I silently cursed, as I wormed my way underneath the kitchen sink and attempted to identify the source of the water leak.

Pat prattled on about the triumphs and tragedies her thoroughly unmodernised kitchen had witnessed during her 50 years of home ownership. A hip replacement had restored her ability to get around town unaided, but cost her the flexibility required to look under the sink herself.

I had mostly tuned her out, as she recounted stoically battling to pay off her mortgage while raising a family on a single annual wage of just £2,000.

Through recessions.

Rampant inflation.

Double-digit rates of unemployment.

Mortgage interest rates in the mid-teens.

Pat grabbed my full attention when she mentioned the purchase price she had paid for the house.

“How much?” I demanded, reflexively attempting to sit bolt upright, and seeing stars as I brained myself on the underside of the sink.

“£6,000. That was a lot of money back then.”

The economy class school holiday airfares on my family’s recent trip home had cost nearly £6,000!

Today Pat’s house is worth over £1,400,000. Now that is a lot of money.

Or is it?

Apathy for the win

That evening I ran the numbers to convert Pat’s £6,000 from 50 years ago into today’s money.

£97,000.

She was right, it had been a lot of money.

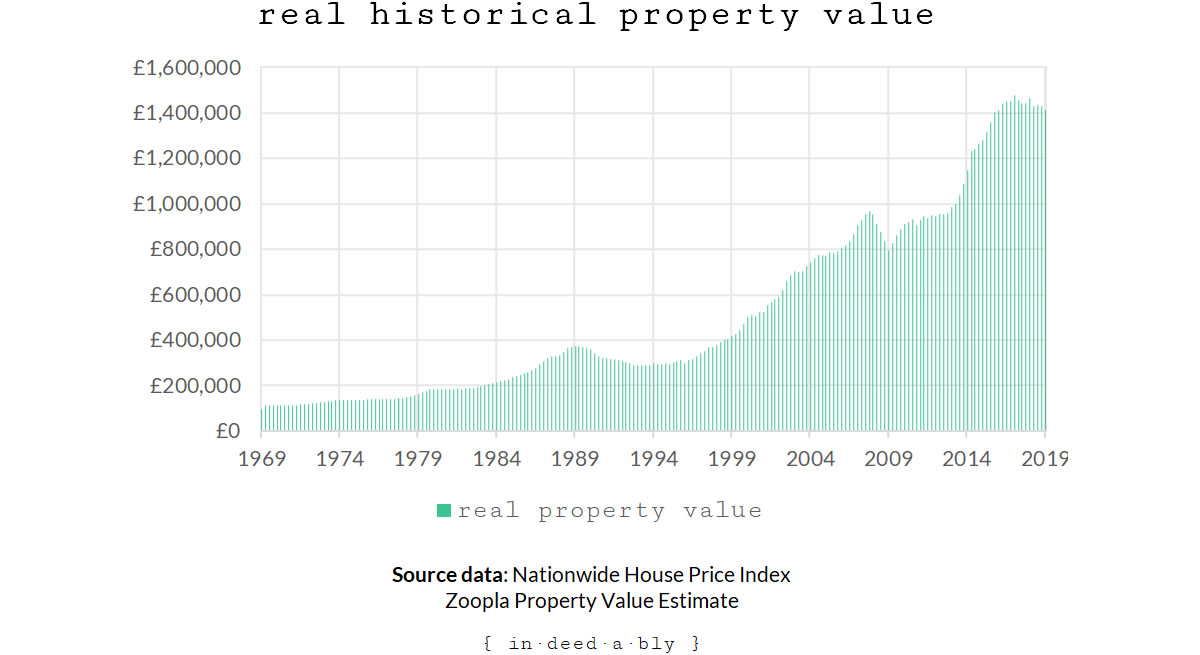

Throughout 50 years of home ownership, Pat had enjoyed a real compound annual growth rate of 5.48%. It hadn’t been a smooth ride, but over the long term there had been more ups than downs.

That got me wondering. Had Pat been an investing genius?

Spectacularly lucky?

Or just extremely patient?

Pat had initially made a one-off investment decision. However, it was what she did not do that accounted for the bulk of her subsequent wealth generation.

Avoiding the vast financial friction that comes from relocating.

Choosing the magic of compounding over the termite-like hollowing out of their net worth, that occurs with each relocation.

- Stamp duty.

- Conveyancing.

- Connection fees.

- Removalist costs.

- Replacing furniture that no longer fits.

Zoopla reports that the average British person relocates 8 times throughout their lifetime. Once they purchase their own home, they stay put for an average of 23 years. The more expensive the property, the longer the tenure of ownership.

Things only look cheap in hindsight

£6,000 seemed like an enormous figure 50 years ago but today looks ridiculously cheap.

Except here is the thing: things only ever look cheap in hindsight.

Despite all the bellyaching about property affordability, in 50 years time that £1,400,000 will likely look similarly cheap.

To illustrate, suspend disbelief for a moment and pretend that real compound annual growth rate continues for another 50 years.

Pat’s house would be worth roughly £19,500,000 in today’s money.

Not a Chelsea townhouse.

Nor a Holland Park mansion.

Nor the Scottish isle or entire rural Welsh village that such a sum could purchase today.

No, it would buy that same uninspiring mid-terrace house, with dodgy wiring and rising damp, located on a suburban London road full of identical houses suffering similar problems.

You have to live somewhere

Everyone needs a home. That warm safe place they go to escape the demands of the big bad world.

Some folks thrive in the flexibility of renting. Happy to avoid sinking endless time and money into home improvements, gardening, and DIY projects.

Others prefer the feeling of control and certainty that only owning their own home can provide.

A once common third approach embraced the best of both those options:

- Rent in a location that supports your desired lifestyle.

- Own buy-to-let property elsewhere, in promising locations poised for capital growth, while being attractive to prospective tenants.

In recent years the government has reduced the attractiveness of that third approach. An aggressive social policy agenda has led to a series of tax, compliance and tenant protection measures being introduced with a collective policy goal of discouraging private landlords.

I have long pursued that third option, paying far too much rent for a house conveniently located for a short commute to the city and within the catchment area of some outstanding (free) state schools.

Meanwhile, I operate investment properties with excellent growth prospects in areas where I have absolutely no desire to live.

Lately, I have started to question whether my approach is achieving the optimal outcome.

- In part, this has been triggered by the erosion of investment returns from buy-to-let as an asset class.

- In part, it is the long-running war of attrition that my lady wife has waged, frustrated that her participation in the never-ending home decorating one-upmanship games played amongst her friends has been thwarted by our status as tenants.

- In part, I tire of the endless chasing of my recalcitrant landlord over outstanding repairs and long-neglected maintenance, while my own tenants and property managers chase me about the same.

Perhaps there is something to the conventional wisdom of “bricks and mortar”?

It had certainly worked out nicely for Pat.

A question of timescale

I have a theory that capital growth makes you rich, but cash flow that makes you feel rich.

This makes the question of home ownership an interesting one. As Pat’s experience has shown, the timescales of the homeowner play a huge role in their cash flow profile and housing wealth.

capital growth makes you rich, but cash flow that makes you feel rich.

Short term

Over the short term, renting tends to be cheaper than owning.

The transaction costs associated with buying property are vast, both in terms of financial and emotional cost. Dealing with unresponsive conveyancing solicitors, voyeuristic lenders, slimy estate agents, and the collective indecisiveness of a property chain can be exhausting.

Cashflow winner: Renting

Wealth creation winner: Renting

Medium term

In the medium term, renting tends to cost more than the property holding costs and mortgage interest, but less than the total mortgage payment.

Should the rent fail to cover these costs, then the landlord would be running a loss-making business, effectively subsidising the living costs of their tenant.

Conversely, if the rent exceeded the full ownership costs, including the mortgage principal, then the logical course of action would be to own rather than rent.

Cashflow winner: Renting

Wealth creation winner: Owning

Long term

Over the long term, the mortgage gets paid off. At that point funds that were previously servicing debt suddenly become free cash flows.

Alternatively, some owners choose to perpetually run interest-only loans. This allows inflation to erode the real value of the debt, while maximising cash flows over the life of the loan.

In either case, property prices in areas close to good employment prospects generally rise over time, generating wealth for the owner.

Cashflow winner: Owning

Wealth creation winner: Owning

The inevitability of riches?

Having established the existence of several distinct cash flow and wealth creation patterns over different timescales, let’s test how my theory plays out over the 50-year projection for Pat’s house.

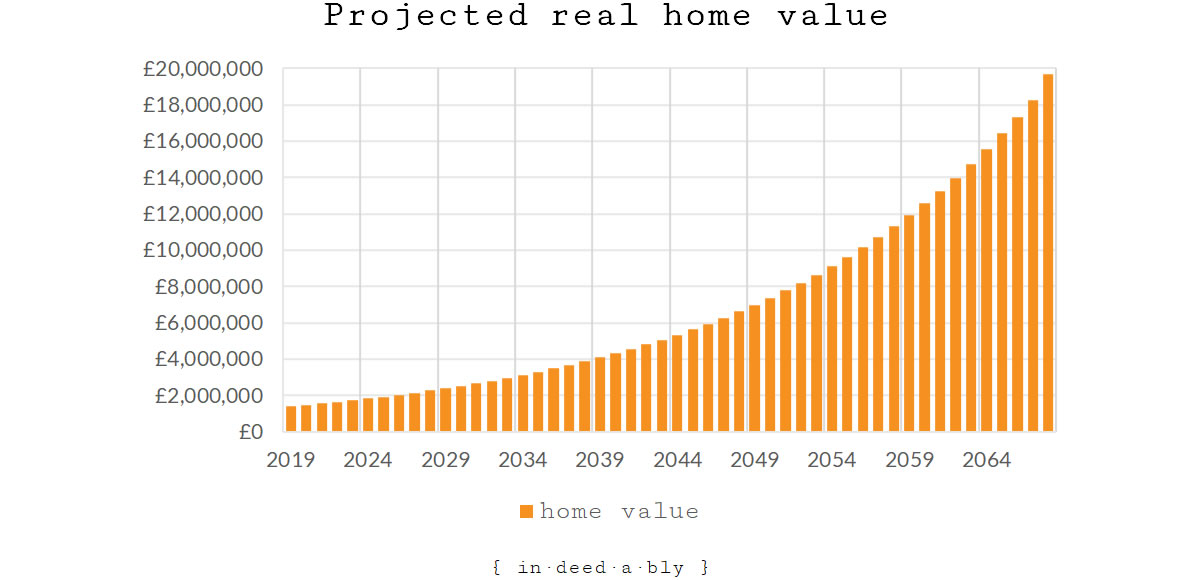

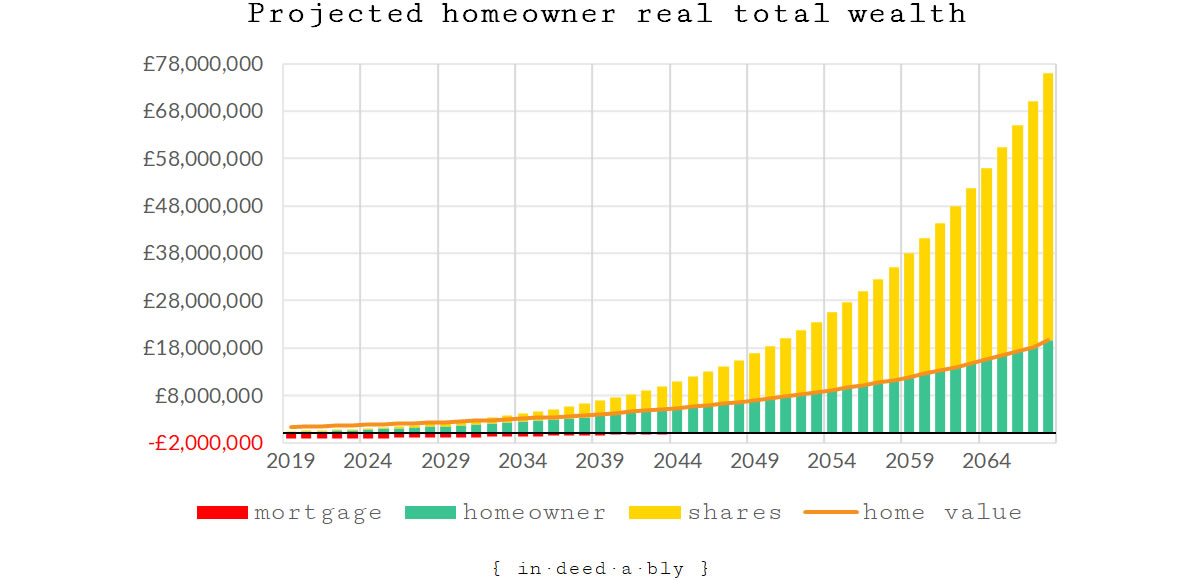

The first chart displays the projected value of Pat’s house over the next 50 years.

To begin with, some working assumptions. In real life the ride is unlikely to be this smooth:

- All figures are expressed in 2019 money.

- The house continued to grow at a real compound annual growth rate of 5.48%.

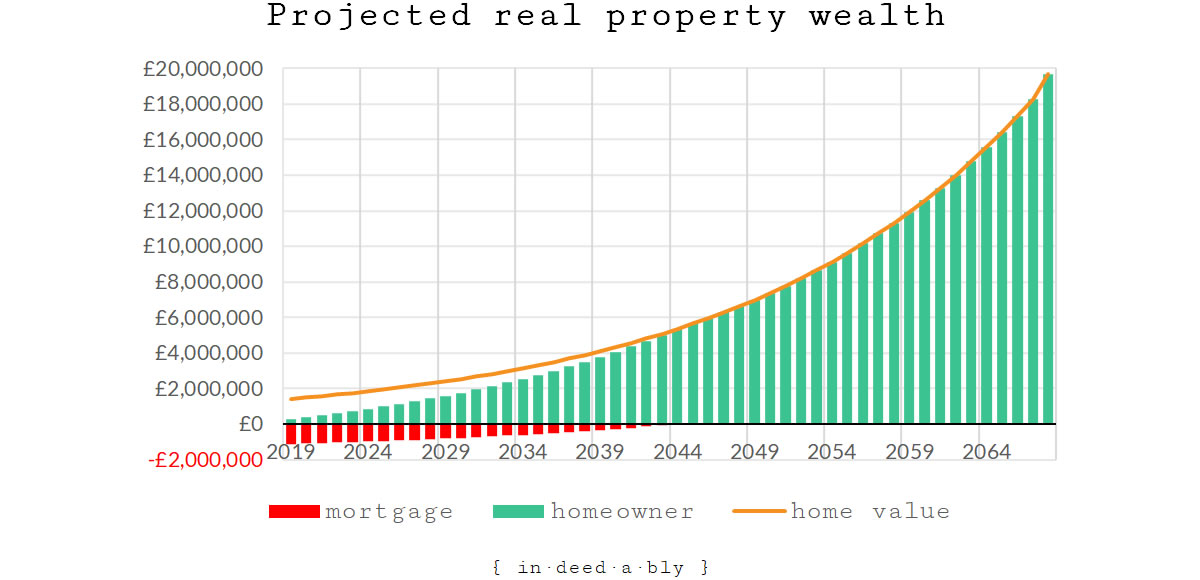

In the absence of a lottery win or access to the Bank of Mum and Dad, the homeowner needed a mortgage to finance the purchase.

The second chart displays how their property wealth accumulates over time.

- A 25-year repayment mortgage was used to finance the property purchase.

- The mortgage had a fixed interest rate of 4.7%, the long term historical BoE base rate.

- The tooth fairy benevolently contributes £300,000 towards the deposit and buying costs.

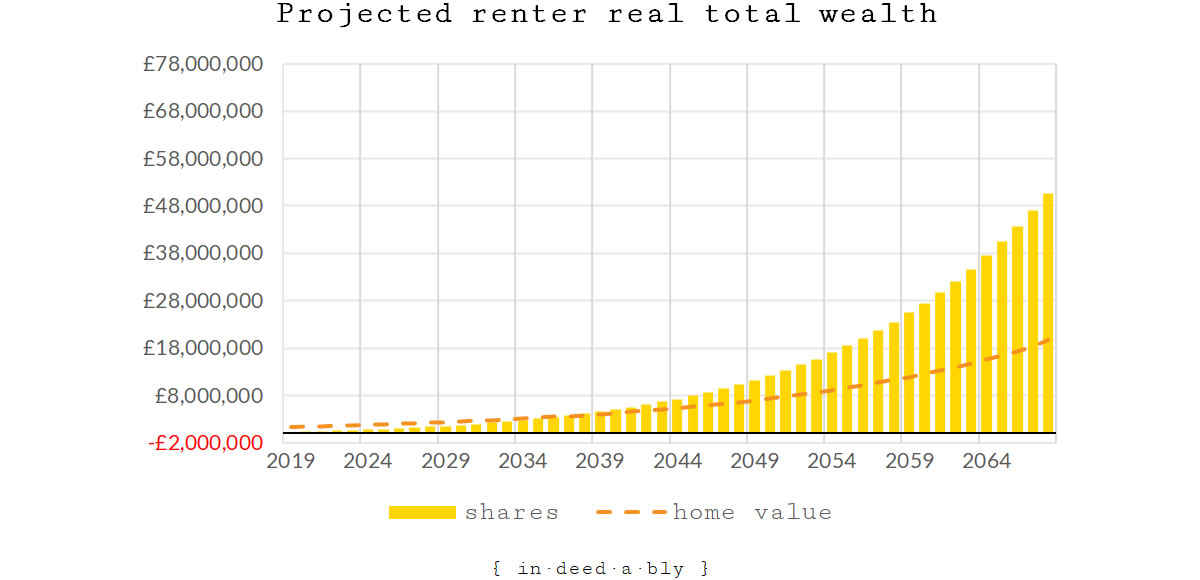

Meanwhile, the renter invests surplus cash into their favourite low-cost global index tracker fund.

Some more assumptions:

- Rent is assumed to be 2.75% of property value, based on comparable Zoopla rental listings.

- Income is deemed to be 250% of rent.

- The real expected annual total stock market return is 6.1%.

- All buybacks and dividends are reinvested.

- The tooth fairy doesn’t play favourites, donating £300,000 seed capital to the renter.

The home value line is displayed for comparative purposes.

In this case study, the homeowner pursues a similar investment strategy to the renter, investing any residual income after their housing costs are met.

Once the mortgage is paid off the surplus free cash flow that is available to invest increases considerably.

Yet more assumptions:

- The homeowner and the renter maintain identical incomes throughout.

- Annual property maintenance costs are deemed to be the equivalent of four weeks rent.

I must confess I was initially surprised at the magnitude of the difference in accumulated wealth between the homeowner and the renter by the end of the 50-year projection. Investing other people’s money is a powerful thing indeed!

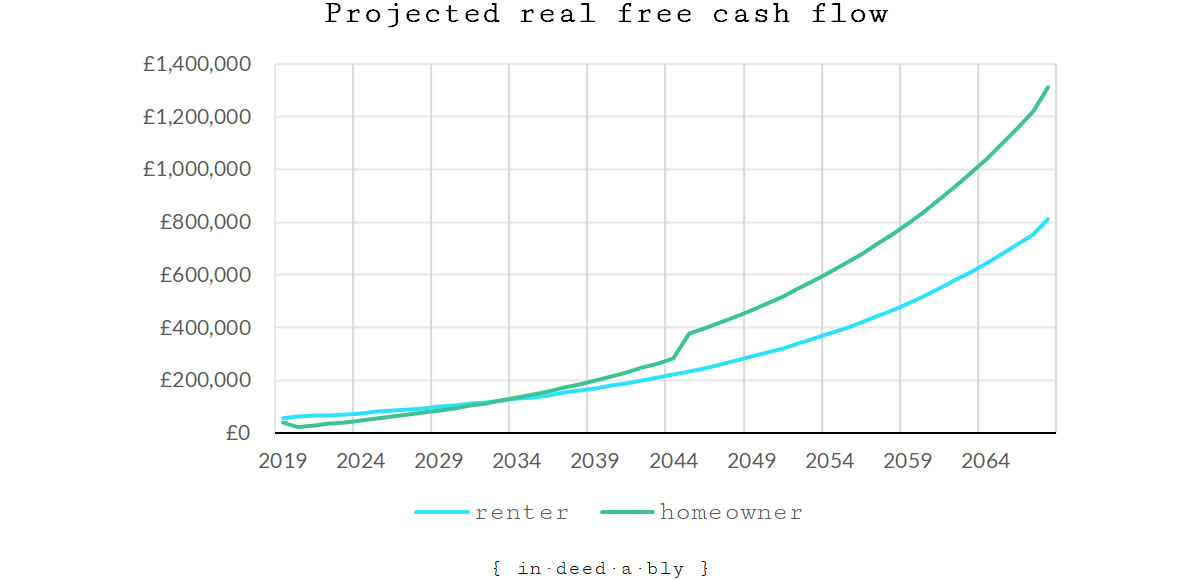

The final chart brings my theory to life nicely. It plots the free cash flows after housing costs for each of the homeowner and renter over the 50 year period.

Initially it costs more to be a homeowner.

However, the renter’s housing costs are indelibly linked to the underlying value of the property they occupy. As property prices rise, so too does their rent.

At some point the cost of renting will start to exceed the mortgage payments.

From that point onwards the homeowner is in an advantageous cash flow position, as well as benefiting from the capital growth of the property.

Once the homeowner has paid off their mortgage entirely, their housing costs reduce to just that required for ongoing maintenance.

Challenge the premise

We shouldn’t read too much into the actual numbers displayed in this case study. There are at least a dozen assumptions baked into the analysis, any of which could quite reasonably be challenged.

History doesn’t repeat exactly, yet we do see familiar patterns reoccurring on occasion.

Change is constant. Life feels like a rollercoaster while we are leading it, yet when viewed over the long term that bumpy ride tends to smooth out.

It was the final chart, contrasting the free cash flow paths over time, that has challenged my premise on homeownership.

The results shouldn’t have been surprising, confirming the rules of thumb about timescales and outcomes I proposed earlier.

However, seeing them brought to life so vividly has given me pause.

My theory about capital growth making you rich holds true, but it is that rich feeling of having free cash flow which powers that growth.

I don’t want to live in my current neighbourhood forever, as Pat has remained in hers. Before long my kids will have outgrown the need for those school catchments, just as I have outlived my desire to work in the city.

I do want to live next to the beach one day. After analysing this case study, that house should be one that I own.

Outright.

Soon.

References

- Bank of England (2019), ‘Inflation calculator‘

- CAGRCalculator (2019), ‘Reverse CAGR Calculator‘

- Greater London Authority (2016), ‘Economic Evidence Base for London 2016‘

- HM Land Registry (2019), ‘House Price Index‘

- Investopedia (2019), ‘Compound Annual Growth Rate‘

- Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2019), ‘English Private Landlord Survey 2018‘

- Nationwide (2019), ‘UK House Prices Since 1952’, Nationwide House Price Index

- Nationwide (2019), ‘Seasonally Adjusted Regional Quarterly Indices’, Nationwide House Price Index

- White, D. (2017), ‘How often do we move house in Britain?, Zoopla

- Zoopla (2019), ‘House prices‘

- Zoopla (2019), ‘Property to rent‘

- Zoopla (2012), ‘The average Brit “will move house eight times”‘

Nick @ TotalBalance.blog 7 May 2019

Good stuff!

Looking forward to seeing those beach pics soon then.

Have you gotten your beach-body ready yet? 😛

It’s always nice to see graphs that emphasize something that you kind of already knew 😉

It’s my clear understanding that few renters today, who believe “renting is cheaper than owning” would actually change their mind, even if you showed them this (I am gonna try though!).

Also, I think there is an overweight in people who own and invest at the same time, but I have no evidence to back this theory up. I think you (as a current renter and investor) is a minority in the group of renters 😉

Also, many of the people who opt to rent their home do it for emotional reasons. “I feel more free this way”. There’s a huge group of people, who would care diddly-squat about those fancy financial charts…And to me, this is the main difference between the groups. I can definitely relate to the “emotional attraction” of renting though.

{in·deed·a·bly} 7 May 2019 — Post author

Thanks Nick.

My way of thinking has been that renting is primarily a lifestyle choice, rather than a financial one.

For many years I bounced around between countries and clients, following wherever fate and fortune lead me. In many cases hindsight should have me kicking myself (my lady wife certainly does) for not buying property in a given location, but the ability to pack up and go where opportunity led was a key part of the lifestyle I enjoyed.

Having school age kids has slowed that down considerably, and I suspect my tenure in my current house is the longest I’ve lived anywhere since childhood.

It is always good to challenge premises, especially long held ones, even if doing so reveals uncomfortable truths.

I’m all set for the beach: back hair is plaited, one pack stomach is oiled up, and budgie smugglers are on. Apologies to my more sensitive readers, but some mental images cannot be unseen! ?

Dr FIRE 7 May 2019

Good to see numbers and graphs confirming something that I’ve assumed for a while now. In the short term, renting is cheaper than owning, especially if you intend to move house in less than 4-5 years. However, in the long term, owning a house and staying there for 10+ years is the best, especially once the mortgage is paid off and you have all that extra money to make use of.

I personally would like to buy a house at some point in the near future, but changing job locations every few years right now makes that unfeasible. But, one day. The idea of not having to pay rent/mortgage one day is just far too appealing.

I agree with Nick above, looking forward to reading posts on how you go about sculpting your beach body!

{in·deed·a·bly} 7 May 2019 — Post author

Thanks Dr FIRE.

You could always figure out where you want to end up, buy there soon, and rent it out until you’re ready to live there yourself. If history is any guide, they are more likely than not to get more expensive over time. Gives you the best of both worlds, until you’re ready to settle down in that one place.

On the beach body, there are two schools of thought.

I know which look I’ll be rocking! ?

Dr FIRE 7 May 2019

That is an option, and something that I have given some thought to, but maybe not enough. One problem is that both the Lifetime and Help to Buy ISAs can only be used if you plan to buy a house to live in; you can’t use one or the other for a buy-to-let mortgage. This is an issue, as I’ve already moved some money across to a Lifetime ISA for that government bonus!

I’m hoping to be in a position to settle in the next 5 years – this gives my girlfriend time to finish her PhD and to start full-time employment, and for me to find a job that isn’t a short fixed-term contract. Obviously things can change, but that is the current plan.

I was only joking about the beach body. For better or for worse, I also fall into that second category!

{in·deed·a·bly} 7 May 2019 — Post author

Sounds like an opportunity cost decision Dr FIRE.

If the anticipated price rise exceeds the value of the government match (plus any withdrawal penalties) then withdrawing the cash and eating the hand out would make sense. If the reverse is true then leave the funds where they are and buy something whenever you’re in a position to live there personally.

The magnitude of my beach body sexiness simply cannot be measured! Good to hear we’re kindred spirits in this. ?

FIRE v London 7 May 2019

To what extent does your case study lead to a different conclusion if long term house prices simply track earnings? My hunch is that prices in top cities can’t continue over the next 50 years as they have over last 50 years. Mainly because interest rates finished the last 50 years almost at rock bottom. And they can’t continue falling over the next 50. And if earnings rise by roughly the same as the price of a mortgage then the leverage argument in favour of property is much weaker.

Plus there is a flexibility premium (embedded option?!) that comes with renting which I think is an important consideration.

So if I were you i wouldn’t jump at the beach house just yet.

{in·deed·a·bly} 7 May 2019 — Post author

Thanks FvL, you raise some excellent points.

I think the historical relationship between property prices and local earnings has already fallen away to a large degree. Property investment has become a global game, with investors parking money where they identify growth potential (or a safe store of value). The prices they pay aren’t tethered to the local wages, as ably demonstrated in a host of places including London, San Francisco, Singapore, Sydney, Vancouver, and Wellington over the last decade.

That said, I share your feelings that it is difficult to see prices continuing to climb at similar rates in London as the last 50 years.

Supply and demand dictate what happens to prices. The current fad of nationalism, raising the draw bridge, and keeping the foreigners out hamstrings one major demand driver. The bulk of the folks who were going to domestically relocate to the big city for work have already done so, meaning unlike in developing countries there aren’t vast hordes of agrarian or industrial workers who are yet to make the move to the big city and push up demand.

I do rate the growth prospects of rapidly growing cities in India, Pakistan, central and eastern Africa. Not so much London, particular if Brexit happens.

The beach house is a lifestyle dream rather than a financial one. The desired outcome is known even if the timing and justification remain uncertain. Betting too large a portion of my net worth on the (often terrible) economic prospects of a coastal town would compromise my “work a little, play a lot” lifestyle.

It would also likely see me divorced, as my lady wife is firmly entrenched in London town! ?

FIRE v London 7 May 2019

Good for her…

{in·deed·a·bly} 7 May 2019 — Post author

I appreciate the irony of your challenging the premise that I used to challenge the premise FvL. Less so your siding with my lady wife about our living location of choice. I fear you may be somewhat biased, the clue being in your name! ?

The charts below play out your suggested scenario of property prices tracking earnings. Historical real earnings growth is 1.05%, so I have substituted this for the real CAGR figure used in the projection discussed in the post.

First we have the renter’s total wealth.

Second the homeowner’s total wealth.

Given the large difference between the anticipated real total share market returns and the projected property price rises, they came off second best in this scenario. The renter’s total wealth finished up roughly one third greater than that of the homeowner.

Third we have the cashflow comparison.

While the pattern is similar, the lines don’t cross until the mortgage has been paid off. From that point onwards the homeowner once again surges away from the renter, due to their increased free cash flow.

Phil - Money Mongoose 7 May 2019

I applied a similar approach, my rental income is automatically invested into a fund. However, I think I would have done better off had I sold the house and invested the entire capital into the fund.

{in·deed·a·bly} 7 May 2019 — Post author

Thanks for reading Phil.

Renae 9 May 2019

I see it more like a sequencing problem. If you get a mega-McMortgage first up, before you have saved, say 50% of your early retirement dollars, into stock investments, then 30 years later, compounding interest has all this time been working against you and for the bank. You have $0 invested, the costs of a house to maintain, and you must keeping working. What if you saved for yourself first, by living in a cheap rental, and invested the difference between what your rent is, and your ideal mortgage repayment (assuming interest plus principal repayments). Once you hit 50% of FIRE target in investments, let that coast, then think about mortgaging yourself up to the eyeballs for your lifestyle choice. That way compounding is working for you, as well as against you. It will also make you really pay attention to whether your lifestyle choice mortgage is worth the sacrifice of extra years working to pay it off. What do you think? Holes in this idea?

{in·deed·a·bly} 10 May 2019 — Post author

Thanks for sharing your thoughts Renae, you suggest an interesting approach.

It could be argued that a well located property will also benefit from compounding as house prices rise. Take Pat’s house as an example, when she purchased it for £6000 that was the average house price in London. Today the £1.4m market price is worth double London’s current average. An example of compounding at work.

The key point there was location. A well located property in an area with strong economic prospects should outperform the prevailing market. It costs more to buy in, but demand driven by the attractiveness of the location should see more people wanting to live in that neighbourhood than moving away, pushing up prices.

Contrast that to the “cheap” option favoured by some elements of the UK FIRE scene. Buying a modest home, in a dodgier part town, located at the end of an epic daily commute from the nearest employment centre. It was affordable on the way in because it resided in a less desirable location. Unless some massive infrastructure spend fundamentally changes the economics of the area, then that undesirable location will experience slower price appreciation because of lower demand pressures.

From a cashflow perspective the “cheap” property is accessible sooner, due to the lower deposit and acquisition costs required. The lower purchase price means lower repayments, or potentially paying the mortgage off faster.

The more desirable, more expensively located property would require more of a run up. Larger deposit, larger acquisition costs, larger and potentially longer mortgage payments.

The individual must make an opportunity cost judgement about the competing anticipated returns:

The main challenges with tying up a large portion of a person’s assets in their own home are:

However that equity can be borrowed against and invested in something that mitigates those risks and does generate free cash flow.

Phil MoneyMongoose 10 May 2019

One problem with this approach is that it assumes the mortgage is more than the rent so you have a difference to invest. It could quite easily be the opposite. In a bull market, a property investment also benefits from leverage. I think the real factor is that most people are bad at saving/investing and a house is a forced long term investment. If people were equally disciplined to invest into the stock market, I’m sure they would do as well or better financially, but I don’t think this is the case.