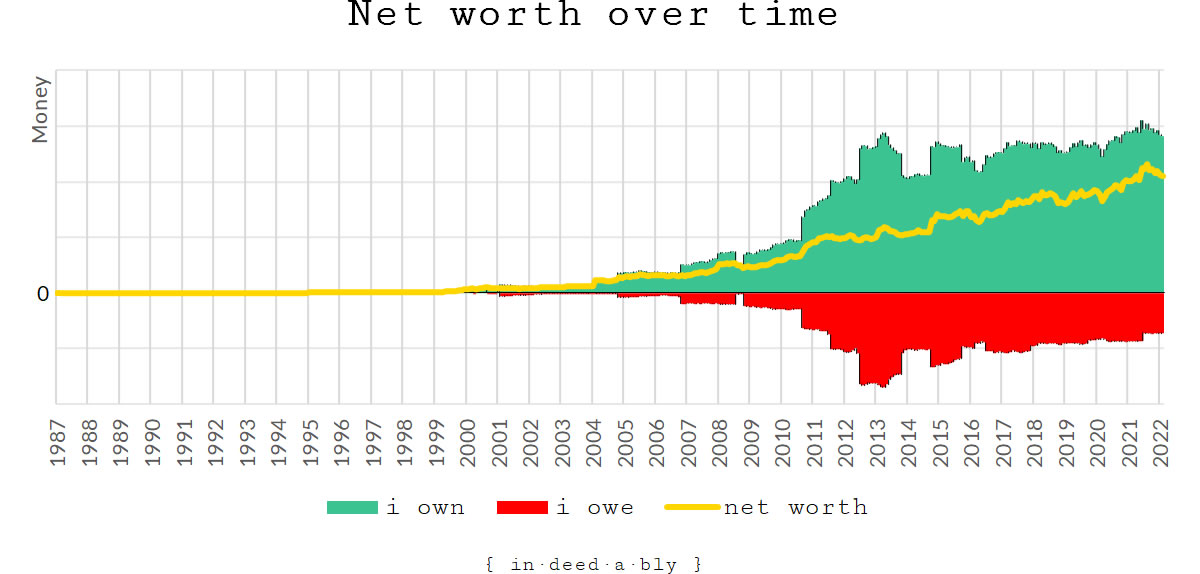

History tells us that feat would never be repeated.

A couple of weeks later my net worth had doubled again.

If that is all it took then this money caper was easy! The ten-year-old me couldn’t comprehend why my father found it so stressful. Little did I know then, that bank statements could contain two columns of figures: credits and debits. Inflows and outflows.

What you keep is determined by the deceptively simple equation of income minus expenses.

Simple indeed.

Easy? Not so much.

It’s complicated

Our relationship with money is often a complicated one.

For those who have none, money can be a source of anger, discontent, and fear. An actual matter of life or death.

Having some money often instigates an endless thirst for a having bit more. Money shifts from being a survival tool to a goal. A means of keeping score. “Greed is good”. “Level up”. “Always be hustlin’”.

By the time we have “enough“, money starts to lose its lustre as a motivating factor. A little bit more makes no tangible difference. The dawning realisation that the unit of measure for wealth is time, not money.

Having a lot is a nice problem to have. The money itself becomes relatively meaningless. Arbitrary numbers that will only be missed in their absence. Goals shift towards control, contribution, legacy, meaning, popularity, power, status, and making a difference.

Every so often I find myself getting frustrated by my own lack of tangible financial progress.

My net worth is roughly the same as it was two years ago. Which was not materially different to two years before that.

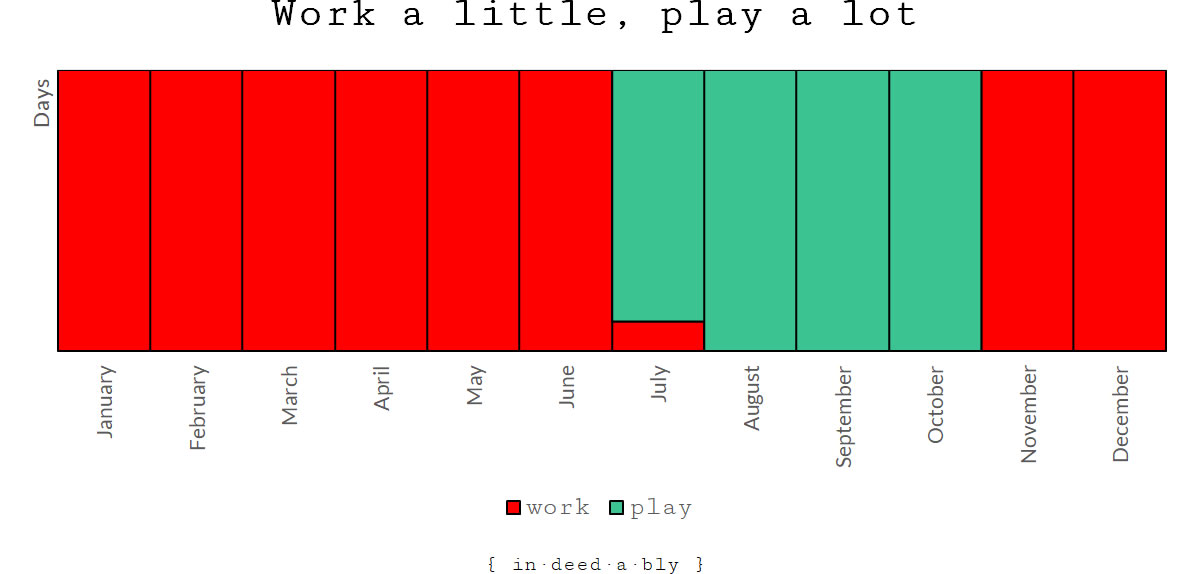

In my case, this is by design. My winter working hibernations are engineered to bridge the gap between lifestyle costs and passive income. A short sharp stint each winter, working as a professional meeting attendee, buys me the luxury of enjoying the summers off.

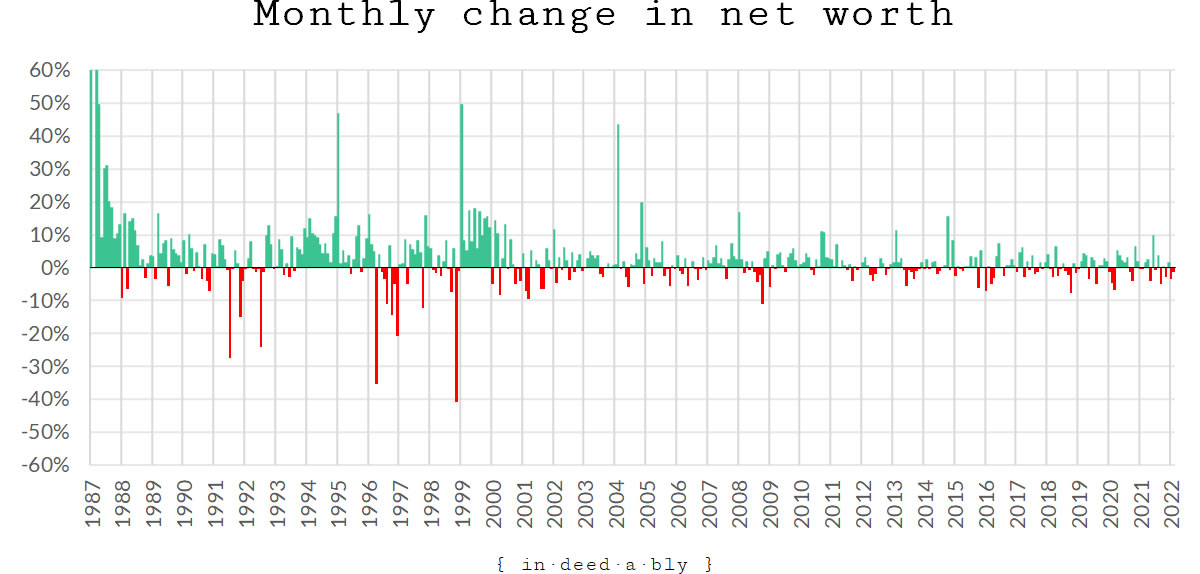

However, there is a fascinating paradox at the heart of personal finance. The larger our net worth, the smaller the shifts in the needle.

This is mostly a good thing. It provides resilience to the randomness of life. Smoothing out the ride. Overcoming the fragile existence of those who are just scraping by, wondering which red letters to pay today and sweating on which may not wait until the next paycheque.

My childhood experiences of 100+% intraday increases in net worth were entertaining but never repeated.

Conversely, the few times I have experienced a 30-40% fall in net worth were decidedly unsettling. The sort of thing that spoils your day. Not an experience I would care to repeat.

However, a higher net worth also raises the bar.

Those mile markers charting our progress become spaced ever further apart.

Arbitrary number milestones become harder to attain. Yet somehow wealth seems to have a way of building momentum and achieving them anyway, though seldom as swiftly as we would like.

Those psychological high fives we receive by attaining our financial goals arrive less often. Each successive one has less meaning. The law of diminishing returns.

This week I spent a bit of time puzzling over this feeling that I was treading water.

Was it real or had I imagined it? An actual problem, or merely a perceived problem?

I plotted my cash inflows against outflows, adjusting both for inflation to make a comparison between periods realistic. The orange break-even line tells me that more often than not I earned more than I had spent.

Analysing the underlying numbers revealed that the major determining factor was the cost of childcare. Private nurseries are eye-wateringly expensive. After school nannies less so. State school places are free. This is the price of living in the big city, but a problem that resolves itself in time.

Frugalistas and FIRE devotees would be horrified at my savings rate. That arbitrarily defined measure that defies comparison due to inconsistent methods of calculation.

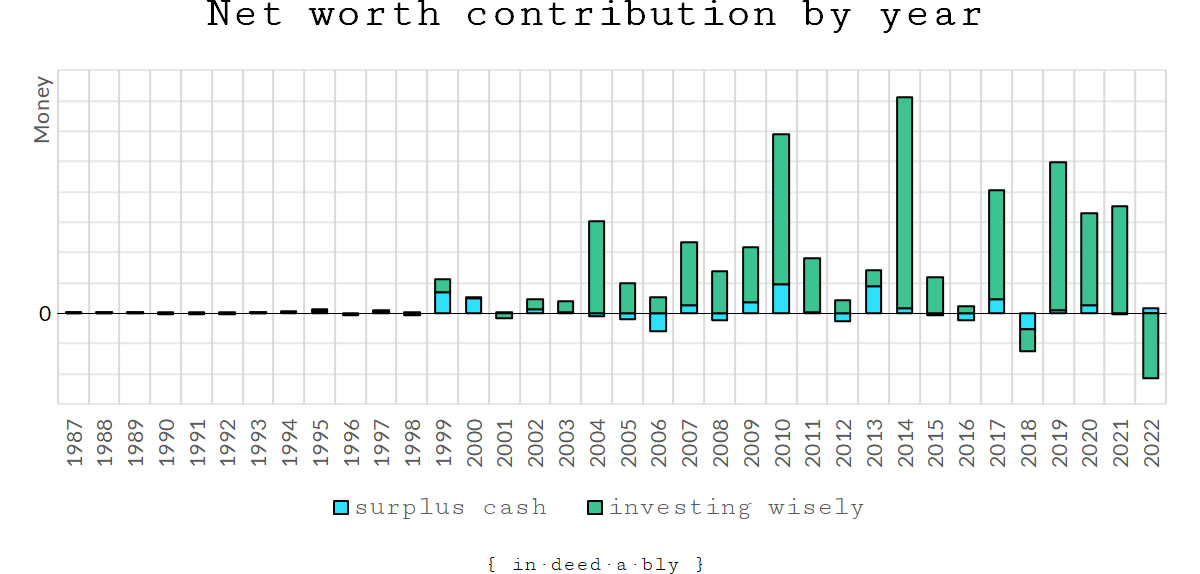

However, I’ve long held the belief that the sustainable path to wealth is investing in myself to maximise the marketable value of my skills and experience. Then investing the proceeds wisely.

Ultimately it is capital gains that make us rich, though cashflow determines whether we feel rich.

The illusion of progress

I suspect that is the root cause behind this feeling of having stalled.

In choosing to work just enough to bridge the gap between my passive income streams and my lifestyle costs, I have prioritised control of my time over maximising my net worth.

That comes at the psychological cost of my bank balance not routinely soaring each month with the deposit of a fat pay packet like it did in years past.

Nor does my net worth steadily ratchet up as it once did.

Once upon a time, topping up my investment accounts with surplus cashflow would make a tangible difference. Today, the impact of market fluctuations far exceeds the size of any additional capital contribution I may choose make.

Instead, I experience a lumpy earnings profile.

Dividends sporadically are paid out. Rental income trickles in around maintenance costs and void periods. Occasionally I distribute some retained earnings from my business profits to replenish my coffers.

I could probably manufacture a regular pay packet for myself. Choose psychological reward over tax efficiency. Smooth out my earnings profile. There would still be “enough”, but enough wrapped in an illusion of progress.

A salve to my ego.

A means of silencing the voice of my inner saboteur.

Not a real difference, but the appearance of a difference. Maybe that will address the stalled feeling?

Perhaps I am just feeling the call of the approaching Springtime. The trees in my neighbourhood are blossoming. Soon the first of the daffodils will appear in the park. Longer days. Warmer weather. The tempting lure of a seasonal semi-retirement.

But we all know that retirement can’t fix you.

If this feeling is the biggest thing I have to worry about, then that is a fortunate problem indeed.

Yet a problem it remains.

References

- Gov.uk (2020), ‘National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage rates‘

Steveark 7 February 2020

I used to get a feeling of satisfaction as my pay kept going up. I also enjoyed seeing my net worth increase . Now that I’ll never need to earn additional money it’s impossible to feel stalled. Money has just ceased to be of concern because it’s abundant. Now it’s just a matter of deciding how to best spend my day. And that feels more like an adventure than a problem.

{in·deed·a·bly} 7 February 2020 — Post author

You may be onto something there Steveark.

The problem could be as simple as applying the wrong measures, looking in the wrong place for that feeling of progress.

Keeping score with savings rates or net worth may make sense during the accumulation phase. It makes much less sense during the subsequent preservation or decumulation phases.

Phil Money Mongoose 10 February 2020

I think that’s an easy trap to fall into. A bank balance is a concrete easy to measure item that you can also compare against other people. Finding such a measure for happiness, well-being or [insert tree-hugging measure here] could be helpful.

{in·deed·a·bly} 10 February 2020 — Post author

Or learning to accept that many of the important things aren’t tangible, and often can’t be measured. Nor should they be for that matter.

Thanks Phil.

[HCF] 10 February 2020

Do you think it is a problem if someones thoughts gets more and more shifting towards “control, contribution, legacy, meaning, and making a difference” despite being pretty far from the having too much and even from the having enough point? I think this is something what comes with age not necessarily with financial progress. Am I wrong?

{in·deed·a·bly} 10 February 2020 — Post author

I think it is a maturity thing more than an age thing, HCF.

Money is a enabler, not a goal. It isn’t the thing, but rather the thing that gets a person to the thing.

I think a lot of PF bloggers start out blindly chasing arbitrary numbers. Debt free. Paid off house. Million dollars. Whatever. Then once they start to hit them, they realise they don’t feel any different than they did before. The focus gradually shifts from worth to value.

Once that happens the realisation sinks in that most things people dream of doing after financial independence they can already be doing in some form today if they just changed their prioritisation and time investment decisions.

That leads to a more balanced outlook.

David Andrews 11 February 2020

I didn’t fee any different when I hit the milestones you listed. Paid off house at 36, debt free at 37, paper millionaire at 40, paid cash for my half of a second house at 43. I vaguely recall a long ago interview with a Concorde pilot. When questioned about what it feels like when you break the sound barrier he replied that “it wasn’t that noticeable”. That’s pretty much what it felt like to hit each of the goals I listed. Achieving the things that I’ve listed just mean I have a bit more choice in what I do with my time in the future. I’ve arranged my finances so my inflows hover around the taxable threshold. I don’t really notice when I’ve been paid apart from when I check my pension statement and see (hopefully) an increase each month reflect my additional contributions. Sadly, this the triggers anxiety of breaching the LTA or pension schemes going bust but that’s a different story.

{in·deed·a·bly} 11 February 2020 — Post author

I concur.

I think the only time I was ever nearly as excited as that first $3.24 pay packet was the day my first invoice was paid once I had started working for myself. That wasn’t so much because it meant my business looked slightly more viable, but rather because I could then afford to eat!

GentlemansFamilyFinances 10 February 2020

Very thought provoking article.

When you say that it’s your capital gains that make you rich I can agree with that – but cash flow can make you feel poor.

I spent most of the last 4 years paying everything into the salary sacrifice pension and our cost of living and nanny (worth it but costly) meant that we were on the face of it treading water in take home pay terms.

The difference is that I’ve always got money flowing in and out of places (meddling with P2P does that) and it’s easier to withstand the slow bleed of a negative cashflow if you have a war chest behind you.

That’s the strategy I’ve had – it works – but maybe not for everyone and I’ve never been in a position where we’ve had no work income so more a peace-fund than war chest.

{in·deed·a·bly} 10 February 2020 — Post author

Thanks GFF. Cash flow certainly plays a big part in how well off we feel.

The nice thing about having the financial cushion you refer to is we have the tools required to address that cash flow. To turn a trickle into a flood if we so desire.

My point was that as a kid, when everything seemed simple, the bank account was constantly being topped up from external sources so I felt like I was making tangible progress. The same feeling doesn’t occur when share or property prices move, even if that movement is ±£50,000 in a given month. That is “funny money“, unrealised paper gains that won’t pay for the groceries in the same way a pay packet might.

GentlemansFamilyFinances 10 February 2020

You might also be beyond the point of marginal utility with money…

{in·deed·a·bly} 11 February 2020 — Post author

That would be the point of having “enough”.

Similar to what HCF commented above, I may have peaked early. Comfortably FI in the vast majority of the globe… but not where I currently live. Able to adjust the levers to hugely reduce my outgoing cash flows… but not in my current neighbourhood, or with my current childcare arrangements.

It is all about choices and priorities. Learning to recognise that is half the battle.

GentlemansFamilyFinances 11 February 2020

I have managed to do a bit of geo-arbitrage to avoid very HCOL or Low Living Standards (as I’ve been from people who live in London/SE).

Being well off but not spending it and living within your means is easier in a LCOL area but not easy overall.