Henrik had a gift. He could craft beautiful, simple yet elegant algorithms that enabled computers to do amazing things while consuming remarkably few resources.

This is the programming equivalent of Hans Zimmer composing a film score, or Serena Williams making it look like she has the ball on a string during a Wimbledon final.

50 years ago all programmers had this gift. It was a core skill. A prerequisite to competence.

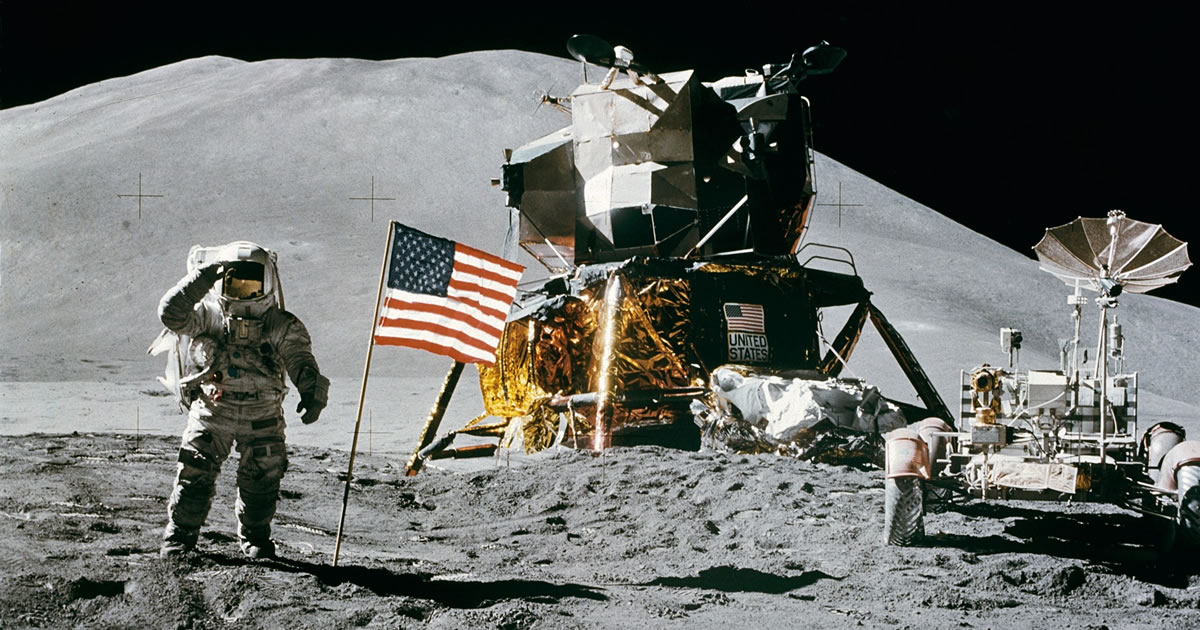

When Margaret Hamilton led the NASA programming team that wrote the control programs required to put a man on the moon, it had to run in just 64 kilobytes of memory.

By way of comparison, the “smart” TV in your family room contains more than 30,000 times the amount of memory that was available to NASA. If you’re anything like me, the most productive thing you’ve done with all that computing capacity is watch Game of Thrones!

Today an alarming number of programmers couldn’t write the simplest of “Hello world!” programs within NASA’s constraint.

Landing on the moon using just 64 kilobytes of RAM. Image credit: WikiImages.

Henrik’s talents were noticed.

A headhunter aggressively sought to recruit him.

Huge base salary. Sign-on bonus. Relocation package.

Henrik figured that writing computer programs was writing computer programs. The code was much the same regardless of whether it ran on a laptop or a car or a dishwasher.

A new beginning

His new employer was a medical technology company. They needed someone to write programs to control embedded medical devices, like pacemakers and insulin pumps.

Day 1

Henrik arrived at the lovely office and met his very relaxed boss and friendly colleagues.

At some point during that day, it occurred to Henrik that the medical devices had very limited computing capacity.

This was going to be a challenging role.

Day 2

Henrik returned to the well-appointed surroundings and his genuinely lovely teammates. His enthusiasm was markedly more measured than the previous morning.

That day he learned that there was no way to update the devices in place. Software patches required patients to undergoing surgery.

He would need to be extra careful with his algorithm design.

Day 3

Henrik hadn’t slept well. His neck was stiff. His shoulders tense. His lower jaw ached from grinding his teeth, and he could feel the beginnings of a migraine coming on

Around lunchtime on day three, Henrik realised that a bug in his code may kill the person wearing the device.

No good can come from an overeager insulin pump or a pacemaker with a poor sense of timing!

Minor typo? Dead.

Rounding error? Dead.

Miscasting a variable? Dead.

Not cause some minor inconvenience due to system downtime.

Not cost the company a little bit of money in forgone profits.

Not incur regulatory fines or compliance penalties.

A bug in his code would actively end the lives of innocent customers.

Day 4

After another sleepless night spent tossing and turning, Henrik couldn’t escape the idea that his algorithms could execute people. His stomach churned. His skin was clammy. He felt lightheaded.

The way he saw it, innocently introducing a software bug would be manslaughter.

Doing a half-assed job, like coding with a hangover, would be the equivalent of murder.

The stress was overwhelming.

His heart raced.

His chest felt tight.

He felt like he was being crushed by the weight of such vast responsibility. If his work was anything less than perfect it would kill people of killing.

Henrik returned to the lovely office. He marched up to his relaxed manager, returned his sign-on bonus, and quit on the spot.

Today Henrik writes operating systems for electronic instruments and recording studio equipment.

The pay isn’t as good.

The code is little different.

Yet nobody will die as a result of a mistake, and Henrik sleeps well at night.

Nobody would die as a result of a mistake. Image credit: PublicDomainPictures.

Stress is self-induced

But here is the thing: Henrik’s stress was entirely self-induced.

There was no evil pointy-headed boss micromanaging him.

Nobody held a stopwatch whenever he went on a bathroom break.

Flexible working hours meant he was free to come and go as he pleased.

His salary was more than sufficient to comfortably cover his lifestyle costs.

Co-workers didn’t bully, harass, haze, or attempt bodily harm on him using office supplies.

There was little chance he would be shot at, blown up, imprisoned or physically endangered.

Yet despite the complete absence of all these external stressors, Henrik had never felt so much pressure.

Though it existed only in Henrik’s head, the stress was real to him.

The physical manifestations of that stress were visible for all to see.

Stress is fear

I have a theory that for the most part stress is born out of fear.

Typical everyday things people get stressed about include job interviews, public speaking, and money.

Yet the reason they get stressed is the fear of what might happen.

- Fear of ridicule.

- Fear of rejection.

- Fear of being found out.

- Fear of public humiliation.

- Fear of running out of money.

Nervous travellers are an interesting case. Getting wound up in anticipation of all the things that might go wrong on the trip, yet relaxing once they get underway.

They made it to the airport on time. Checked in their bags. Cleared security. From that point onwards everything is outside of their control, and all the traveller can do is surrender to the experience. Which is liberating in its own way.

Then there are the stressors of boredom and frustration, like being stuck in traffic or under-utilised in the workplace.

- Fear of wasting time.

- Fear of being late, or letting people down.

- Fear of not being where they are supposed to be.

A low boredom threshold

It was this last type of stress that reminded me of Henrik, during my recent winter working hibernation.

It was an undemanding engagement, working alongside a bunch of genuinely nice people, where I was left largely to my own devices while solving a fascinating tricky problem.

Unlike the vast majority of my previous clients, the project was tangibly helping people in need.

The client even paid my invoices on time, without any chasing.

And yet much of the time there I felt stressed.

When I analysed why that was, I realised I was bored and consequently I was also frustrated.

The glacial pace.

The change-averse working culture.

The disconnect between the organisation’s stated goals and behaviours.

A lengthy commute on unreliable London buses to bookend each day didn’t help the situation!

Achieving a successful outcome did not require my presence on site every day, the organisation just didn’t move that fast. Yet the terms of my engagement was “pay for play”.

I got paid based on whether I showed up, not what I achieved.

Misaligned commercials

This was a textbook example of misaligned commercials.

A client who forks out for services they don’t fully utilise. Paying a service provider to be available in case they might be needed. Not an effective use of their money or my time.

Under such circumstances the service provider has two choices:

- Accept money for services they aren’t actually rendering. Lucrative, but unfulfilling.

- Act as a shock absorber for the client’s lack of urgency, charging for the work actually done and eating the downtime. An ethical choice, but bad business.

An unspoken truth in the consultancy game is that this dilemma is all too common. A consultant costs their employer the same regardless of whether they are fully utilised or idling on the bench.

Therefore consultants quickly become masters of generating urgency and looking busy.

When measured by the pages written or the hours worked they appear to be superhuman.

Change that measure to business outcomes achieved or quantifiable value delivered, and many consultants suddenly appear to be very expensive. Often through no fault of their own.

The problem is that I have a low boredom threshold, and hate having my time wasted.

Which makes me a good service provider who expediently solves the client’s problems, but a terrible consultant because I don’t seek to profit from prolonging the problem.

Avoiding boredom has been a strong motivator for my postgraduate studies. The majority of more than one tertiary qualification has been completed during those idle moments on client engagements.

As is often the case, my boredom was an entirely self-induced form of stress.

Everybody is different

What was interesting about my boredom problem was that other people involved in the same project thrived in the environment.

Revelling in the endless circular discussions.

The absence of decisions.

The slow pace.

The Accounts Payables clerk who had performed the exact same data entry tasks for 18 years.

The Solutions Architect who had just completed his 30th year on site, yet still believed he would one day get to implement the system he first designed during his second year on the job.

It made me appreciate that everyone is different.

One person may see something that cripples them with fear, liquifies their bowels, and renders them unable to function. The next person may walk past without even registering that exact same thing may pose some form of danger. Simple examples include being scared of dogs or a fear of heights.

Thinking back to Henrik’s job, he was stressed out of his mind by mere prospect of an issue he perceived may one day occur. Meanwhile, that issue had never occurred to Henrik’s relaxed boss, and even after hearing Henrik’s concerns he did not share them.

My aversion to boredom is a minor problem in the scheme of things.

Yet I wonder how those at the extreme end of the boredom spectrum are able to cope. People like Jean-Dominique Bauby who suffers from “locked-in syndrome” or Robert Maudsley who has spent more than 40 years in solitary confinement. The United Nations goes as far as describing the lack of stimulation associated with solitary confinement as being cruel and unusual, a form of torture.

The one thing I have learned is that whether actual or imagined, issues are real to those who perceive them.

References

- Boyd, J.W. (2018), ‘Solitary Confinement: Torture, Pure and Simple’, Psychology Today

- Delistraty, C. (2019), ‘From Clay Tablets to Smartphones: 5,000 Years of Writing’, New York Times

- Ford, R. (2017), ‘Serial killer Robert Maudsley held in solitary for 39 years’, The Times

- Laureys, S., Pellas, F., Van Eeckhout, P., Ghorbel, S., Schnakers, C., Perrin, F., Berré, J., Faymonville, M., Pantke, K., Damas, F., Lamy, M., Moonen, G., and Goldman, S. (2005), ‘The locked-in syndrome : what is it like to be conscious but paralyzed and voiceless?’, Progress in Brain Research, vol. 150

- Saran, C. (2009), ‘Apollo 11: The computers that put man on the moon’, Computer Weekly

- Sony (2016), ‘Extending memory on android tv’, Sony Community

- VandeWettering, M. (2016), ‘Is it correct that the computer on Apollo had a memory of 71KB? How could it perform the tasks needed for a moon mission?’, Quora

- United Nations Officer of the Human Rights Commissioner (1984), ‘Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment‘

earlyretireman 3 May 2019

That’s an interesting post!

Stress is indeed very personal. As for me and as far as my work is concerned, the better I understood my strengths and weaknesses, what I loved doing and what I absolutely hated, the less stressed I got. But only in conjunction with the ability to say ‘no’ to superiors in case I didn’t want to take responsibility for an assignment.

I am definitely susceptible to stress, but I have become quite skilled at avoiding it.

{in·deed·a·bly} 3 May 2019 — Post author

Thanks Marc.

I think as we gain knowledge and experience we learn how to manage stress. What can be overcome, what can be avoided, when we are getting in over our heads, and so on.

This might even be one of the reasons older folks tend to be less flexible and open to change than younger folks who have less to lose.

Learning when to say “no” is certainly an important part of that equation.

Odysseus 4 May 2019

Hi!

Great post. Your introductory tales are very nice, as well as the layout and images. Congratulations.

I believe that stress can be triggered by different reasons. For me is the fear of fail and disappoint others, especially at work. So far I did not identify boredom as a trigger for stress for me.

Henrik’s case must not be as unusual as we think, but the reaction of quitting a well-paid job is probably not so common. I see it similar to the gilded cage. Most of them think that they will manage the stress…

I agree that some companies must rethink their way to measure employee productivity. There are many companies that count how many hours you spent in the office in opposite to the outcome that you generate. I even had managers that would walk to the cafeteria 2, 3 times a day to see who was expending time there.

All the best.

Cheers!

{in·deed·a·bly} 4 May 2019 — Post author

Thanks for reading Odysseus.

You make a good point about managing stress. Read a few blogs where people who have reached their point of “enough” financially, and a common observation is how the pressure lifts and the daily grind becomes much less of a hardship. Once working becomes optional, and walking away a realistic option, it often doesn’t seem nearly so bad.

Same person. Same role. Same site. Same boss. Same co-workers. Only difference is the mindset and attitude.

Cashflow Cop 4 May 2019

I love Henrik’s story.

Stress is such a massive problem in Policing at the moment. I guess it always has been, but it had been much more hidden. The problem is that there are many who still view stress as a sign of weakness.

There are officers who will not seek help for fear of a stress marker on their records which might inhibit their career prospects in certain roles such as firearms or child abuse investigations.

Pushed to the extremes, when stress spirals into depression, there have been officers who have taken their own lives. It’s sad that there is still no official record to document when this happens but there is a push for it.

Job related stress, no matter what field is a real thing. Although there has been initiatives to improve wellbeing and mental health in Policing, there is still such a long way to go. The stigma will be around for a long time to come yet.

{in·deed·a·bly} 4 May 2019 — Post author

Thanks for sharing your insights Cashflow Cop.

Unfortunately that “can’t cope with stress” black mark has existed in almost all the industries I’ve done projects in.

Sufferers get branded as being fragile, rendering them career terminal, and prime candidates for redundancy whenever the next round of downsizing occurs. The prevailing thinking appears to be that if someone can’t cope with the pressures at their current level of the corporate hierarchy, how in good conscience could they be promoted into a position of greater responsibility (and therefore stress)?

It shouldn’t be this way, but unfortunately this is the real world we live in.

For what it is worth, my suggestion for folks suffering overwhelming stress is that they should definitely seek professional help… but do so privately at their own cost, independent of their employer (and their employer provided health insurance). For all the trendy corporate doublespeak about “wellness“, there is a clear conflict of interest between the right outcome for the employee and that of the company. There should be no illusions about where the loyalties of the human resources department ultimately reside.

[HCF] 7 May 2019

I can totally relate to Henrik. Fortunately I never really had a stressful job. It came spontaneously but I would seek for it consciously if I had to. Back in the time, my family was curious if I would like to become a doctor or a lawyer and my solid answer was “no way”. This answer did not do anything with costly and lengthy education (maybe a little), the main reason was that I never wanted to be responsible for people’s life. I try to do my best in my projects but knowing that I could not cause any serious harm to anyone provides me with a peace of mind. Otherwise, I would bet that my productivity and quality of work would drop and I would probably end up like Henrik. It is also true that as years are passing we get better and better managing our circumstances and our reactions to the environment. By the way, have you seen psychologist Kelly McGonigal’s TED talk about stress? I like her point of view and tend to agree with her 🙂

{in·deed·a·bly} 8 May 2019 — Post author

Thanks HCF.

Another way of looking at it is that if we aren’t experience any stress at all, then we’re merely treading water. Not pushing ourselves. Not growing or developing. Not trying new things. Essentially avoiding the fear of the unknown by sticking to what we already know. A variant on this theme was Mr YFG recently writing about returning to the workplace in search of more stress.

However I think we all know how much (or little) stress we are comfortable with, and some of us might even know how much is too much.

For example surgeons thrive on mending people, yet many of us would find the idea of holding another person’s life in our hands incredibly stressful. Bomb disposal would be a hugely stressful job, yet some people make a career out of it.

The two most stressful “jobs” I have done were being a stay-at-home Dad with babies in the house, and being a palliative carer. Neither paid a penny. Both roles made my stint in investment banking seem easy by comparison!

The point is that we’re all different, and we each need to choose the right balance for ourselves. Too little stress and we stagnate, too much and we risk burning out.

I suspect that is a moving target, changing over time.

[HCF] 8 May 2019

I agree with you and I can assure you I don’t search for a slothy job 😀

I have been in such situations, often in the holiday season. At these occasions I find myself broadening my view in terms of trending technologies or pick something and hacking around with it.

What I wanted to emphasize is that not all stress is created equal. I am ok with realistic deadlines which gives a frame to a project and encourages us to do our best. In my opinion, it boils down to the worst case scenario. If that is something in the life-threatening range it would probably stress me out and paralyze me instead of pushing and motivating.