Brian pumped the brakes on the heavily loaded Bedford farm truck.

The pothole-ridden dirt track was steep.

His descent was alarmingly swift.

The intimidating closed steel gate at the bottom of the hill rapidly approached.

Brian downshifted gears. He felt the rear of the truck starting to drift, as the load on the back shifted alarmingly.

He swore, dislodging the lit cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth. It landed in the open packet of roll-your-own cigarette papers on his lap.

He swore again, and stood on the brakes. The wheels locked up, tyres skating across the red dirt as the truck’s momentum hurtled it towards the gate.

The draught from the open driver’s window fanned the burning cigarette embers, igniting the rest of the rollies.

Brian swore a third time, this time with feeling!

The old Bedford shuddered to a halt, half on half off the dusty track, less than a metre from the closed gate.

Brian knocked the engine into neutral and yanked on the parking brake with one hand. With the other, he frantically heaved the merry little blaze away from his slowly roasting gentlemen’s vegetables, and out the open window.

Then swore again as he leapt down from the cab, urgently stamping out the now smoking tufts of dead grass that his burning rollies had ignited. That is how bushfires get started!

Once the fire was out, Brian looked down at the scorch mark his desert boot now sported. In a torrent of cuss words that would have made a sailor blush, he trudged over and unlocked the gate.

The gate slowly swung open, revealing a slight incline on the other side.

Brian stalked back around the front of the truck and leaned in through the open driver’s door.

Knowing he would need to lock the gate again once the truck was through, Brian released the parking brake, intending for the old Bedford to roll through and come to a halt at the incline.

His plan almost worked.

The idling truck did roll forward… straight over both Brian’s desert boots, breaking both his feet!

He screamed and fell helplessly to the side of the road, landing next to the still warm patch of scorched grass.

Brian swore. He could really use a cigarette!

It would be a long wait before someone came searching for him along that remote dirt track.

Taking shortcuts

It is human nature to take shortcuts, to seek out the easy way forward.

Often times this impulse results in our scoring an own goal, as Brian did by running over his own feet while he attempted to avoid the effort of climbing in and out of his truck.

Yet no matter how many times this approach lets us down, the temptation to cut corners remains.

Recently I have been toying with the idea of adjusting my investment strategy to increase the amount of free cash flow my portfolio generates.

Under my seasonal working pattern the greater the free cash flow, the longer my periods of semi-retirement can be. That is a tempting outcome, motivating indeed!

A seemingly obvious answer would be to swap out a low-cost index tracker for a slightly higher cost “high yield” tracker.

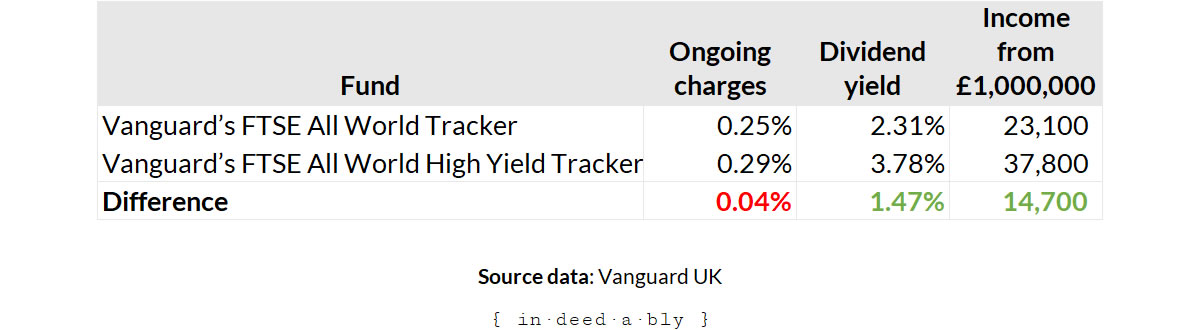

Consider the following example using two of Vanguard’s global tracker ETFs: VWRL and VHYL.

Making the change would increase the dividend stream by 1.43% a year. If you shifted a million pounds from one to the other you would receive an additional half a median UK household disposable income in your bank account.

Sounds simple, no? Except for the part about finding a spare million pounds!

what about capital growth?

But here is the thing.

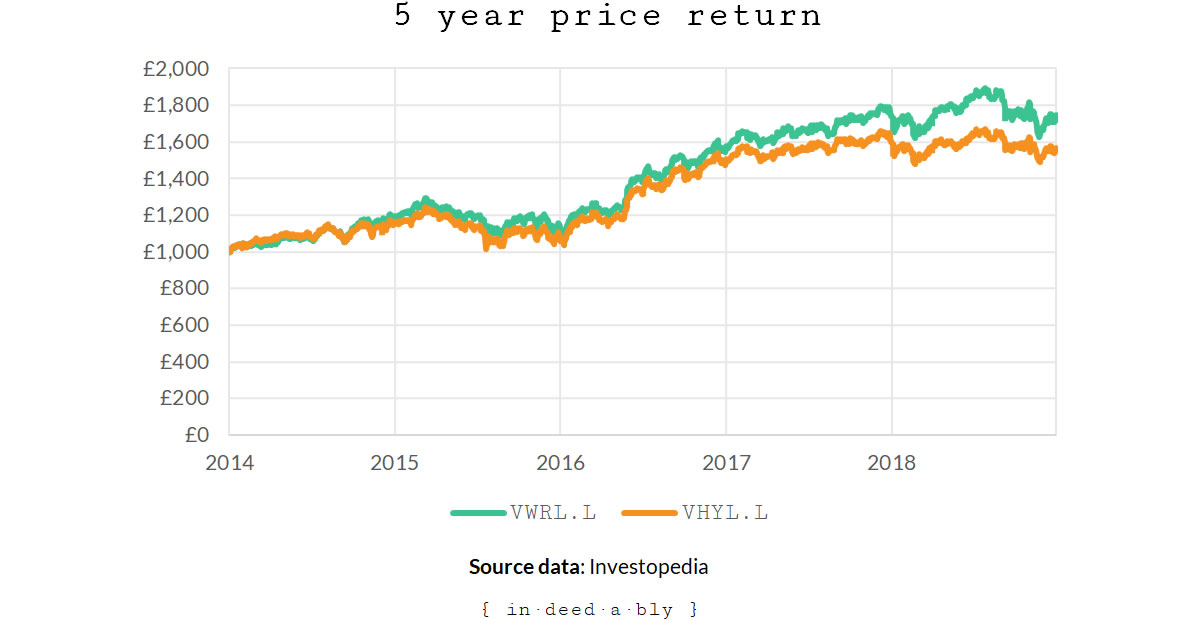

When I evaluated the price performance of the two ETFs I observed a material difference.

The higher-yielding fund underperformed the index tracker by 11% over the five year period for which data is available. This wasn’t a one-off surge at the end of the comparison period either, there was a constant underperformance throughout.

The good news is the higher dividend yield ETF did throw off more free cash flow, as I desired.

The bad news was the higher dividend yield came at a cost of materially less capital growth.

Dividends + Capital Growth = Total Return

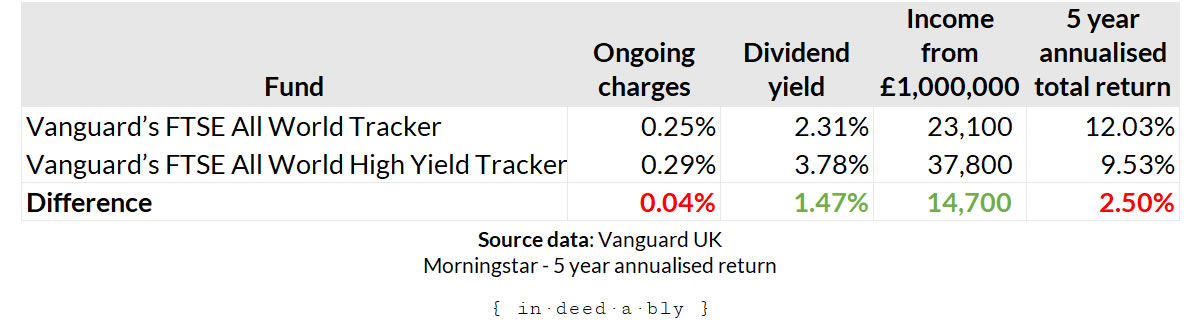

To work out whether this change in approach would do more harm than good, I looked at the annualised total returns for the two funds. A total return assumes that the all dividends and share buybacks are reinvested, encapsulating the entire return an investor would have received (before fees and taxes).

In this case the annualised total return of the index tracker was more than 26% greater than the high yield fund over the five year comparison period!

If I were to take this shortcut by reallocating my funds in pursuit of the higher dividend yield, I would be forgoing a significant amount of capital gains. The amount I would be left out of pocket would be the financial equivalent of Brian’s two broken feet!

Why the underperformance?

This got me thinking. Why did the index tracker outperform the high yield fund so convincingly?

There was the difference in ongoing charges, but this amounts to little more than rounding error.

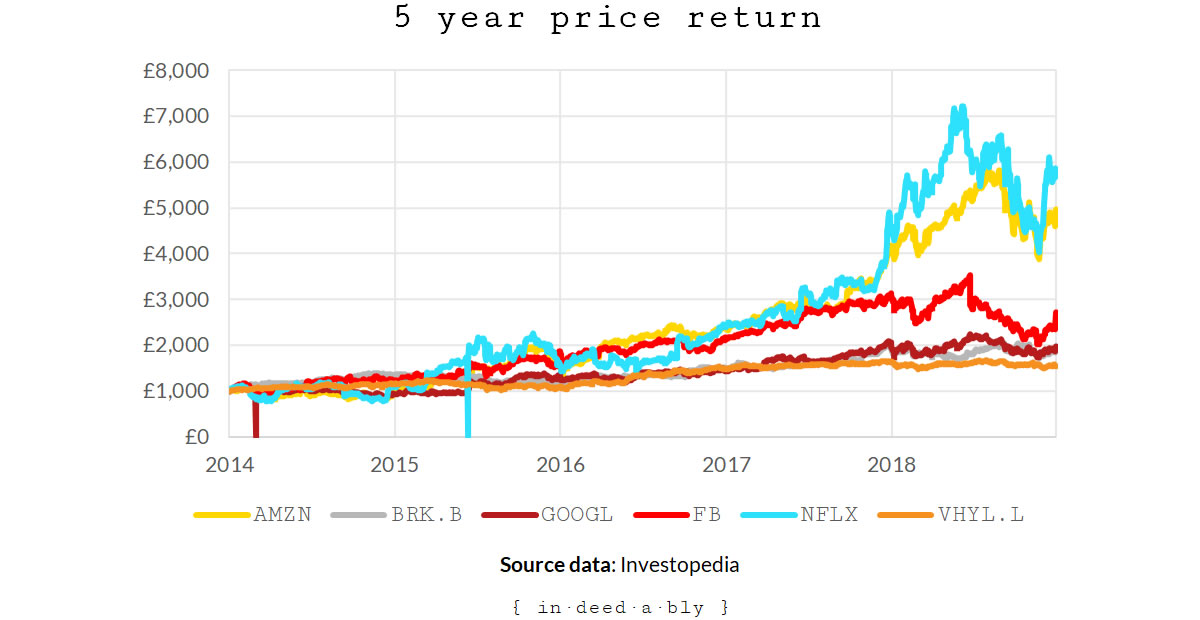

After skimming through the top 10 holdings of each fund, the answer leapt out at me: not all companies pay out dividends.

93 of 505 companies currently included in the S&P500 pay no dividends. Collectively these account for more than 19% of the index weightings.

The NASDAQ 100 has an even higher proportion of non-dividend payers, 49 out of 103 companies. In total they form more than 45% of the index weightings.

If I had switched to a dividend yield chasing strategy 5 years ago, I would never have enjoyed the rapid growth of innovative companies such as:

- Amazon

- Netflix

- Paypal

- Tesla

- … and Berkshire Hathaway.

The world according to Warren

Warren Buffett once shared his thoughts about dividends in the 2012 annual Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter. To paraphrase: companies only issue dividends when they have run out of value-generating ways to deploy capital.

In other words, the management believes that shareholders could do something more productive with the funds than the company could.

Buffett observed that a profitable company can allocate its earnings in the following 4 ways:

- Reinvest in itself

- Search for acquisitions

- Return capital via share buybacks

- Distribute dividends

Reinvesting profits

A company seeking to expand or develop new products can reinvest profits in its own business.

This is how small businesses grow into big businesses, via the funding of “projects to become more efficient, expand territorially, extend and improve product lines or to otherwise widen the economic moat separating the company from its competitors.”

Growth by acquisition

Companies may seek to expand via acquisition.

Perhaps they wish to vertically integrate, and gain more control of their supply chain or distribution channels.

Maybe they wish to reduce competition, acquire talent, or buy something rather than investing the time to build it themselves.

Share buybacks

A share buyback occurs when a company decides there is nothing productive it can do with its excess capital, so it returns it to shareholders.

This takes the form of the company repurchasing its own shares from shareholders, which reduces the number of shares issued, and increases the price of those remaining shares.

Over recent years buybacks have gained in popularity, as they are often more tax efficient than declaring dividends. In the United Kingdom, the capital gains tax rate is 20% for higher rate taxpayers on gains over £11,700.

Buffett observes that a buyback “is sensible for a company when its shares sell at a meaningful discount to conservatively calculated intrinsic value. Indeed, disciplined repurchases are the surest way to use funds intelligently: It’s hard to go wrong when you’re buying dollar bills for 80¢ or less.”

There is an often repeated conspiracy theory that greedy CEOs often execute share buybacks to boost the share price, thereby maximising the value of the stock options element of their performance-related remuneration package.

Whether there is any truth to this story probably depends on the individual company.

Dividends

Companies declare dividends to distribute profits they have no productive use for to shareholders.

Unlike buybacks, the number of shares on issue remains unchanged, so providing the overall value of the company remains unchanged, then so too does the share price.

A United Kingdom higher rate taxpayer will be charged 32.5% on dividend income over £2,000.

That is a 12.5% higher tax rate and kicks in £8,000 earlier than capital gains tax!

Hoarding or squandering

Buffett neglected to mention the all too common fifth option: the money can be stashed away, or squandered.

An example of the former is Apple’s USD$237 billion in cash.

Amazon’s adventures into mobile phones and takeaway food delivery, Tesco’s foray into consumer electronics manufacturing, or Superdrug’s decision to establish up a mobile phone network might all be viewed as examples of the latter.

What about “Dividend Aristocrats”?

There is a popular school of thought that suggests investing in “Dividend Aristocrats” stocks is the road to riches. Under this philosophy a company only becomes worthy if it meets the following criteria:

- Is included in the S&P500 index

- Has consistently paid out dividends for at least the last 25 years

- The size of those dividends have only ever increased

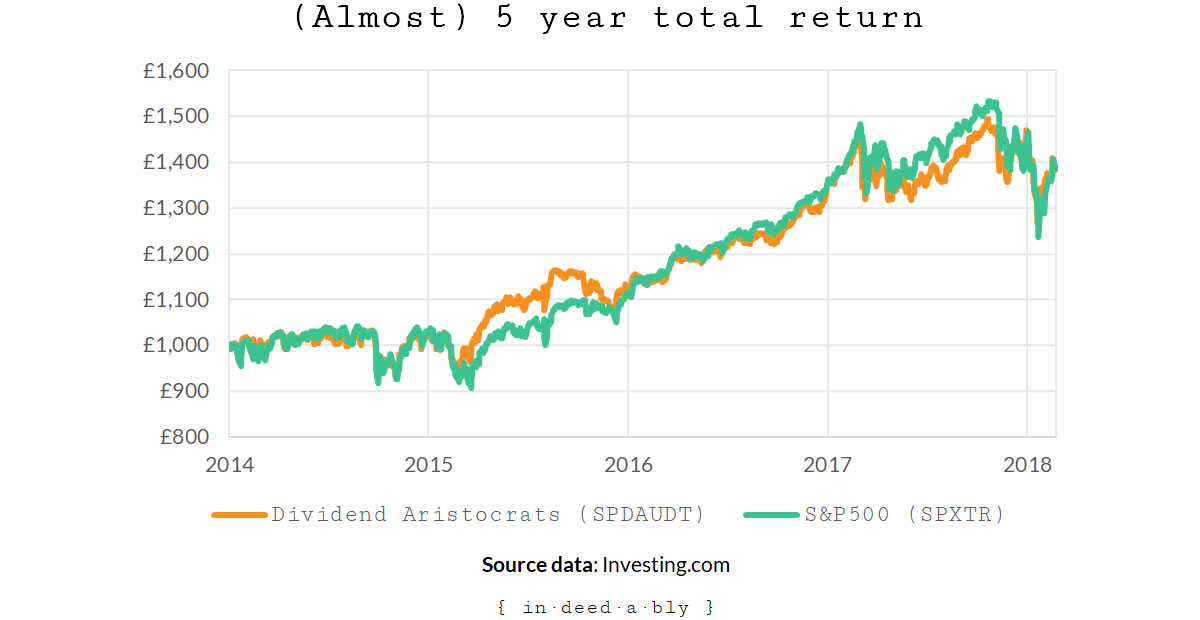

Sounds a tad self-limiting to me, but once again I compared the total returns of the Dividend Aristocrats index against that of the overall S&P500.

Unfortunately the total returns price history for the Dividend Aristocrats index is too limited to draw a definitive conclusion. Based upon the 4+ years worth of data that is available, the aristocrats enjoyed roughly the same total returns as the overall S&P500. What they missed out on in capital gains they made up for in dividend payments.

Should I take the shortcut?

Where does that leave my quest for increased free cash flows?

Attractive a shortcut though it may be, chasing dividend income at the expense of capital growth appears to be somewhat shortsighted.

This is akin to the real estate investor who buys “cheap” property in crappy locations in order to generate rental income. They fail to realise that however nice the rental income may be, it is the capital gains that typically makes property investors wealthy.

The conclusion I reached was that chasing dividends for cashflow alone was much like eating a late night kebab.

It may seem like a good idea at the time, but it is something I would likely come to regret later, when I realised that the opportunity cost of forgone capital growth outweighed the benefits of the free cash flow.

References

- Apple Inc. (2018), ‘Form 10-K’, United States Securities and Exchange Commission

- Buffett, W. (2013), ‘Berkshire Hathaway Inc Shareholder Letter’, Berkshire Hathaway

- IndexArb (2019), ‘Dividend Yield for Stocks in the Nasdaq 100‘

- Investing.com (2019), ‘S&P 500 Dividends Aristocrats Total Return (SPDAUDT)‘

- Investing.com (2019), ‘S&P 500 TR (SPXTR)‘

- Investopedia (2019), ‘Price history API‘

- Girouard, J. (2018), ‘Are Corporate Buybacks Basically Just Insider Trading? (And Other Questions You’re Afraid To Ask)’, Forbes

- Gov.uk (2019), ‘Capital Gains Tax rates and allowances‘

- Gov.uk (2019), ‘Income Tax rates and Personal Allowances‘

- Gov.uk (2019), ‘Tax on dividends‘

- Gov.uk (2019), ‘Tax when you sell shares‘

- Morningstar (2019), ‘Vanguard FTSE All-World High Dividend Yield UCITS ETF (GBP)‘

- Morningstar (2019), ‘Vanguard FTSE All-World UCITS ETF (GBP)‘

- Office of National Statistics (2018), ‘Household disposable income and inequality in the UK: financial year ending 2017‘

- Pak, E. (2011), ‘Is That Fund as Good as It Looks?’, Morningstar

- Rawson, M. (2012), ‘Why Does My ETF Dividend Fluctuate So Much?’, Morningstar

- Slickcharts (2019), ‘Nasdaq 100 Companies‘

- Slickcharts (2019), ‘S&P 500 Companies by Weight‘

- Sure Dividend (2019), ‘2019 List of All S&P 500 Stocks & Companies‘

- Vanguard (2019), ‘FTSE All-World High Dividend Yield UCITS ETF (USD) Distributing (VHYL)‘

- Vanguard (2019), ‘FTSE All-World UCITS ETF (USD) Distributing (VWRL)‘

Caveman 8 February 2019

Man, that first bit read like one of those training videos from the 90s where they show you all of the things that can go wrong if you don’t follow the rules!

In terms of you point about the High Yield fund vs the index tracker. That’s true (although I would be interested in seeing a longer data set). But are you asking quite the right question?

From what I can tell you’re still the in accumulation/growth phase rather than a drawdown phase – your winter earnings cover you expenses for the year for now don’t they? If I’m right what’s your thinking in wanting to get more free cash right now?.

When you come to drawdown/decumulate I think that your figures suggest you stay in the tracker but, in addition to the dividends, sell some of the units to add to your income. The challenge here is possibly a psychological one that many face (including me) – having spent so many years saving it feels wrong to sell. In that case the High Yield option may be a compromise that works for your peace of mind (even if the numbers suggest you do otherwise).

{in·deed·a·bly} 8 February 2019 — Post author

Thanks Caveman, you mount a fair challenge.

I must admit I’ve never been a huge fan of the acquisition/preservation/decumulation phases commonly espoused by financial planners, as they contain an implicit assumption that the punter chooses to follow a standard linear life script.

That assumption is a poor fit for a surprising number of people. For example:

In my case passive income streams already sustainably cover my family’s basic cost of living (e.g. housing, food, utility bills, clothing).

However they don’t yet sustainably cover my total lifestyle costs (e.g. holidays, hobbies, etc). It is quality of life enhancing things that my winter working hibernations finance currently.

I could potentially sell some assets to deleverage, reduce investing expenses, and lower my tax bill. That wouldn’t get me all the way there, but it wouldn’t be far away from it.

My approach differs to many in the Financial Independence community, in that I have no desire to gradually sell off my portfolio to fund my lifestyle. There are a few reasons for this:

There will come a time for changing gears and chasing income, once my portfolio is large enough for those income streams to comfortably sustain me. However doing so too early would likely see me crying beside the road like poor old Brian, as the capital gains truck rolls off down the hill without him!

FIRE v London 8 February 2019

Very good post which touches on a common dilemma in the world of portfolio allocation.

Minor factual correction: capital gains tax is only 20pc for higher rate tax payers, except for real estate holdings. Yet another reason to prefer equities to buy-to-let!

{in·deed·a·bly} 9 February 2019 — Post author

Thanks FvL. Correction applied.

I’ll give my fact checker a slap upside the head for dereliction of duty… [ouch]!

weenie 11 February 2019

“buys “cheap” property in crappy locations in order to generate rental income. They fail to realise that however nice the rental income may be, it is the capital gains that typically makes property investors wealthy.”

Hah, this could be a sweeping comment for people who buy in the north of England where rental yield totally trumps capital gains, however I’d say most of us know what we’re getting into! 🙂 It depends on what you consider more important, sustained high rental yield and low capital gains or low yield but high capital gains. It also depends on how the property investors funded their properties – if highly leveraged, the current changes in tax legislation will have hit them hard so they could be forced to sell in a depressed market. What happens if house prices plummet and there’s negative equity?

I think it’s just about preference in the end regarding capital growth or income – I hold a mixture of both, including both VWRL and VHYL, although a lot more in the former. I’ve ramped up my investments which pay higher dividends in the last couple of years, only because I intend for the income to cover some of my living expenses when I no longer work. I wanted to see the actual income coming in as I didn’t want to go for growth and switch to income later, only for that income not to meet my expectations. As Caveman mentions, it will be psychologically harder for me to sell capital to get income, even though I know I’m going to have to do it. I intend to spend my accumulated wealth.

{in·deed·a·bly} 11 February 2019 — Post author

Thanks weenie.

That is an interesting observation about the north of England. For mine it comes down to opportunity cost. If an investor is forgoing £50k in capital growth in order to generate £15k in cash flow over the same elapsed time period, then they have made a suboptimal asset allocation decision.

Of course the inverse is equally true.

This is why running the numbers using total returns is so important, it is very easy to be tempted by the accessible free cash flow when the truth may be that “free” is actually very expensive!

I think the right answer is to match up time scales with cash flow needs, so that we can leave as much positioned for the optimal total return as practicable, while still generating enough income to lead our desired lifestyle.

HK Expat 14 February 2019

Interesting comparison.

I hold VHYL rather than VWRL not just for the yield, but also for the underlying share make up. VHYL is normally around 35% US shares, compared with VWRL at around 52%. With the US having outperformed the rest of the world for the last 10 years and being at a substantially higher p/e the chance of reversion to the mean makes me believe that longer term the outperformance of VWRL will unwind- and so I view VHYL as lower risk of capital loss longer term. Each to their own…

Of course as you point out VHYL has no amazon, apple, facebook, google etc but I address that in part by holding Manchester and London IT. It is heavily tech focussed with heavy weightings in those companies.

{in·deed·a·bly} 14 February 2019 — Post author

Thanks for sharing your thoughts HK Expat.

When used for the right purpose, as part of a considered asset allocation decision, they can both be effective investment vehicles to hopefully help attain your goals.

My main point was to consider total return rather than chasing yield alone, and it sounds like you are doing that while minimising your down side.