Britain. A dangerous and exotic land mysteriously located across the ocean on the edge of the world.

That is how Julius Caesar perceived it 2000 years ago, while his Roman legion was conquering Gaul.

The Gauls didn’t much like the idea of being conquered. They fought back, with some help from British allies.

The Romans won.

Gaul became part of the empire.

Caesar’s attention moved to across the British Channel.

The following year Caesar invaded. After a couple of attempts, a puppet king was appointed and tributes agreed.

Deciding Britain’s cold wet miserable winters weren’t much fun, the Romans packed up and returned home.

A hundred years passed.

Londinium

In Rome, a mad demagog named Caligula was now the emperor. He had wrestled much of the political power from the Senate, slept with his sisters, and appointed his horse to the priesthood.

The Senators didn’t think much of this. In a political tradition as old as time, they stabbed him in the back.

Any record of the horse’s theological insights has been lost over time.

An unlikely candidate named Claudius was thrust upon the throne.

Nobody much liked him. He was viewed as the least worst compromise.

Controllable.

Pliant.

Weak.

In need of a quick win to firm up a shaky power base, Claudius followed another ancient political tradition. He promised a swift decisive military victory and invaded a weaker foe: Britain.

The southeast of what we refer to today as England was quickly (re)conquered.

It took a generation to subdue the residents of what we now call Wales.

The Romans argued with the occupants of what is now Scotland for 80 years and got nowhere. Eventually, the Romans gave up and built a wall to keep them out.

On discovering a likely spot to cross the river Thames, the Romans built a bridge and established the settlement of Londinium.

Londinium prospered for 20 years, until Queen Boudicca burned it to the ground in protest over Roman plans to annex her kingdom into the empire.

That didn’t end well. There is a reason you don’t hear about the descendants of Boudicca and her Iceni people.

The Romans started over. Soon Londinium was a thriving centre of commerce and trade. To address the defensive weaknesses of the past, they constructed a formidable stone wall around the town.

350 years later things started to go south.

Fall of the Roman empire

The Roman empire had grown too big and costly to administer effectively.

The Eastern half of the empire was spun off. Smaller, leaner, and saddled with less accumulated technical debt than its lumbering former parent, the Byzantine empire thrived for a thousand years.

Meanwhile, the remaining Western half of the Roman empire struggled.

Their economic system was built on low-cost slave labour, fuelled by constant conquest and subjugation.

The once feared Roman legion had largely been outsourced to lowest-cost mercenaries. Fearsome and talented, but only as loyal as their next pay.

Endemic corruption and expensive military operations had emptied the government’s coffers, resulting in high taxation and rampant inflation.

Income inequality led to instability and insurrection.

The empire was hollowed out from within, leaving a brittle shell that was vulnerable to external attack.

And attack they did.

Being located on the “edge of the world” meant the Roman forces in Britain were at the end of a lengthy and vulnerable supply line. As the empire’s troubles grew, logistics became less reliable.

Eventually, the flow stopped altogether.

With no pay, supplies or prospect of reinforcements, the Romans in Britain abandoned Londinium.

Some went home.

The rest went native.

Lundenwic

At some point, the Saxons settled around the outside of the of Londinium’s abandoned walls. They established a town called Lundenwic.

A couple more centuries passed.

Lundenwic grew to become the largest town in Britain. Prosperity attracted the interest of Danish Vikings seeking plunder.

The Danes raided and pillaged Lundenwic. A decade later they returned to burn it down.

For 150 years, ownership of Lundenwic alternated between Danish Vikings and Saxons. Sometimes control was gained in battle, other times by inheritance.

Lundenburh

At some point, the Saxon king Alfred the Great decided to relocate from Lundenwic back inside Londinium’s far more defensible Roman walls. The town was renamed Lundenburh.

All that flip-flopping and uncertainty over ownership came to an end when William the Conqueror invaded. The Normans surrounded Lundenburh, cutting off supply lines and hopes of reinforcement.

Ever a city of traders with an eye for the best deal, the leaders of Lundenburh haggled.

In return for surrendering the city without a fight, William granted the London Charter of Liberties, changing Lundenburh’s name once more.

The Charter was unique at the time. London was free from the obligations, taxes and whims of local nobles or the church. The ability to self govern and set its own taxes provided a massive competitive advantage.

In practice, London’s inhabitants answered only to the crown. Sometimes, not even the crown.

London

Since that time London’s interests haven’t always aligned with those of the Crown and the Kingdom.

Nearly 600 years after the Charter was issued, the King requested London extend its special privileges to the surrounding suburbs and towns that had formed to support its thriving economy.

The City of London responded with the “Great Refusal”.

Over the subsequent decades, a couple of monarchs attempted to reign in London’s powers.

The first lost his head.

The second his throne.

The replacement monarch repaid London’s support with a Second Charter that stated:

“… citizens of London shall for ever hereafter remain, continue and … shall have and enjoy all their rights, gifts, charters, grants, liberties, privileges, franchises, customs, usages, constitutions, prescriptions, immunities, markets duties, tolls, lands, tenements, estates and hereditaments whatsoever”

London’s appetite for trade and riches exceeded what could be satisfied by the Crown. It ruthlessly sought mercantile opportunities beyond the shores of Britain, establishing the East India and Hudson’s Bay companies. Collectively these companies came to dominate trade and control vast portions of two continents.

These privately sponsored endeavours led to the establishment of the British Empire.

At its peak, London was the largest city in the world.

The centre of an empire covering a quarter of the globe’s landmass and population.

Fall of the British empire

Just 20 years later, Britain was losing World War II.

German bombs damaged or destroyed a sixth of London’s buildings.

Winston Churchill urgently sought American assistance with the war.

One of the founding principles of the United States was the freedom to drive a hard bargain. Like London, the Americans loved nothing more than maximise profits.

Sensing Britain was in a weak bargaining position, the Americans proposed a set of guiding principles governing how the world would be divided up after the war, if the Allies won. One of those principles effectively promised to dismantle the empire by agreeing to grant “the right of all people to choose the form of government under which they live”.

During the negotiations, Churchill reluctantly signed up to this Atlantic Charter.

Even so, Churchill failed in his attempt to get the United States to join the war. It took the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour a few months later to change their mind.

After the war, Britain’s empire rapidly shrank as former dominions sought self-determination or outright independence.

The fall from global power to opinionated small island was swift. This was mirrored by America’s rapid rise from an inward-looking sleeping giant to superpower.

With the empire crumbling, London switched its focus to dominating the world of Financial Services.

All change please

In recent times there has been a great deal of debate about the political shape and future of Britain.

Devolution delegated a wide range of powers from the national government to the nations of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

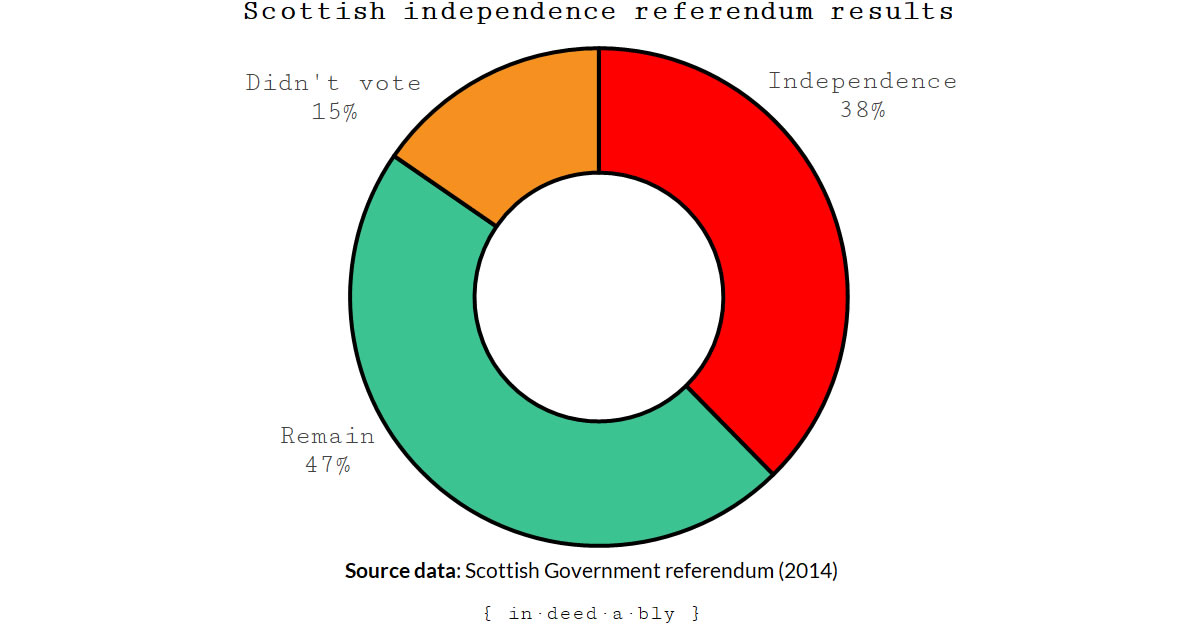

38% of eligible voters sought Scottish independence during a 2014 referendum. This accounted for almost half of the people who cast a vote.

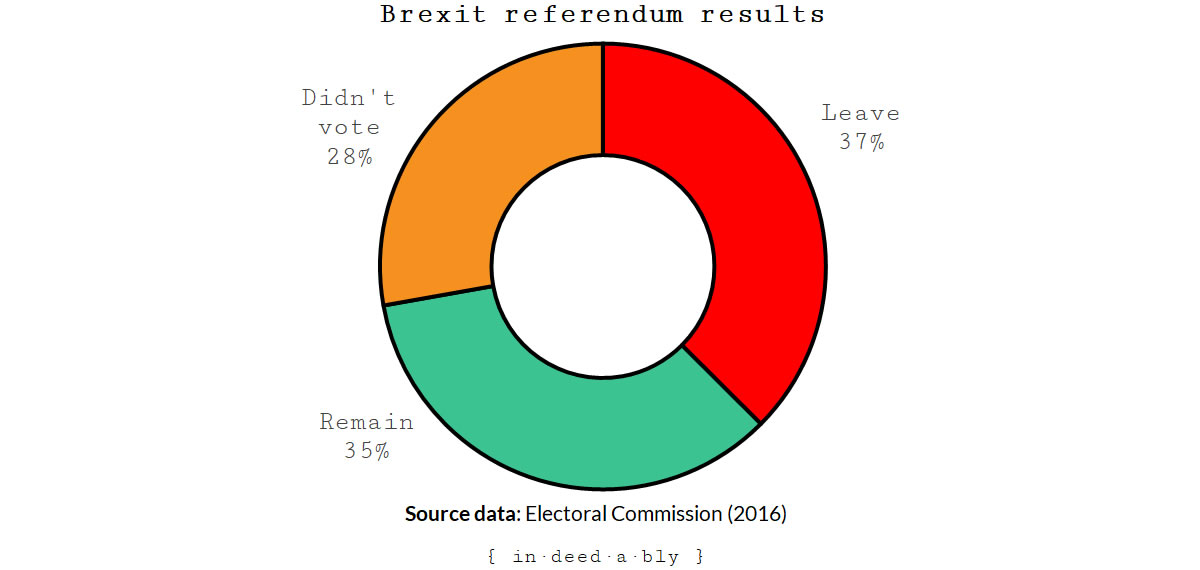

37% of voters wanted Britain to exit the European Union during a 2016 referendum. That was slightly more than the number of people voting to remain, while 28% of eligible voters didn’t bother voting.

A take away from those votes is that a vast portion of the electorate is either not wedded to the status quo, or simply don’t care.

Independence

Given the appetite for change, what might happen if London remained true to form, and put its own financial interests ahead of those of the rest of the United Kingdom?

According to a 2016 study, London contributes 30% of all tax revenues to HM Treasury.

That is more than the next 37 largest cities in the United Kingdom. Combined.

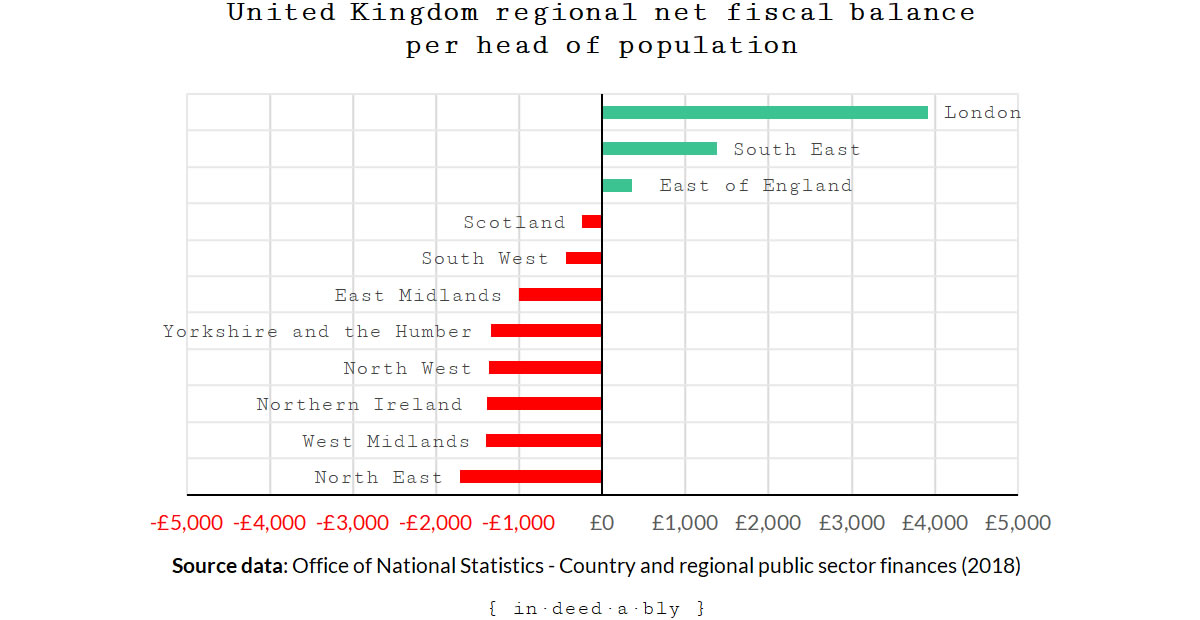

London is one of only three regions of the United Kingdom that makes a net positive fiscal contribution per head of population to the economy. The remaining regions are all net takers.

This raises the intriguing question: could London’s future prospects be materially improved by leaving the United Kingdom?

To declare independence?

To establish itself as an independent city-state hosting a global financial centre?

London’s commercial interests have often been at odds with the interests of the crown, and the rest of Britain. From the backing of George Washington during the American War of Independence, to almost bankrupting the country and collapsing the financial system during the Great Recession.

London’s vast banking and financial services industries are dependent on low friction access to international markets. The majority of London’s population voted to remain in the European Union during the Brexit referendum.

An independent City of London would be slightly larger than Monaco, and nearly six times the size of the Vatican. Both are viable nation-states.

However, with only 9,500 people living within the City boundaries, there would be a scarcity of skilled labour required to operate London’s financial markets.

Much of London’s lucrative Financial Services industry work is today conducted outside of “the square mile”. A more sustainable independent London would likely require reversing the “Great Refusal”, and expanding the boundaries of the City of London to include all of Greater London.

That would increase the population to over 8,000,000 people. It was also mean an independent London included airports, cultural amenities, hospitals, schools, and universities.

When I first considered the concept of an independent London, I dismissed it as a silly idea. However, as the Brexit process rapidly descended from farce to shambles, I found myself returning to the notion.

I must confess I haven’t been able to come up with many good reasons for London not to do it.

The main worry would be defence. The rest of the United Kingdom would experience a massive economic dislocation, losing their most lucrative industries and the goose who lays golden eggs.

Would the wreckers allow their meal ticket to simply walk away? I have my doubts.

References

- Andrews, E. (2019), ‘8 Reasons Why Rome Fell’, History

- BBC (2016), ‘EU Referendum Results‘

- BBC (2016), ‘A guide to devolution in the UK‘

- Britannia (2019), ‘Hudson’s Bay Company‘

- Cartwright, M. (2019), ‘William the Conqueror’s March on London’, Ancient History Encyclopedia

- Dalrymple, W. (2015), ‘The East India Company: The original corporate raiders’, The Guardian

- Department of State (1941), ‘The Atlantic Charter’, Office of the Historian

- Dsouza, D. (2019), ‘How London Became the World’s Financial Hub’, Investopedia

- en-topia (2014), ‘The London Evolution Animation’, The Bartlett Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (UCL)

- Electoral Commission (2016), ‘EU Referendum Results‘

- Elliot, L. (2017), ‘London economy subsidises rest of UK, ONS figures show’, The Guardian

- Faulkner, N. (2011), ‘Overview: Roman Britain, 43 – 410 AD’, BBC

- Glasman, M. (2014), ‘The City of London’s strange history’, Financial Times

- Greater London Authority (2018), ‘Focus on London – Population and Migration‘

- Hudson, J. (2011), ‘Overview: The Normans, 1066 – 1154’, BBC

- Inman, P. (2016), ‘London pays almost a third of UK tax, report finds’, The Guardian

- James, E. (2011), ‘Overview: The Vikings, 800 to 1066’, BBC

- Judd, D. (2011), ‘The decline and fall of the British empire’, BBC History Magazine

- McGough, L. and Piazza, G. (2016), ’10 years of tax. How cities contribute to the national exchequer’, centre for cities

- Office of National Statistics (2019), ‘Country and regional public sector finances: financial year ending 2018‘

- Office of National Statistics (2019), ‘Population estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: mid-2018‘

- Roumpani, F. and Hudson, P. (2014), ‘The evolution of London: the city’s near-2,000 year history mapped’, The Guardian

- Scottish Government (2014), ‘Referendum‘

- Taagepera, R. (1997). ‘Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia’. International Studies Quarterly, vol. 41, no. 3, pp475-504.

- William the Conqueror (1066), ‘The London Charter of Liberties’, City of London

[HCF] 30 June 2019

Oh, the good old question.

Would independence be beneficial? Yes of course.

Do we want independence? Yes of course.

Does it worth risking a war? Nope.

Well, at least in many cases the answer is that. In other cases no.

This is also an evergreen topic in my homeland.

Montenegro left the state union peacefully in 2006. Kosovo is a different story and an open-ended one. The independence of Vojvodina was a topic which came up a couple of times in the last almost hundred years since it was stolen from Hungary. Still, no one was so desperate to risk a war to reach that. As the main agricultural/food producer region of the country its independence would be huge kick into the balls to the southern parts. Many folks would loose that free ticket and that is not something the government would let happen on a peaceful way… like with a referendum…

Seeing London stepping on this path would be a very interesting thing. I know that in the western world such changes could start with a referendum. Still, I think that this would be so huge that it cannot happen on a peaceful way and that is not something I would really like to risk.

{in·deed·a·bly} 1 July 2019 — Post author

Thanks HCF.

Change is always hard, and unless there is a compelling reason to make the change then the status quo is less disruptive.

That is why the Brexit referendum made so little sense. There weren’t hundreds of thousand of people protesting that the United Kingdom should leave Europe. Most people still can’t articulate a cohesive argument for why doing so makes any sense at all.

Phil Money Mongoose 1 July 2019

I was also thinking along similar lines during the Brexit debate: what if England and Wales left the UK (and therefore the EU) leaving only London (maybe also NI and Scotland)?

{in·deed·a·bly} 1 July 2019 — Post author

Thanks for the intriguing idea Phil.

There is an “our way, or the highway” perspective amongst the particularly shouty Brexiteers (nearly all of whom are English) who seem to dominate the media coverage and debate. Those who don’t wish to leave (like Scotland) are actively (though half-heartedly) talking about alternative options like a second independence referendum.

That said, as the country sleep walks towards the latest arbitrary deadline, few people seem to genuinely believe that the UK will actually leave the EU. I’m not sure whether they think that at some point the leaders will spontaneously start to lead, or perhaps the tooth fairy will wave a magic wand and make it all go away like a bad dream.

Interesting times indeed.

OthalaFehu 1 July 2019

Lovely post. This is the sort of outside the box, but still relevant thing I enjoy reading. Could not believe the Scottish vote, Still watching what will happen with Brexit. Finally another country besides my own (America) is screwing itself over with no clear path forward. Making some more popcorn as we speak.

{in·deed·a·bly} 1 July 2019 — Post author

Thanks OthalaFehu.

The competition for who can kick the most expensive economic own goal certainly seems to be hotly contested. Maybe it should become an Olympic event? Not quite as exciting as the Rugby Sevens, yet compelling viewing in its own way.

Hette 3 July 2019

Have you considered the possibility that London is only big and powerful because it “feeds” off the rest of the country (or off Europe… or off the world)?

I understand that many of the brains and the money are in the big centres, but the physical resources are not, neither are most of the people who do the real grunt work of making or finding stuff so people in the big centres don’t need to. Ideas about how to improve also can and do happen outside the big centres of conformity.

I guess I believe that every society needs the built-up, crowded bits and the spread-out, empty bits to balance out and each thrives because the other exists.

{in·deed·a·bly} 3 July 2019 — Post author

Thanks Hette. You raise some valid points.

London certainly feeds off the whole world. It also (currently) enjoys a competitive advantage in supplying financial services and market operations at a large scale. Historically, that required physical proximity and a concentration of skills, which made it hard for other centres to compete.

Improvements in technology and communication have largely eliminated that physical proximity prerequisite, meaning financial centres offering substitutable services now largely compete on regulatory compliance burden and taxation policy.

Ideas can (and should) come from anywhere. It doesn’t matter who originates them, the best ideas should be adopted and applied to improve delivery of the desired outcome. Speed. Accuracy. Efficiency. Automation. Resource effectiveness. All the usual suspects.

The work, regardless of whether it be “grunt” work or highly skilled professional services, should be performed by those who are able to do a “good enough” job at the most competitive price.

Already much of the food and goods we consume are imported, I see skills as being no different. If a job can be adequately performed in a lower cost locale, then it should move there. If not, then a suitably skilled worker should be recruited to perform it in London.

When a Londoner desires open space larger than Hyde Park they could go abroad to experience it, in the same way they may go to Spain for the beach or Austria for snow.

An independent London would most likely require guest workers to function. My point here is that those workers should be selected based on willingness to work at a price determined by supply and demand, rather than physical proximity or historical ties.

HK Expat 8 July 2019

If London tried to declare independence over the views of the rest of the UK it would be very much in the position of Hong Kong now. Basically, it is totally reliant on the rest of the UK for the most basic of all commodities, namely water, that it would quickly be held hostage to the left over bits that any initial financial advantage would be arbitraged away, and then some!. Let alone electricity, gas, petrol supplies etc…Nice idea but simpily unworkable.

{in·deed·a·bly} 8 July 2019 — Post author

Thanks for your thoughts HK Expat.

In a world of international trade, obtaining things a country naturally lacks is achievable, though potentially expensive. Of course that is dependent on the country having something of value to sell so they can finance that trade.

There would certainly be some significant one-off costs involved initially, such as the construction of desalination/treatment plants on the Thames, storage reservoirs, re-establishing commercial shipping facilities, and so on.

You raise an interesting parallel with Hong Kong. Like London, many of their present challenges stem from having its destiny and direction of travel determined for it by a collective that doesn’t share its values or goals.

Ironically, that line of reasoning was also used by Brexiteers to justify leaving Europe!