Adrian strolled into the interview room. He looked lean, tanned, and somewhat uncomfortable in his grey business suit.

Hands shaken. An arcane custom used to demonstrate that participants weren’t holding swords.

Introductions made. Names and job titles exchanged, then instantly forgotten.

Seats taken. Interviewers on one side of the table. Candidate on the other. Us against them.

The project manager launched into a well-rehearsed narrative about the client, the team, and the role.

Adrian listened politely as the basic facts from the client’s website and job description were rehashed and mangled.

Anyone who has been contracting for a while quickly learns that job interviews are more about ritual than truth.

An intricate dance between interviewer and interviewee.

Job specifications always contain an “other duties as required” clause, rendering the remainder of the duty statement rose-coloured fiction. Blind optimism. Well-intentioned half-truths. Sometimes outright lies.

The dance steps are simple. The client has a problem. They seek an expert to make it go away.

Sometimes the client doesn’t understand the problem. Not really. If they did, they could solve it for themselves.

Which creates some challenges for the ritual format. Can the interviewer ask good questions? Even if they do, can they competently assess the calibre of the answers received?

The honest answer to one or both those questions is often no.

Think about that for a moment. How would you interview a financial planner? Heart transplant surgeon? Master builder? Personal trainer? Tax accountant?

All specialist skills, the majority of which fall outside your sphere of competence.

Services you may require, but are not qualified to judge.

The project manager asked Adrian some questions that he had found on the internet, but didn’t understand himself.

Adrian responded using small words and short sentences. Tailoring his answers to both educate and inform the interview panel. Without being condescending or making them feel stupid.

After about 20 minutes the dance had concluded, and the interview panel was at an impasse.

Adrian seemed confident. Knowledgeable. Personable. He had passed the green hair test. Appeared easy-going enough to fit in with the team culture, yet resilient enough to survive the institutional politics.

Most importantly, he had made friends with the interview panel and created the impression that he was a safe pair of hands.

Their problem was they simply couldn’t determine whether he could help them solve their problem.

Cake rustling

At that moment the project manager spied me walking past the glass interview room wall. He leapt out of his chair to intercept me as I went past the door.

I had just sneakily liberated a slice of delicious cinnamon cake from the board room. I hadn’t been caught taking it. I hadn’t expected to be caught eating it.

The project manager glanced at the cake and raised an eyebrow.

It was the client CEO’s favourite.

Specially ordered from a Danish bakery.

Exclusively procured for board meetings.

Sharing with the peasantry was strictly verboten. Sharing with a humble consultant? No chance!

Which I figured made it fair game. A challenge.

Except now I had been busted.

The project manager quickly outlined his problem. A vacancy he needed to fill but didn’t understand. A candidate who seemed like a good fit, but they needed to be sure he could get the job done.

He made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. Vet the candidate and my cake rustling would be forgotten.

I strolled into the interview room. Hands. Introductions. Seats. Adrian must have experienced déjà vu.

Not knowing anything about the specific role or the candidate, I made a preposterous statement about an issue that would be fundamental to the project’s success.

Up was down.

Day was night.

The sun rises in the West and sets in the East.

Then I asked Adrian what he thought about that.

Adrian grinned. Then proceeded to methodically, yet diplomatically, tear apart my outrageous assertion. Explaining exactly why it was wrong, how he could prove it, and what the right answer actually was.

In doing so he articulately demonstrated that he understood the exam question and the value chain essential for succeeding in the role.

Next, I asked a question Adrian couldn’t possibly know the answer to. I didn’t much care what he came up with, but wanted to observe his approach to problem-solving.

While Adrian was answering I skimmed through a copy of his resume that had been sitting on the meeting room table.

Resumes are fine works of fiction.

An advertisement for a candidate’s skills and experience, that exist solely to secure an interview.

The dates and places can be readily verified with effort. The boasts and claims difficult to disprove.

In days long ago, it was possible to phone up a referee and receive a somewhat candid assessment of the candidate’s past job performance and suitability for the role they had applied for.

Generations of discrimination, reputational harm, and unfair restraint of trade lawsuits have brought that practice to an end.

Today many sites even forbid interview small talk about families or living locations, out of fear of being sued for discrimination by unsuccessful candidates.

Did the applicant miss out because there were stronger candidates? Or was it the risk of unreliability due to the tribe of young kids they had at home?

Were they unqualified? Or were they rejected due to the unsustainably long daily commute they were proposing to subject themselves to?

Adrian’s resume contained an intriguing work pattern.

University. Year log gap. Job. Half year gap. Job. Half year gap. Job. Year long gap. Job. Half year gap.

I interrupted Adrian’s excellent, though long-winded, problem-solving approach answer to ask about all the employment gaps.

“I like to go hiking” he replied. Factual. Neither surprised nor defensive. Clearly, this wasn’t the first time he had experienced this conversation.

“For six months? A year?”

“It was a long walk.”

It turned out Adrian had trekked 3,000 kilometres along the Appalachian Trail.

A year later he returned to walk a further 1,900 kilometres along the Pacific Northwest Trail.

The next year he did the 750 kilometre Camino de Santiago in Spain. Had a bit of a rest. Then proceeded to walk another 600 kilometres to Lisbon.

Another year, another walk.

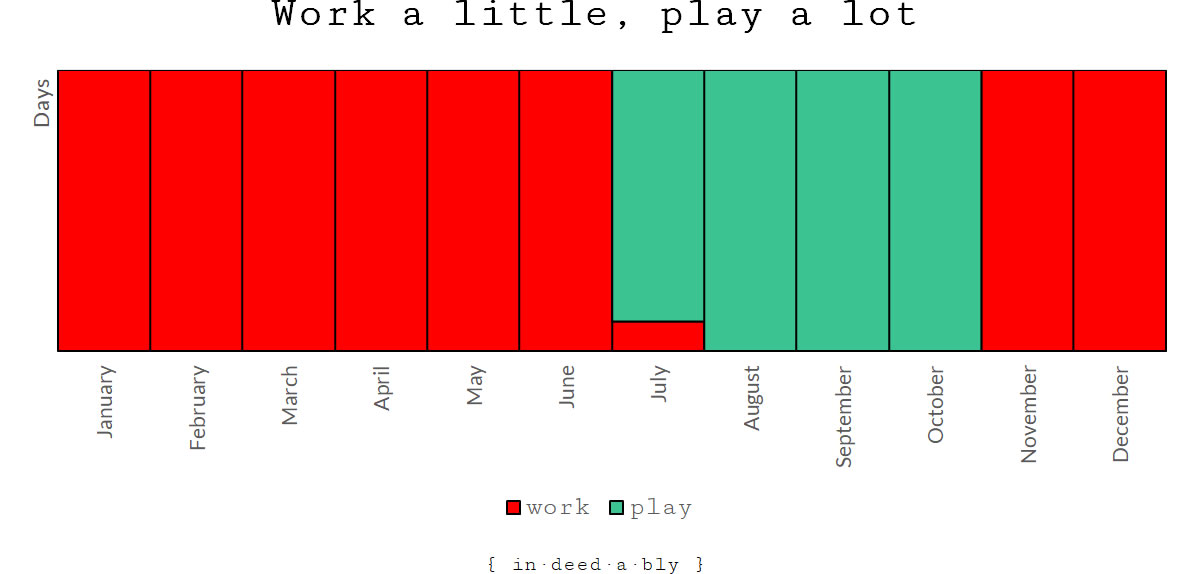

A deliberate lifestyle pattern emerged.

Work a contract to replenish the bank account. Then go walkabout.

Adrian had done an awe-inspiring amount of walking. However, the thing I found truly impressive was the conscious prioritisation process he applied to how he invested his time. Working as an enabler to doing what he truly loved: walking.

I told the project manager I would hire Adrian on the spot. He did so.

Three months later Adrian had proved to be as good as he appeared in the interview.

The project he had been hired to work on was failing spectacularly. This was hardly a surprise, given how hopelessly out of his depth the incompetent project manager had been.

From the rubble, I poached Adrian to work in one of my teams.

Which he did. For three months. Before he went headed off to trek the length of New Zealand.

Upon his return, I hired Adrian again. A pattern that repeated for several years. He was great at what he did, and his lengthy absences were both predictable and able to be planned around. It was an arrangement that worked well for both of us.

Alas, all good things must come to an end. Marriage, mortgage, and children clipped Adrian’s wings. He sold his soul and traded his hiking boots for a lucrative permanent job at an investment bank.

He must really love his family. Every time I catch up with him, the poor guy seems miserable.

Lifestyle design

Adrian’s ability to successfully return to the workforce time and again demonstrated that taking career breaks was survivable.

The ease of that re-entry differed markedly, depending upon the buoyancy of the job market and the demand for his niche skills. Sometimes he walked straight back into a role. Other times it took a couple of months to find a client willing to look past his resume gaps.

The lesson I took from Adrian’s experience was that providing he kept his skills marketable and didn’t let his network grow stale, he could generally find a client who was willing to purchase his time.

My own seasonal working pattern was partly inspired by Adrian’s conscious approach to lifestyle design.

Work a little, play a lot.

Unlike Adrian, I chose to adopt an unconventional working pattern only once I had established a strong reputation within my niche.

I also ensured that I had first established a financial cushion sufficient to support both myself and my family for an extended period of time. The economic gods have not always smiled favourably upon my periodic desire to seek out a new client project.

After a couple of decades surfing the timeless waves of economic boom and bust, I have learned to appreciate just how little personal control we each have over market conditions when we change jobs.

Much of the time we successfully make the leap towards bigger and better things.

Occasionally we will be pushed.

Sometimes unexpectedly,

There will always be another job for those who want one. Until there isn’t.

Just not always when or where we want them.

Successful application of a seasonal working pattern requires flexibility. Particularly around industry preference and earnings expectation.

The largest risk is that the market no longer wants to buy what you are selling.

For those paying attention, these are predictable slow-moving trends. However, dropping your guard or taking your eye off the horizon can easily transform a voluntary short term career break into an abrupt and unplanned career end.

No gold watch.

No ticker-tape parade.

Just a silent fade into obsolesce.

Survivable, providing you are young enough to re-skill and willing to start over. Later in life, your mileage may vary.

travelprof 12 January 2020

As a keen hiker and traveller now in my 4th decade myself, I wish I had carved out my own niche to be able to do what Adrian did. I had to quit my roles each time I did my gap years. Now I face hidden ageism when I interview for roles and the date gaps in my CV don’t help when I speak to often younger interviewers who have never taken time out of the workplace.

At the same time I wish I had saved a lot more of my earnings in my 20s and 30s to give me a bit more of a safety net.

Thanks for the article, really made me reminisce, and consider how I can turn things around to continue on my own FIRE path, but with adventures along the way while I still have energy.

{in·deed·a·bly} 12 January 2020 — Post author

Thanks travelprof.

That opportunity cost decision is a tricky one. We all know that investing, compounding, and leaving it alone achieves the optimal financial outcome. Yet by the time we have “enough” we’re most likely too old to enjoy the type of adventures Adrian had undertaken as a younger man.

Where the right balance falls between living for today and saving for tomorrow differs from person to person. Getting that balance right is one of the hardest parts of enjoying the journey towards a sustainable Financial Independence.

For what it is worth, in my experience the ageism thing happens regardless of whatever lifestyle choices a person has made. Once a person has accrued some grey hair and wrinkles it just becomes an unfortunate part of the game.

Former Button Pusher 15 January 2020

Hey, I appreciate your terse thoughtful posts, both the content and meditative expression.

As a just-FIREd banking contractor, there is much to relate to in this one.

In my younger contracting days, I would occasionally meet a contractor who spent three months skiing or travelling each year. Met fewer of them as the years went by though, probably as my cohort aged and acquired responsibilities.

That intermittent hedonism never seemed like a serious option for me : I was always driven by the fear of uncertainty and the greed of catching raining soup, to carry on grafting. On to the next contract. Then the next. Any break was not savoured, only anxiously endured: an attitude counterproductive of joy. You describe the various vagaries of the market well – there is much else in the hiring cycle that is also driven by factors outside of ones control, and it is futile to stress and cramp other activities in order to remain instantly available, I eventually learned.

At the end, I think I timed my exit well: I operate at the end of the market bitten by IR35 and have made my FIRE number just before that becomes more irksome. Also, I ceased to enjoy the challenges. So, exit stage left. Hopefully not pursued by a bear (market).

I don’t regret the missed holidays: a city break to Prague can now always be taken, or now an open-ended trip to France. I do regret the endless late evenings working / using weekends just to rest and recover, because of the impact on family time: that really is irrecoverable.

Spending time with people to love is for me the ultimate joy. Spending time to give those people a secure life, has unfortunately traded off against Goal#1, but one makes choices and accepts the tradeoffs.

You seem to be finessing those tradeoffs with more sophistication than I managed. Keep it up and keep dropping the insights.

{in·deed·a·bly} 15 January 2020 — Post author

Thanks Former Button Pusher, and congratulations on achieving your FIRE goals. Best of luck with whatever the next chapter holds.

You’ve done well to manage your own exit. There aren’t many long term contractors who can honestly claim to have departed at a time of their own choosing, rather than having the economic gods and the ever changing skillset trends choose for them.

I’ve experienced the rollercoaster ride through enough market cycles to know that my approach works while my niche skillset remains in demand, and the market is relatively buoyant. Eventually the music will stop and I will find myself without a chair. At that point “sophisticated lifestyle designer” simply becomes “dinosaur with dated skills who couldn’t seem to hold down a job“. Such is life!

weenie 17 January 2020

My friend who retired at 52 was an IT contractor and during the last 5 years of her working life, used to take off months (up to a year one time) in between jobs to travel and potter around her house and garden. Eventually, she just got fed up with work and figured she had enough to retire. Her youngest is still at university but when I met up with her recently, she had no concerns about running out of money. I did remind her however that she would have even more money if she didn’t use SJP as her broker…

{in·deed·a·bly} 17 January 2020 — Post author

Thanks weenie.

Sounds like your friend has the lifestyle design side of things figured out. Not so much the brokerage element however!