Harold was an artist. It was all he had ever wanted to be.

He stayed true to his dream, completing one of those fine arts degrees that are widely dismissed as a waste of time and a massive financial own goal.

Painting landscapes was Harold’s gift. His ability to record on canvas the light and essence of a place captured the hearts and wallets of many art lovers.

As hobby became a career, he proved the doubters wrong by living his dream.

At age 24 Harold did something completely different to anything he had attempted before.

He designed a flag.

A simple black stripe over a red stripe, with a yellow circle in the centre.

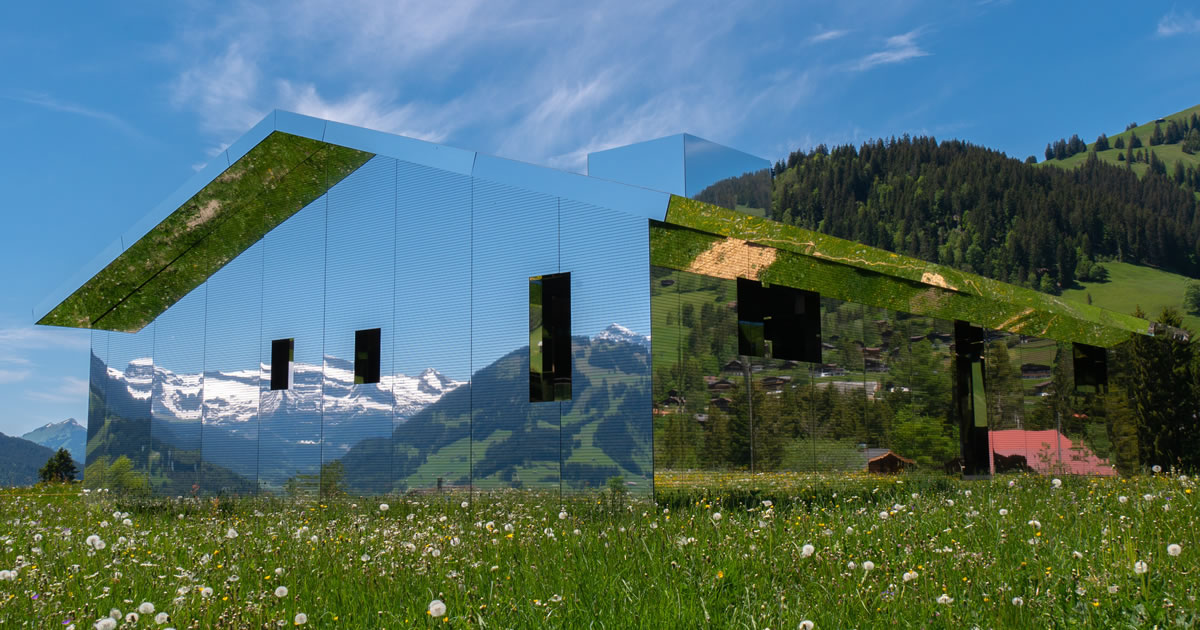

Harold’s flag was adopted by the indigenous people of Australia, and proudly flown above their “tent embassy” permanent protest site on the lawns opposite the Australian Parliament.

24 years later, the Australian government formally recognised Harold’s design as an alternative national flag. Parliament may have relocated, but the flag resolutely flies over the tent embassy to this day.

Normally flags are designed on behalf of a government, which means the government controls the usage rights. In this case, Harold designed the flag as an individual, and it was subsequently adopted by a nation.

Due to this intriguing legal quirk, Harold retains ownership of the copyright to his design. He had to go to court to secure those intellectual property rights, but the court ruled in his favour.

In practice, this means that every single usage of the design must first be approved by Harold.

Harold would be within his rights to charge licensing fees to anyone wanting to use his design.

Think about that for a second. Substitute Harold’s flag for the Union Jack or the Stars and Stripes to get an appreciation of the magnitude of his intellectual property rights.

Harold intended the flag to be “a strong and unifying symbol for Aboriginal rights and justice”. He allowed it to be freely used by education, healthcare, government and not-for-profit organisations where their work benefitted Australia’s indigenous peoples.

Everyone else was supposed to pay him a licensing fee to use the design.

Few did.

Nothing happened to them. The burden of enforcement falls to the property rights owner.

At this point, it is worth noting that Australian copyright law does not support the concept of “fair use”.

With few exceptions, a copyright holder can seek damages from anyone reproducing their intellectual property in part or in full without consent. This means actions like posting film clips, quoting text, sampling music, taking photos, or wearing a tattoo potentially violates copyright.

A young girl once won a competition to design the Google logo for a day. Her drawing featured Harold’s flag behind several cute iconic Australian animals. Google sought Harold’s consent to display his flag so that the winning design could be proudly displayed on the Google home page.

Neither Google, nor the young girl with dreams of sharing her art with the world, qualified for a copyright exception. Those are reserved for critics criticising, lawyers litigating, reporters reporting, students studying, comedians satirising or parodying, and governments doing whatever they like.

24 years later the benign neglect of Harold’s property rights came to an abrupt end. Now an old man, he sold the exclusive global image rights for his design to a litigiously minded third party.

Gone were the days of unenforced property rights. The new license holder flexed their legal muscles.

Cease and desist orders threatening legal damages were fired off to everyone ranging from professional football teams featuring the flag on their uniforms to souvenir shops selling artworks by indigenous artists.

Aboriginal “tent” embassy. Image credit: Pixabay.

Legalised extortion

Harold’s story reminded me of a time long ago when I was served with a similar legal notice. The 150+ page document of dense legalese could be summarised as follows:

“To whom it may concern:

You may have used something that we believe we own.

You didn’t ask our permission first, and that hurt our feelings.

We imagine that your unauthorised usage has injured us immensely.

Cease and desist immediately.

We demand damages sufficient to pay off the national debt of a small banana republic.

Refuse to pay and we will take you to court.

We will drag proceedings out until you are bankrupted by the legal costs of defending yourself.

We have more money than you, so can afford to outlast you.

Menacingly yours,

Very expensive lawyer at large patent trolling law firm

P.S. My time is billed at £1000 per hour

P.P.S. It does not matter who is right, that is not how the legal system works. Pay up. Now.”

I was shocked.

Outraged.

Scared.

Over the course of the following week, I met with a series of lawyers who specialised in intellectual property disputes. All those discussions followed a similar pattern.

The lawyer would skim through the weighty document and ask a few questions.

“What do you think?” I would demand.

“You have done absolutely nothing wrong” they would reply.

“So what do I do next?” I would ask.

“Pay them” they would advise.

“What! Why?” I would protest.

The lawyer would give a resigned sigh. Then they would provide an explanation along the lines of the following, using the tone of voice you might use to try and explain quantum physics to a toddler:

“Because you can’t afford to defend the matter in court.

There is no guarantee you will win.

Lose and you have to pay damages, and possibly the other side’s legal fees. Their lawyers are VERY expensive and very good at exactly this kind of shakedown.

A win may be a Pyrrhic victory. There is no guarantee the other side would be required to pay your legal costs, which would be in the region of £10,000 per day.

So you pay them off. Chalk it up to experience. Get on with your life.”

The first couple of times I heard this message I protested at how unfair that was. The lawyers would give me an apologetic shrug.

The fifth time I heard it was from a family friend, who happened to be a senior lawyer. She observed that the legal system had been weaponised. Justice is only available to those who can afford it.

She noted that already the cost of shopping around for lawyers was consuming time and money I would otherwise have devoted to servicing my own paying clients. The longer and harder I fought, the greater that cost would be.

A simple cost-benefit analysis showed settling the lawsuit was the logical answer.

Fighting back

Bullying and extortion offend my sensibilities. My instinctive reaction in such circumstances has always been to hit back hard. And win. No hesitation. No holding back.

In my experience bullies are cowards. When faced with unexpected resistance, most times they slink off in search of easier prey. Occasionally they give you the mother of all ass kickings.

A lawsuit brought by a faceless legal entity asserting property rights is difficult to stand up to. Legal responses incur vast fees. The lawyers make money win, lose, or draw.

Alternative responses are… less legal.

Behind every faceless entity is a person making decisions. Everyone has pressure points.

Vulnerabilities.

Weaknesses.

It is often said that sometimes the way to win is to play the man, not the ball. Other times it is better to change the premise, and simply play not to lose. Occasionally it is best to not play the game at all.

A frank conversation with the man behind the curtain resulted in the threat being swiftly withdrawn and a negotiated settlement. The lawyers had been right about one thing, defending yourself is expensive.

It is unlikely those facing damages claims for using Harold’s design will get off so lightly.

ownership

That got me thinking about ownership and property rights. Things aren’t what they seem.

My son’s year seven science textbook states that something is alive if it can perform a discrete set of functions: movement, respiration, sensitivity, growth, reproduction, excretion and nutrition.

Every day billions of living things, ranging from tiny single-cell amoeba to enormous blue whales, happily perform these functions without giving a passing thought to ownership or property rights.

When something looks like food, catch and eat it. If something sees you as food, fight or run away.

Some creatures piss on trees or put up walls to mark out their territory. The sense of ownership is fleeting, more perception than reality.

At some point, a stronger creature will inevitably come along and take that territory from them, just as they claimed it from whomever owned it previously.

Over time, humans have attempted to impose rules and order over what can be owned and how that ownership can be transferred. A multitude of inconsistent belief systems, customs, laws, and rules govern the behaviour of those who choose to be bound by them.

To survive we each have basic needs that must be met: Clean air. Water. Food. Warmth. Shelter.

Air

The air we breath is freely available to all, and not owned by any one person.

Yet we have taken something we don’t own, and granted governments the power to sell off the right to pollute it, injuring our health and literally taking years off our lives in the process.

Water and warmth

Water is freely available to most. Aquifers, rivers and lakes naturally replenish without human involvement.

In cities, we pay for the convenience of having drinkable water on tap.

This typically takes the form of a subscription model, where we pay for access to a supply network for a commodity product.

Usage may be metered on a pay-per-use basis, as with other utilities such as bandwidth, gas, electricity, and sewerage. However, it is impossible to identify exactly which litre or megabyte or kilowatt we purchased.

This creates a situation where we never actually owned the thing we are paying for.

Before we consumed the commodity it belonged to the utility provider.

After we consumed the commodity it is gone, leaving us with a bill.

Years ago I saw an interview with the CEO of a bottled water company. He made the surprising statement that he wasn’t in the water business, he was in the bottle business.

The water was a commodity, indistinguishable from any other water source.

He was selling a brand.

An image.

The illusion of control.

A perception of health benefits associated with sealed bottled water.

Food

Food is more complicated.

Sometimes we can freely take what we find. Blackberries beside the Thames path. Pick them and the worst that may happen is an upset stomach from the weed killer they have been sprayed with.

In other circumstances, this same action would break all manner of property ownership rules. Spit-roasting that deer found in Richmond Park is generally frowned upon.

Poaching.

Cruelty to animals.

When we grow food or purchase it from the supermarket, we are acquiring ownership of a good.

However, when we purchase a meal at a restaurant we are buying a service.

The chef sourcing ingredients and preparing the food. The waiter serving it to us. The dishwasher who cleans up afterwards.

The price of the food is inseparable from the service elements required to enjoy it.

Similar to the utility example above, before we order the meal doesn’t exist. While we are eating, we briefly own the food on our plate. Once the meal is concluded we have a full belly and the bill.

Shelter

Housing in the United Kingdom is a mess.

When a person buys a freehold property, they assume ownership of the land and buildings upon it.

By contrast, when a person buys a leasehold property, what they are really buying is the right to occupy land that they do not own, for a finite period.

This makes them tenants, who make periodic ground rent payments to the actual owner, the freeholder.

If the leaseholder repeatedly violates their lease agreement, the freeholder can kick them out. For example advertising their flat on Airbnb when the building rules prohibit short term tenancies.

When the lease expires, the freeholder can kick them out.

The 16% of homeowners occupying leasehold properties aren’t really home owners at all.

Leasehold – the illusion of home ownership. Image credit: Heidelbergerin.

Of course ownership of a freehold property can also be taken away, via Compulsory Purchase Orders or eminent domain claims. There is always someone tougher and meaner waiting in the wings!

Property owners don’t own their view. Today’s harbour views could tomorrow be looking at the back of a new waterfront apartment tower.

Nor do property owners own their light. A neighbour is within their rights to build an extension or plant a tree that blocks out the sun or casts a big shadow.

Property owners don’t own some mineral rights below their land, nor the airspace above it. It sucks to be them when frackers or airport flight paths take a shine to their neighbourhood

Ideas

The ownership of ideas is fascinating to explore.

Nils Bohlin invented the seatbelt in cars. He gave it away for free to save lives.

Richard Ashcroft wrote “Bittersweet Symphony”, yet never made a penny from his iconic song. He had sought, and been granted, permission to sample an old Rolling Stones tune. A subsequent dispute saw all credit and royalties from the song’s success go to the Rolling Stones.

The band “Men at Work” borrowed just two bars of music from a 70-year-old folk song written by a long-dead school teacher. 27 years after they released one of Australia’s most recognisable songs, the band was successfully sued for 60% of the cumulative royalties the song had earned.

Marvin Gaye’s litigious offspring even managed to win millions in a lawsuit by laying claim to ownership of “that late 70s feeling”.

Not a sequence of notes or a tune.

Not specific lyrics.

A feeling!

The CSIRO earned over £200 million in royalties from its invention of Wifi, after asserting their intellectual property rights in court.

Wave the flag

Flags can be waved in triumph or surrender. They can signal danger or mark the finishing line.

It will be fascinating to watch how the story of Harold’s flag plays out.

The legal rights that protected the CSIRO’s invention also screwed Richard Ashcroft.

The ownership of an idea that fattened the Gaye children’s wallets, nearly emptied mine.

They have been used to delay progress, prolong suffering, and suppress competition.

Traditional car manufacturers bought up early electric car firms just to close them down.

Pharmaceutical companies generate huge returns from keeping drug prices high to the detriment of patients and health systems everywhere.

Imagine how different the world would be had Tim Berners-Lee followed their lead, and sought to milk his invention of the internet for all it was worth, rather than giving it away for free?

Harold’s simple design, something that can be drawn by hand in less than 15 seconds, has the potential to make somebody very wealthy indeed.

Unfortunately that somebody is unlikely to be Harold.

References

- Alexander, I. (2019), ‘Explainer: our copyright laws and the Australian Aboriginal flag’, The Conversation

- Allam, L. (2019), ‘Government could buy Aboriginal flag copyright to settle dispute, lawyer says’, The Guardian

- Allam, L. (2019), ‘Ken Wyatt ‘hopeful’ of resolving Aboriginal flag copyright dispute’, The Guardian

- Australian Copyright Council (2017), ‘Fair Dealing: What Can I Use Without Permission‘

- Australian Copyright Council (1997), ‘Thomas v Brown & Tennant [1997] 215 FCA (9 April 1997)‘

- BBC (2019), ‘Life processes’, BBC Bitesize

- Beaumont-Thomas, B. (2019), ‘Bittersweet no more: Rolling Stones pass Verve royalties to Richard Ashcroft’, The Guardian

- Carrington, D. (2018), ‘Air pollution cuts two years off global average lifespan, says study’, The Guardian

- Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire (2013), ‘The birth of the Web’, CERN

- Croft, J. and Fortado, L. (2016), ‘Top London lawyers charge £1,000 an hour, study finds’, Financial Times

- Department for Communities and Local Government (2004), ‘Compulsory Purchase and Compensation‘

- Gabbatt, A. (2010), ‘Men at Work stole Down Under riff from Guides’, The Guardian

- Gov.uk (2019), ‘Extending, changing or ending a lease‘

- IP Australia (2016), ‘CSIRO’s WLAN patent‘

- Minerals UK (2017), ‘Legislation & policy: mineral ownership‘

- Moses, A. (2010), ‘Oh dear: Google flagged over logo dispute’, Sydney Morning Herald

- O’Grady, S. (2009), ‘The man who saved a million lives: Nils Bohlin – inventor of the seatbelt’, The Independent

- Office of National Statistics (2017), ‘Families and Households: 2017‘

- Pasick, A. (2015), ‘A copyright victory for Marvin Gaye’s family is terrible for the future of music’, Quartz

- Roberts, A. and McFaul, S. (2019), ‘What is a leasehold?’, MoneySavingExpert

- Taylor, J. (2019), ‘Heathrow third runway: See how proposed flight paths will affect where you live’, Evening Standard

- Thomas, H. (2018), ‘The Artist‘

- University of Chicago (2019), ‘The Air Quality Life Index‘

- Vaughn, A. (2019), ‘UK fracking industry pushes for review of earthquake limits’, The Guardian

- Wilson, W. and Barton, C. (2019), ‘Briefing paper Number 8047: Leasehold and commonhold reform’, House of Commons Library

GentlemansFamilyFinances 21 June 2019

One thing that i noticed a few years back was that copyright laws for music were extended from 50 to 70 years. The main people benefiting were the record companies and aged muscians.

Sadly, there are still some bands from the 60s who are touring and that seems to be because they were screwed over back in the day.

This extension doesn’t help them at all which is a bit sad really.

{in·deed·a·bly} 21 June 2019 — Post author

Thanks GFF.

I must confess I’m conflicted about the whole ownership of ideas thing.

I think it is disgraceful when people work hard producing something of value, and then somebody else steals that work product and makes money from it. For example every time Monevator hits publish on an article, some thieving troll copies and pastes his words on their own monetised site.

On the other hand, I would be horrified if somebody cured cancer, then held the world to ransom for access to their life changing discovery. Imagine if Alexander Fleming had decided to charge £10,000 a dose for penicillin back when he discovered it.

In the workplace I have often seen universities, employers and clients lay claim to the intellectual property produced by folks working for/with/near them. Many contracts make it explicit that this will happen. This is fair enough if the discovery occurred on the employer’s coin, but is scandalous if the employee or student came up with it in their own time and got screwed out of their idea by an onerous contract.

I have a lot of respect for people like Berners-Lee and Bohlin. I fear the reason they are so noteworthy is because their selfless actions are so rare.

GentlemansFamilyFinances 21 June 2019

it’s a double edged sword isn’t it.

I’m lucky no one has thieved my posts! 🙂

Phil Money Mongoose 21 June 2019

I think with reasonable timelines for the government granted monopoly it is fine. However, the rules keep changing, copyrights are being extended and in certain areas, the industry is competitive enough that the long monopolies hinder competition rather than help it. It’s a complex web to unpick and too many vested interests to make the necessary changes.

{in·deed·a·bly} 21 June 2019 — Post author

Thanks Phil.

The tricky question is how long is reasonable?

A finite period?

The creator’s life time? With life expectancy of ~80 years, and some folks making it to nearer 120, that could be a very long time indeed.

What if they had invented the wheel, or writing, or the smallpox vaccine when they were 20 then got greedy about it or sought to stifle innovation and competition?

Then the flip side is if the exclusivity period were too short, would pharma companies and the like achieve the return on investment required to bother investing in drug treatments and cures. Open source is great for software development, but the model may not translate quite so well to medical research.

How long should Matt Groening or Mick Jagger or Stan Lee be protected, before having to watch other people making megabucks from their creations?

The other question is, are these questions all moot when inconsistent laws mean the concept of copyright or intellectual property rights don’t exist at all in some locales?

If I want to draw a Mickey Mouse cartoon then I either have to ask permission or wait until the character becomes public domain in 2024.

Or I can it now in a jurisdiction where copyright isn’t recognised.

It is a fascinating issue.

ermine 21 June 2019

The Americans got it about right with the original patent term of 14 years IMO. Particularly in the faster moving world of development now, that’s enough both as an incentive to get it out there and in the world, and short enough to avoid being a dead hand on progress.

Even for copyright i can’t see any justification for more than 40 years, a typical working life. Any more is greed IMO, and the work of Disney’s lawyers 🙁

{in·deed·a·bly} 21 June 2019 — Post author

Thanks ermine.

For copyrightable endeavours I’d argue the lifetime of the creator is fair. JK Rowling should be able to control what happens to her Harry Potter characters while she is alive. Once she is dead they are no longer her problem, and should pass into the public domain.

Patents I think you’re probably right.

[HCF] 21 June 2019

I am a true believer of the open-source philosophy and in my opinion everyone should make the world a better place as much as one is able to do so. Like the aforementioned gentleman and many other folks with good intentions all over the globe.

The equation gets more complicated when money gets added. I am not really educated in this field but I think copyright should be the inalienable right of the inventor/creator. Maybe I would even restrict selling those rights. Inheritance is also questionable but understandable. Still, I honestly think while the inventor/creator should own the rights abusing or taking an unfair advantage of it should be prohibited and should result in losing the right itself.

I get the point of the authors but all this huge copyrighting and patenting industry disgust me. I think they are fighting the wrong fight. I am always happy to see when authors giving away their “products” free and focus on building a business model which builds on top of it.

For an example there is a Hungarian blogger who is an extremely smart financial expert, educator, and adviser. He made a course which you can attend for money. He also made the 25 hours of the recorded video freely available with adding a disclaimer to the start that he wanted to prevent this whole circus about copyright and he published it himself so people don’t have to bother with stealing it. He states that if you watch it and you feel it useful you can give a donation to his organization.

Publishing their music for free is also a respectable act from any band (not sure about using it though). I pretty much like the attitude of these guys to the topic 😉

{in·deed·a·bly} 21 June 2019 — Post author

Thanks for sharing that fun song HCF, it is funny because it is so true!

The intentions question is an interesting one also. What if you were like Enrico Fermi, who came up with some clever ideas that were then applied to create something horrible like a nuclear bomb? Should the inventor be able to control where and when their ideas are applied?

The same laws that would protect the control to the creator of Mickey Mouse could be used to prevent the widespread usage of solar cells for example.

I think this is why it falls to the choice of the individual. Kiszamolo and Linus Torvalds generously give away their work product. Harold and the Gaye children jealously restricted the usage of theirs.

Perhaps the law should include an eminent domain provision for intellectual property, that could only be applied where there was a demonstrable public benefit and where the rights owner refused to license or share their creation for a reasonable price.

[HCF] 21 June 2019

The case of Fermi is interesting, the nuclear power provides a great benefit these days but thinking about the nuclear explosions and especially with the very vivid memories of the Chernobyl series I think that it would have been better if he never had those clever ideas.

Still, most scientists are reasonable and know the dangers exactly. At least I would like to believe in this. Thus, yeah, they should control how and where should their ideas being put into use. On the other hand, I don’t think that any legal patents would prevent military to use them for their purposes…

Also, I really think that we should make a distinction between art/design things and scientific stuff. Not being able to use a Rolling Stones soundtrack or a photo of [insert any famous photographer] probably would not result in any deaths or missed enormous benefits.

What would I expect from such a law? That such things like the electric drive shouldn’t have been kept in the basement because of money reasons. That such things like keeping a potential cure for the alzheimer in secret could not happen. That bastards like Martin Shkreli would have been turned down at the first attempt when he skyrocketed the price of lifesaving medicine. Also, in an ideal world a company, like Monsanto should not be able to claim copyright on the corn molecules and prevent farmers from collecting seeds for the next season… Should I go on? 😀

{in·deed·a·bly} 22 June 2019 — Post author

I’d challenge whether scientists do know the dangers exactly. It is unlikely Rosalind Franklin would have foreseen that her discoveries would have ultimately led to DNA, cloning, designer babies and genetically engineered bio-weapons. However without her work, none of those would have been possible.

I agree the more practical the creation the shorter the exclusivity period, but as anyone who has studied the “dismal science” of Economics learned in their first lecture, the divide between art and science is both arbitrary and subjective.

weenie 10 July 2019

Ashcroft recently regained the rights to his song.

{in·deed·a·bly} 10 July 2019 — Post author

That is true weenie. It must have been a long 20 years while he watched others get rich off his creative works though.

weenie 10 July 2019

20 years too long IMO.