“A taste of freedom can make you unemployable”

Imagine what your working life might look like if you could perform the tasks you enjoyed, and skip all the administrivia and bureaucratic busywork.

The coder who invests their time crafting elegant algorithms, without having to complete change control documentation or worrying about usability issues.

A financial planner who creates perfect financial plans, without having to handhold jittery clients or talk punters down from flights of fancy like investing in bitcoin or attempting to short-sell Elon Musk.

The photographer or graphic designer who is free to concentrate on their art, without needing to compromise to the whims or questionable tastes of the paying client.

Sounds idyllic, no?

During my current winter working hibernation, I’ve been given an insight into how that dream might play out in reality.

This year the tricky problem I selected to help a client solve was in the charity sector.

It offered a change of pace. A different mentality. A previously unexplored sector of the economy.

Donning my rose-coloured glasses, I perceived an opportunity to do good.

To give something back.

To help people.

I naïvely imagined a site with little of the busy work, institutional silliness, or corporate bureaucracy.

Less of the politics and noise that makes getting the job done so difficult in large corporates.

Reflecting on that decision-making process now, I can only give a wry chuckle about having seen what I wanted to see!

There are few things more foolish than making a decision based on how we want the world to work, rather than how it actually does.

The reality of working in the charity sector has been eye-opening, and not at all what I was expecting.

The pithy Naval Ravikant quote above is a reminder to be careful what we wish for!

Contradictions

The charity sector turned out to be a seemingly endless series of contradictions.

Charities are businesses, who protest mightily that they are not.

They are remarkably adept at manipulating donors via the use of emotive imagery and marketing messages. The pictures might be different, but the methods differ little from the approach used to sell products ranging from holidays to retirement homes.

One charity I encountered even operated a profitable sideline licensing a vast library of stock images portraying many of the clichés we expect to see during media coverage of humanitarian crises.

- Starving children.

- Forlorn mothers nursing infants, bereft of hope.

- Photogenic people wearing national costumes.

- Smiling school children, dressed in neatly pressed school uniforms, being educated in a dirt-floored open-sided classroom.

Charities vie for our attention, and our money. Their competitors are retailers and other charities.

The effective ones operate a sales funnel process similar to those used by businesses ranging from software houses to insurance brokerages. Some of the most effective Customer Relationship Management capabilities I have encountered were run by not-for-profit organisations!

The better a charity markets itself, the greater their share of a donor’s wallet.

This can result in misaligned commercials. A temptation to focus on brand building and marketing, rather than channelling those funds into whatever cause the charity purports to support. Those branded sporting events and legions of chuggers harassing commuters on the high street do not come cheap!

Few donors bother researching what proportion of their donation actually goes towards helping people.

We all should. For two reasons:

- As taxpayers, we each indirectly donate to every charitable endeavour that receives government grants or tax breaks. These range from food banks and domestic violence shelters, to subsidised car manufacturers and coal mines.

- Much of the social safety net we take for granted is outsourced, delivered by charities rather than by the government directly. Feeding the homeless, charity shops, mental health support lines, providing meals and companionship to the elderly, and so on.

Charities sell experiences: the warm fuzzy feeling we get from helping others and doing good deeds.

The customers for this experience are the donors, volunteers and many of the charity’s own staff.

Constraints and compromises

An overarching theme running through the charity sector is the desire to minimise cost and expenditure, so that more money can be devoted to actually doing good deeds.

This creates some interesting constraints and unfortunate compromises.

Salaries are generally at the laughably low end of the spectrum for a given skillset.

Consequently staff turnover is high, and vacancies can remain unfilled for extended periods of time.

The sad economic truth is that many people can’t afford to work for a charity.

This results in the competency bar being set very low, and expectations lowered accordingly.

During my hibernation, I observed three distinct archetypes amongst charity workers.

True believers

There are a (very) few idealistic true believers. People who selflessly devoted themselves to the charity’s mission.

This group tend to be young.

Single.

Free of financial realities like servicing mortgages or paying for child care.

Independently wealthy

Next there were a sizeable minority who are independently wealthy.

They might have received an inheritance.

Married well.

Financially independent.

Or retired from a successful professional career elsewhere.

This group have the luxury of choice about how they invest their time, and as such can afford to perform charity work.

Many in this group possess specialist skills in areas like accounting, computing, human resources, or procurement.

The challenge they face is performing the mental acrobatics required to be content plying those hardwon skills for significantly less money than they could earn doing the same thing elsewhere.

For many of us, reconciling a purchase ledger would be too far removed from the buzz of tangibly helping people.

Especially when an alternative use of the person’s time may see them personally feeding the homeless in their neighbourhood, or helping to build an orphanage in an underprivileged village.

Everyone else

Finally, there are the rest. The majority of workers. Many of whom would struggle to get work in the corporate world.

- Too old.

- Migrants.

- Unskilled.

- Dated skills.

- Mobility constraints.

- Mental health issues.

- Criminal records or banished from their chosen profession.

- Requiring flexible working conditions located close to home.

Collectively these three groups form a transient workforce, with a low tolerance for bureaucracy and bullshit.

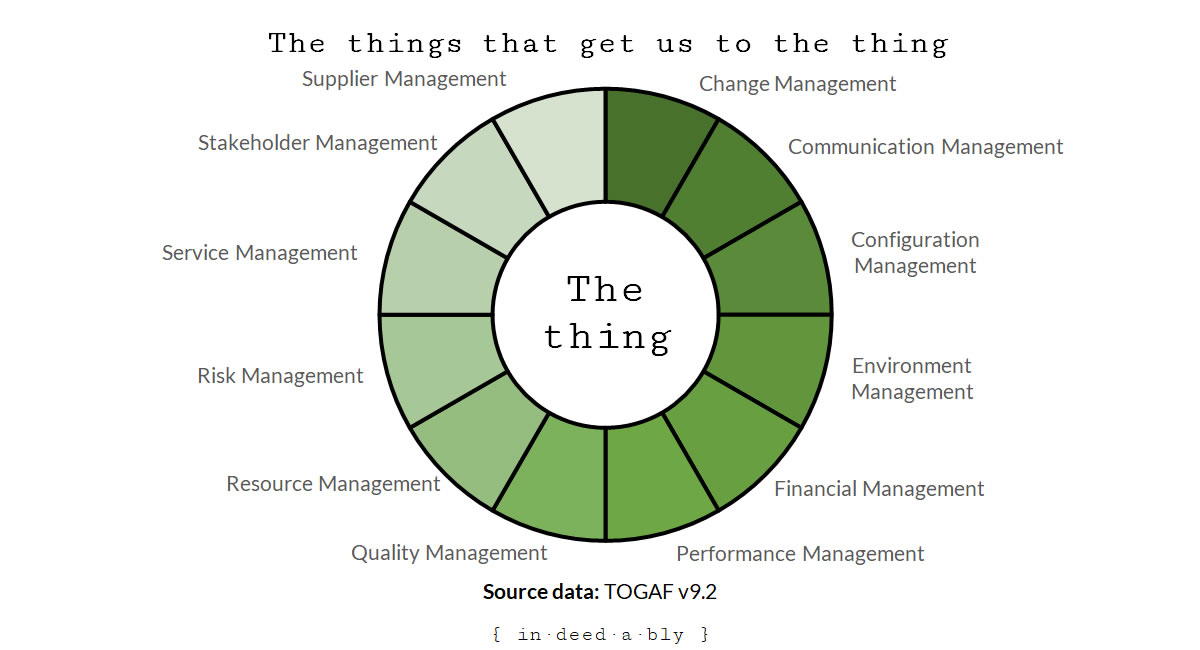

“The thing that gets us to the thing”

The Joe MacMillan character from the television show “Halt and Catch Fire” had a memorable line:

“Computers aren’t the thing. They’re the thing that gets us to the thing.”

His point was that before it becomes possible to attain a goal, there are often enablers and dependencies that must first be met.

Charities, like any business, have a whole bunch of support or back-office functions that are necessary to support the “front line” provision of whatever endeavour happens to be the charity’s mission.

The Open Group’s Architecture Framework provides a good overview of those supporting functions.

The majority of those support functions aren’t the stuff of rainbows and unicorns, regardless of whether they are performed by a non-government agency or a profit-seeking mega-corp.

- Controls.

- Governance.

- Oversight.

- Paperwork.

- Process.

The things most folks would happily skip past if given the option, so they could just do the fun stuff.

The problem is that by not doing these supporting functions well, the charity’s ability to efficiently and effectively perform its mission is compromised.

Donors would be horrified to learn their hard-earned donations were being set on fire or pissed up the wall. Yet, despite all good intentions, that is exactly what happens when “the things that get us to the thing” are neglected, poorly executed or ignored completely.

Uncharitable

Ironically, a penny-pinching operating model results in a great deal of inefficiency.

Processes tend to be manual and inconsistent, creating friction and duplication of effort.

Systems are more likely to be paper or spreadsheet-based than automated.

Managers have poor visibility of what is going on.

Policies are ineffectually enforced.

Accountability for failure is rare.

Decisions are ill-informed.

Controls are weak.

Fraud is rife.

The ability of the C-suite to do much about any of it is highly compromised!

By not viewing themselves as businesses, charities shun many of the standard tools and approaches that are widely used in the commercial world.

A “knowledge is power” mentality is commonplace.

Workers, who are fully aware they would have trouble landing a comparable role elsewhere, attempt to entrench themselves and become irreplaceable.

Decision making and procurement choices at middle management levels are dominated by job preservation.

When combined with the scarcity mentality, this produces inefficient and underperforming functions.

Widespread manual spreadsheet-based systems.

Informal relationship-based processes.

In-house developed technical solutions.

This yields a fascinating indirect outcome: the need for consensus-based decision making to get anything done.

Inevitably change is viewed as threatening.

Institutional politics and subversion are regularly deployed to undermine any initiatives that might alter the balance of power amongst the tiny siloed fiefdoms.

None of these problems are unique to the charity sector. That said, the only other environment where I’ve observed their collectively having such a debilitating impact on an organisation’s ability to perform its core function was a large, and thoroughly dysfunctional, legal partnership!

Airport security

My foray into the charity sector has taught me a number of lessons.

In many ways the charity sector is similar to airport security: visible, reassuring, yet largely ineffective. The virtue signalling of being seen to be doing good deeds is a primary driver for the industry.

The intent to do good often trumps how effective that doing good actually was.

An inconvenient truth is that the more effectively and efficiently a charity is at doing good, the larger the difference it is capable of making off the same donation base.

Consequently, a material portion of donations are wasted.

Not maliciously.

Not fraudulently.

But through apathy, acceptable incompetence, and a lack of accountability.

Charity occurs in unexpected places

An unexpected lesson I learned was that providing employment to folks who were unemployable is an indirect part of the charitable work performed by many organisations in the sector.

Initially I was appalled by this!

However the longer I worked at the site, the more I appreciated just how beneficial it was for a person to have a job.

To have a purpose.

A sense of identity.

A reason to get out of the bed in the morning.

It is true that many of these folks were well-meaning, yet hopelessly incompetent. However, as many of their jobs consisted largely of low-value busy work, this didn’t really matter.

The self-esteem and value they derived from holding down a job was priceless.

Once I understood this, I realised that it mattered much less about how ineffective the organisation was at performing its mission. Donations received by the charity were still assisting people in need, just those located closer to home.

That sat better with me than the donations lost to:

- attending luxury international charity conventions

- bribery

- corporate hospitality

- corruption

- fraud

- lobbying politicians

It isn’t the right answer, or solving the right problem, or doing it in the right way.

However in the absence of better options, it helps to do some good.

References

- Halt and Catch Fire (2017), ‘Halt and Catch Fire‘, AMC Studios

- The Open Group (2019), ‘TOGAF® Standard, Version 9.2‘

- Ravikant, N. (2018), ‘A taste of freedom can make you unemployable.’, Twitter

Dr FIRE 22 March 2019

Strangely enough, this post actually got me thinking about UK university tuition fees (specifically, the bit about how charities have a large amount of back-room work to keep the front-line provision of that charity, going):

At the moment, a student has to pay £9,250 for a year of university education. You might expect that all of that money is going towards paying for the staff that teach the students, and the materials required (books, chemicals in chemistry or physics, etc). However, I would imagine that most people would be surprised at how much money goes towards paying the pension of retired members of staff, maintaining old buildings, or towards research, rather than teaching. It’s obvious when you think about it, and is essential for the university to function properly, but is not immediately apparent!

Getting back to the topic at hand – I’ve never thought before that charities do a very good thing in providing meaningful work to those who might otherwise struggle to get it. I may not always enjoy my job, but it’s true that I do derive a sense of purpose and identity from it, and it’s only fair that everyone else should have that opportunity. Thanks for another thought-provoking post!

{in·deed·a·bly} 22 March 2019 — Post author

Thanks Dr FIRE.

I agree there are many similarities between the charity and tertiary education sectors. Certainly a lot of legacy costs, which can be met providing there is a strong sales funnel in the form of new students, particularly international fee paying students.

It will be interesting to see how they cope if Brexit occurs, as the education export sector is one of the most exposed industries to changing visa policies and international perceptions. Lose the funnel and those old buildings and legacy pension obligations become more than just inconvenient.

Mr. RIP 23 March 2019

Thank you!

This is THE post that gave a name to my gut feeling of “something being wrong” with charity in general.

Thank you! Amazing, brilliant post as always

{in·deed·a·bly} 23 March 2019 — Post author

Thanks for the kind words Mr RIP.

I think the charity sector is important and does vital work. That work is just often poorly executed, costing much more than it should due to people being people. I guess it is a bit like the wisdom of herds, things generally move in the right direction (albeit slowly), but within the herd there is all kinds of craziness going on!

I like the model the Gates Foundation uses, where they find a worthy cause, then find specialists who are good a doing whatever needs to be done to actually fix the problem.

Unfortunately some charities are a bit like consultancies or big pharma, realising in many cases that their existence relies on persisting problems rather than solving them. Too small to make a material difference, run by inexperienced people, and ultimately an inefficient use of precious scarce resource.

Caveman 24 March 2019

Fascinating look under the bonnet of some charities indeedably. I do give money to charity but I’m open with myself that it is, in part, to assuage my guilt that I’m not doing any real good.

When I no longer have to work for money I have some specific plans of how I want to give back by volunteering on nature projects. At least if I can see the hedgerow that i maintained at the end of the a day i know that I will have made a specific change rather than watching a direct debit go out every month.

Completely agree about the Gates Foundation. Applying business processes, metrics, planning and accountability means that they can take outrageous goals like ridding the world of malaria and be able to credibly explain how they are going to do it.

{in·deed·a·bly} 24 March 2019 — Post author

Sounds like a good plan Caveman, there is a lot to be said for the tangible.

The Rhino 24 March 2019

Haha, I don’t think my sister in law would have a job if it weren’t for the charity sector! Her employment history is patchy even there..

She’s a natural autocrat of highly questionable competence and accountability.

I’m not sure she’d last five minutes anywhere else?

{in·deed·a·bly} 24 March 2019 — Post author

Tell me honestly, does that not describe at least half the people that you’ve encountered on their career fast track towards the corporate C-suite?

The Rhino 24 March 2019

Only the 1st bit of my career (quite a while ago) has been in organisations big enough to have a C-suite and a track toward it so I’m not the best person to ask.

That said, I don’t think many are (true) autocrats because it is such a losing strategy from a social perspective. I think most with that tendency grow out of it at school (with any luck).

Its a shame really because it puts enormous pressure on relationships. Now she’s reached middle age she doesn’t have any friends left. It doesn’t make for a happy, easy-going life. Every interaction degrades into conflict.

weenie 24 March 2019

Thanks for sharing this most interesting of experiences and insights.

There was a time in my mid-twenties when, after reading about revelations in the media about mis-management/fraud of some charities, I pretty much stopped donating as I was so disillusioned with the whole thing.

But I realised that although the waste of all the funds was shocking, charities did do some good, so I do donate now, both to high-profile large charities and to those more local and closer to home. The millions paid to fat cat ‘charity’ bosses still does not sit well with me however.

I donate to a few via charity lotteries, ie I donate a regular sum for a chance of ‘winning’ prizes. I’ve won several prizes and after each win, I receive a letter in the post informing me of my win. I contacted said charity and asked them not to waste postage costs by sending me a letter, that they could inform me via email for free. Their response was that they did not have the ‘facility’ to inform winners by email – evidence of the manual spreadsheets you mention I fear!

In my mind, I would like to do some volunteering/charity work when I no longer need to work but as you have explained, the people ‘in charge’ will be the ones who have not been employed/employable in the kind of businesses I’ve worked in, ie ones subject to audits, regulatory processes or accountability. This would drive me mad! Hence, like @Caveman, I might go down the ‘physical’ volunteering route to try to avoid the bureaucracy!

{in·deed·a·bly} 24 March 2019 — Post author

Thanks weenie.

That is you manage to donate alongside your FIRE ambitions is highly commendable. This isn’t something that gets much discussed in the FI community, apart from those driven by a tithing obligated to whatever religious institution they may be affiliated with.

There are a large number of highly skilled people who nobly volunteer for charities once they finish working. Often times they think they’ll revel in being an extra pair of hands, rather than the person in charge. Many of these same people want flexible arrangements to accommodate regular/lengthy holidays or babysitting grandkids during the school holidays.

That lack of control grates on some people in practice, having grown accustomed to minions hopping when they said jump during their working careers.

For others the shambolic organised chaos that so often dominates decision making in non-profit organisations rubs them the wrong way, breeding discontent and dissension in the ranks.

These folks often become the troublesome “staff” that make the struggling manager’s job harder. More than a few volunteers get thanked for their contribution and told their services are no longer required.

Obviously these experiences vary greatly from one charity or manager to another, so it might be worth trying a few on for size before writing off the whole endeavour entirely!

Cashflow Cop 24 March 2019

Ah, charity. I have just these last few days discussed this with Mrs. CC because I am in the middle of completing our tax returns.

What do tax returns have anything to do with charity? It dawned on me that we earn a relatively good amount of money and are very good at investing it, but we have given little thought to donating some of it away.

That’s when I started to do a bit of research and stumbled upon something called effective altruism. Boy is that a rabbit hole. Still getting my head around it. Not quite convinced on all aspects of it yet.

Long story short. We are short on time at the moment so don’t do any volunteering work. However, we’ve decided to start donating to charity after carefully selecting one and talking to the director to make sure they align with our values and make an impact.

Perhaps it is money down the drain. Maybe it’s simply to alleviate any guilt we might have thinking about those less fortunate than us, all the while concentrating on building our own wealth.

I think the answer is the gift of time as Caveman says. Once we stop our day jobs, we will have more energy and time to physically help others.

Some personal and perhaps philosophical questions for me to continue to ponder over as we approach FI.

{in·deed·a·bly} 24 March 2019 — Post author

Thanks Cashflow Cop.

Time is certainly a valuable commodity. When used in a considered and beneficial manner, a donation of time can yield a much greater return than the “cheque book charity” that the time poor generously donate.

For example a qualified financial planner could volunteer to man a hot food caravan outside a hardware store. Or they could donate some of their hard won expertise to provide financial guidance to folks who might otherwise be unable to afford it. Anyone can do trash collection or car parking duty, but precious few are capable of providing that sort of financial guidance.

A couple of my insurance clients had long running charity schemes that gave underwriters and actuaries time off to help teach disadvantaged children in local primary schools to read. I’m a bit dubious about the effectiveness of the literacy aspects, but the sheer number of interns and graduate program entrants who benefited as children from exposure to and mentorship from the professionals donating their valuable time spoke volumes.

Something as simple as talking with a friendly professional was enough to see past the expensive suit and big salary, helping the kids to realise there was no reason why someone “like them” couldn’t one day work alongside the sharply dressed grown-up who was currently reading them the Gruffalo in silly voices.

PendleWitch 29 March 2019

While attempting to downsize my working life, I went for an interview at a nearby charity (4 days! no commuting!). Looking round, I realised I would feel guilty if I had a paid job there, what with local people all working hard to raise money for their local hospice, and a lot of that money going to salaries. I couldn’t resolve the conflict. Luckily my ongoing employers accepted my request for 3 days a week so I didn’t have to make the choice.

It does seem that the US bloggers are more vocal about their charitable giving. Due to a restricted social safety net? Blowing their own trumpet? Not sure, but I now try and be a bit more deliberate on donating, rather than just seeing a tin in the street (ah, but they don’t take cash any more either, preferring to sign you up for a direct debit). What a minefield…

{in·deed·a·bly} 29 March 2019 — Post author

I’m glad to hear you achieved the lifestyle choice, without the disruption of a new job PendleWitch. Question is, did your existing employer still expect 5 days worth of work to be performed in the three days you were available? If my experience was anything to go by, reduced availability can be a tough transition for everyone else on site to make!

I must admit I was stunned at how quickly and formulaically that charities were able to launch an aid appeal. All they needed was a location and some news coverage to raise awareness of an earthquake/flood/fire/famine. Then, like a well oiled machine, out came the stock images and moving vignettes about the plights of the unfortunate victims.

How many or few of these characters actually existed didn’t matter, it was a marketing leaver to loosen purse strings and get donations flowing.

Agreed the direct debit/recurring premium rate text message approach is off putting. The driver is the same as those used by gym memberships and mobile phone contracts: make it hard enough for people to exit and a material number will just keep paying.

PendleWitch 29 March 2019

3 days were solid most of the first year – colleagues did what they had to do. There has been a bit of time creep in the past few months though. Just do a bit on Friday, telecons that people can’t make mid week, check in in Monday to see what’s in store on Tuesday… etc. I will toughen up – thanks for the reminder!

thefirestartercouk 2 May 2019

Fascinating stuff as always indeedably!

I would love to volunteer once I am FI/Semi retired (and the kid/s are all at school so there is some free time in the day left haha) but hearing stuff like this really does put me off. The inefficiencies in my own supposedly great business work place annoy me enough!

The last few years, I have been donating via those effective altruism (as someone else pointed out above) type charities which are supposed to be really efficient at getting their sh!t done

Hopefully they don’t turn out to be a scam haha

{in·deed·a·bly} 2 May 2019 — Post author

Thanks TFS.

I think most charities help people, and most people who work/volunteer for a charity do so with genuinely good intentions. Whether that does a little good or a lot, it is a net win in most cases.

The main issue is the efficiency and effectiveness of the provision of that good. If it is costing £0.95 to deliver £1.00, when it should only be costing £0.20 then something isn’t quite right.

Individually you can’t fault many (if any) of the people involved, who are doing their best. However, when viewed from a systemic perspective there is a lot of room for improvement, yet a lot of resistance to change.

SMV 25 August 2019

I agree with much of what you’ve said. Except…you hold up the Gates Foundation as a model of what charities should be like. I worked there for a while, and they were one of the worst places I’ve been. Money was being wasted by the truckload, and almost the only thing people cared about was preserving their jobs. The foundation hired lots of expensive consultants, and the first 10 minutes of every presentation consisted of the consultant praising the Gates Foundation about the amazing job they were doing, saving the world. Even when a project had just failed miserably, having wasted millions of dollars.

It was a very, very disillusioning experience. They have a good reputation, and perhaps I experienced only the most dysfunctional department, but still…I’ve become VERY cynical about charities.

{in·deed·a·bly} 25 August 2019 — Post author

Thanks SMV. Sorry to hear your experience at the Gates Foundation was an unsatisfying one.

My point about the Gates Foundation was that their approach differed to that of many charities.

The traditional model for aid provision followed a model that involved a lot of waste and duplication. A charity or foundation would:

From what I’ve read, the Gates Foundation attempts to use existing local experts and distribution channels to minimise the duplication and corruption involved. That doesn’t guarantee their projects will be any more successful or well executed, just that less of the donations are wasted reinventing the wheel. You’ll know better than I do whether that perception reflects the reality.

Of course they may still choose the wrong problem to solve, the wrong partner to execute the solution, or treat the symptoms rather than the underlying cause of a problem.