“Underperformance compounds to substantially lower retirement balances = 13 years’ lost pay

…

Higher fees materially erode balances at retirement = 2 years’ lost pay

…

Multiple accounts reduce retirement balances = 1 years’ lost pay

…

Insurance policies erode balances for low-income workers = 2.5 years’ lost pay”

Believe it or not, those quotes aren’t sourced from a fraud trial or a report into gross negligence.

Nor were they from a consumer rights watchdog investigation into dodgy financial planning practices.

Alarmingly, it is much worse than that!

These quotes are from the recently published findings of the Australian Government’s independent research and advisory body, who were tasked with “reviewing the efficiency and competitiveness of a superannuation or pension system in its totality”.

Think about the implications of those quotes for a second.

It could be happening to you

A worker suits up and performs a days work.

Maybe they are the guys hauling rolls of carpet up to the 31st floor of Ernő Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower because the lifts are broken. Again.

Or it could be the poor unfortunates who are assembling the scaffolding up the outside of the same building… in the snow.

Perhaps they are a once starry-eyed General Practioner, who now spends their working day rationing their time into 10-minute intervals during which they are expected to correctly diagnose every known malady, while simultaneously humouring attention starved pensions and screening out frequent flyers seeking a medicinal means to cope with an ever more stressful world.

It could even be a corporate spreadsheet jockey who runs a daily gauntlet of office politics, institutional silliness, and meaningless busy work. The redeeming features being a nice salary and the fact that the work is inside, doesn’t involve heavy lifting, or dealing with the general public!

Whatever their role, the worker invests a portion of their hard-earned income in a pension fund.

Partly because saving for the future is a good idea.

Mostly because the government insists that they do so.

Poor choices compound

They select a fund that syphons off some of their savings via an entry fee on the way in.

A consistent track record is important when evaluating investments.

Unfortunately the worker has chosen a fund that consistently charges high ongoing management fees throughout its life, in return for consistent underperformance.

And for added misery, they receive will receive a kick in the backside on the way out via exit fees.

In short, it sucks to be them!

Perhaps the worker made a poor investment choice.

Or perhaps their employer made a poor choice in selecting a pension provider offering a selected range of expensive and non-performant funds.

Whatever the cause, according to the findings in the pensions report, by the time the worker retires they have potentially missed out on the equivalent of up to 13 years’ wages. To illustrate just how vast that figure is, thirteen years worth of median disposable income would more than pay for a median-priced semi-detached home in any United Kingdom region outside of London!

In Australia, where the report was written, it is compulsory for workers to contribute 9.5% of their salary into a private pension. That rate is scheduled to increase to 12% by 2025.

The mandatory savings are a good idea, and while the size of the contributions remains too low to comfortably finance the retirements of many workers, they are heading in the right direction.

The United Kingdom is pursuing a similar course, but are about 20 years behind.

Mirage

The Personal Finance blogosphere is rife with assumptions about investment yields and rates of return than an investor can expect to achieve. Yet few of them factor in the impact of fees and taxes, as everyone’s circumstances and tax affairs differ.

Are they describing an evidence based outcome?

Or simply creating a mirage of wishful thinking?

Ignoring these variables creates a danger that investors seeking easy answers may overlook those fees and taxes when performing their own calculations.

For example, how many “safe” withdrawal rate examples have you seen that explicitly account for brokerage fees and taxes in their projections?

Just as the magic of compounding enhances the returns of investors over time, that same magic will magnify the impact of fees and taxes just as effectively.

Testing the premise

I decided to validate whether the fees and charges incurred in the United Kingdom would reflect a similar outcome to the findings of the Australian pension industry review.

On the right hand side of each of the following charts I have added a “years’ pay” measure.

The unit of measurement is the United Kingdom median disposable household income, after accounting for household composition.

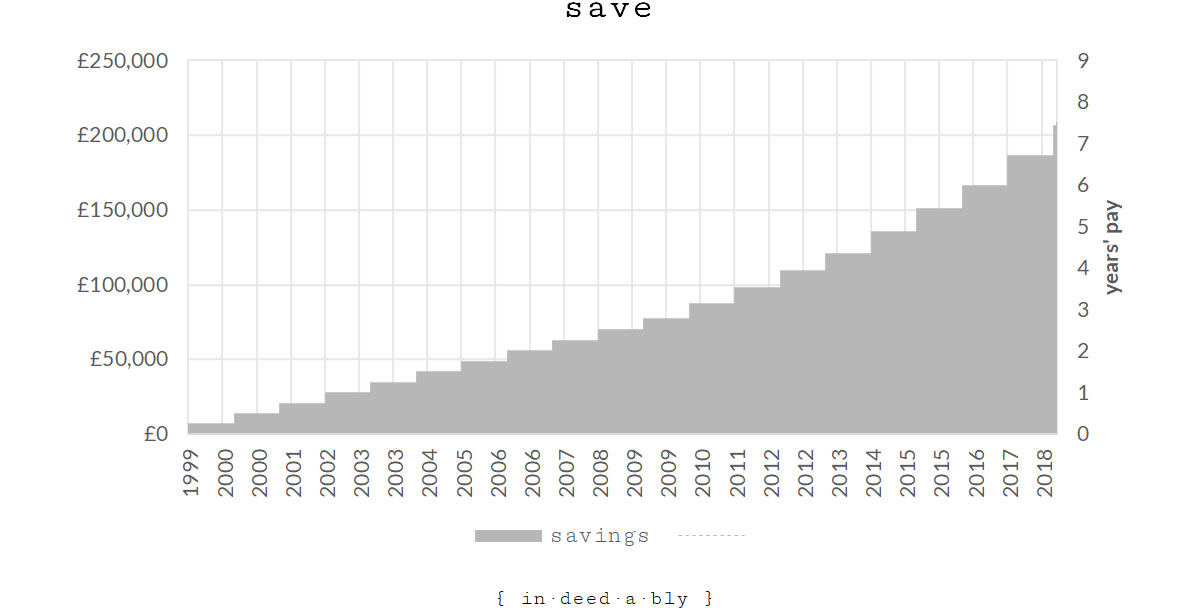

Save hard

The chart below shows the annual savings of that hypothetical worker manages to squirrel away. I have chosen the annual stocks and shares ISA limit for each year as an arbitrary annual saving amount.

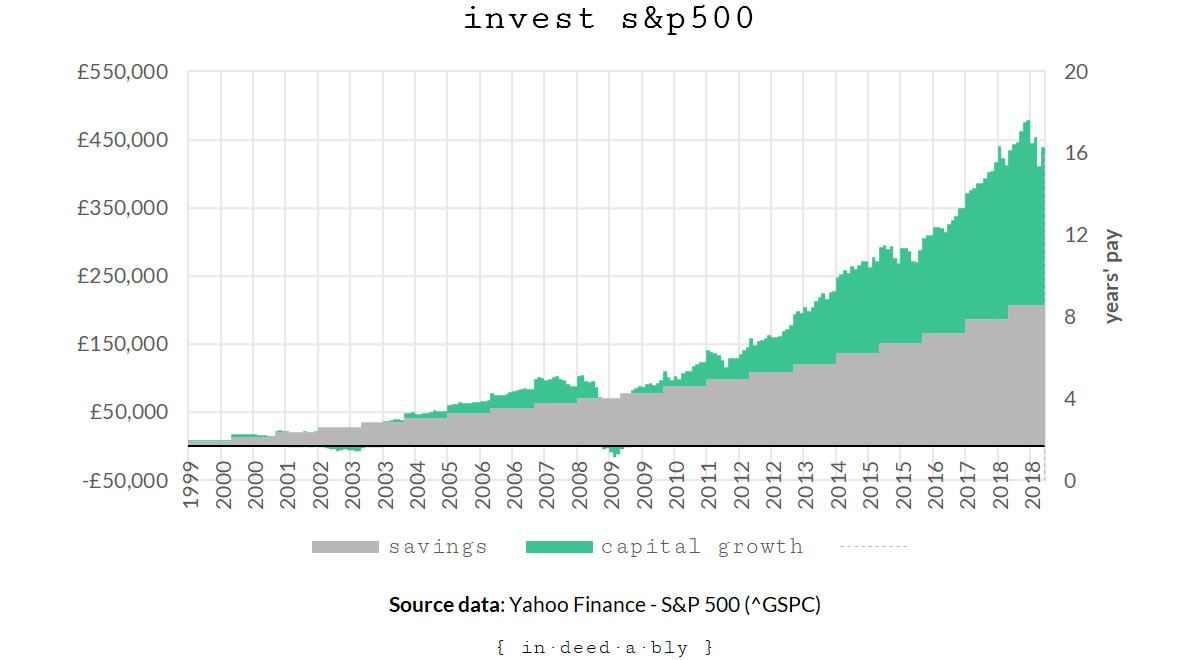

Invest wisely

They decide to invest those savings in the S&P500 index, because that is what most of the Personal Finance blogs seem to focus on.

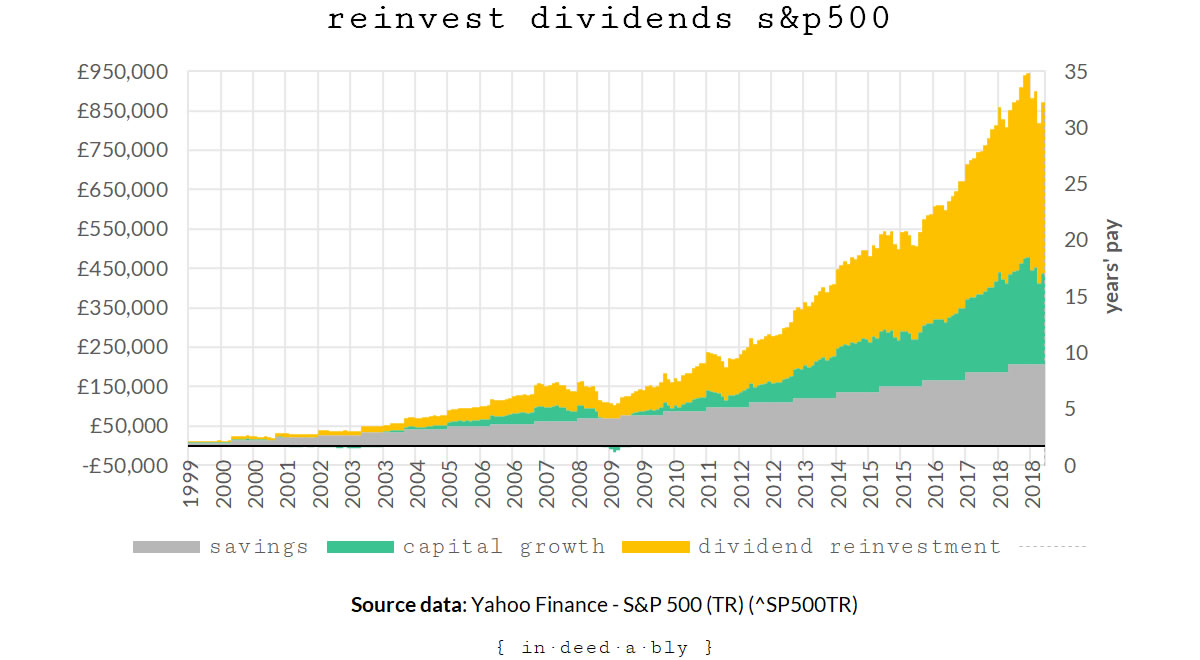

Figuring you can’t have too much of a good thing, the worker elects to reinvest all their dividends.

Wait 20 years, and according to the collective wisdom of the Personal Finance blogosphere the worker will be a millionaire or thereabouts!

Not all trackers are created equal

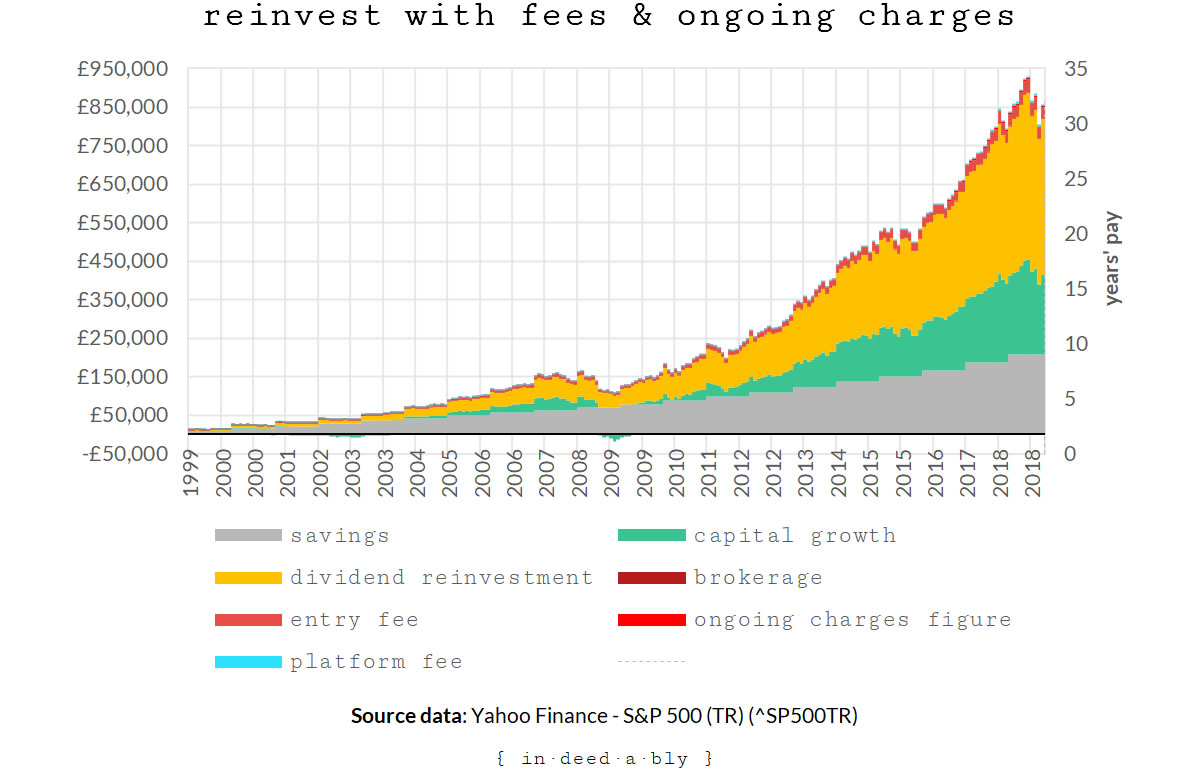

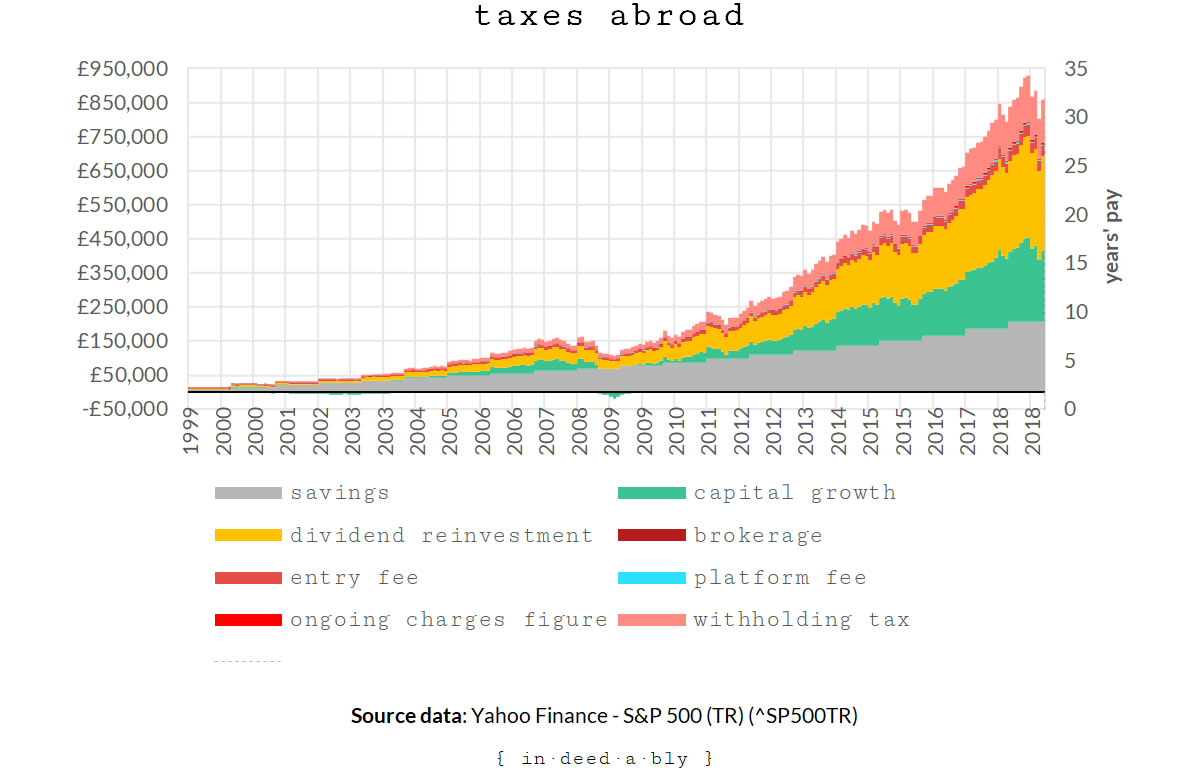

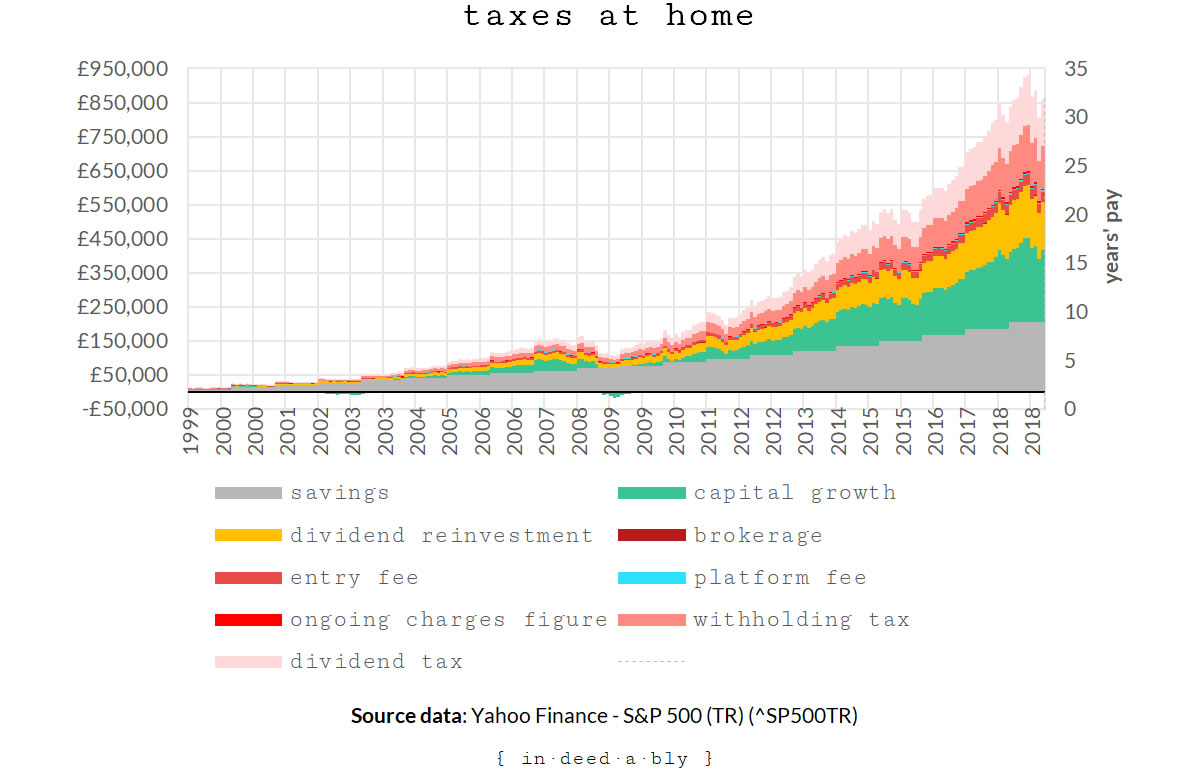

Now let’s validate those easy answers by applying some harsh truths.

Not all tracker funds are created equal. What if the worker picked a tracker fund that charged a 5% entry fee?

![]()

To add insult to injury the fund also charges a high annual ongoing charge of 1.16%.

Think about that for a second. By design the fund the worker chose to invest in will be underperforming the index by more than 6% at the end of the first year!

![]()

Platform fees and dealing charges

The worker’s stockbroker charges the worker an annual platform fee of 0.45% for the privilege of holding that investment. Some brokers also charge dealing fees.

Withholding taxes

Nobody explained to the worker about the double taxation treaty between the United States and the United Kingdom, so they had never completed a W-8BEN form that relieves them of the obligation to pay the 30% withholding tax which the United States levies on foreign investors.

Dividend tax

The worker didn’t know about ISAs and didn’t understand about pensions, so they bought the fund using a taxable brokerage account.

Unsurprisingly the British tax authorities wants a cut of those dividends too. The tax man doesn’t care that the worker reinvested them, tax is payable regardless. For the sake of simplicity we will assume the worker was a higher rate taxpayer, liable for 32.5% tax on dividend income.

This harsh dose of reality paints a very different outcome to the rose coloured perspective we so often read about. A naïve investor blindly following a simplified narrative using taxable accounts is easily led astray.

If an investor were to do everything wrong, fees and taxes could see them forgo investment returns worth up to 10 years’ pay!

There has to be a better way!

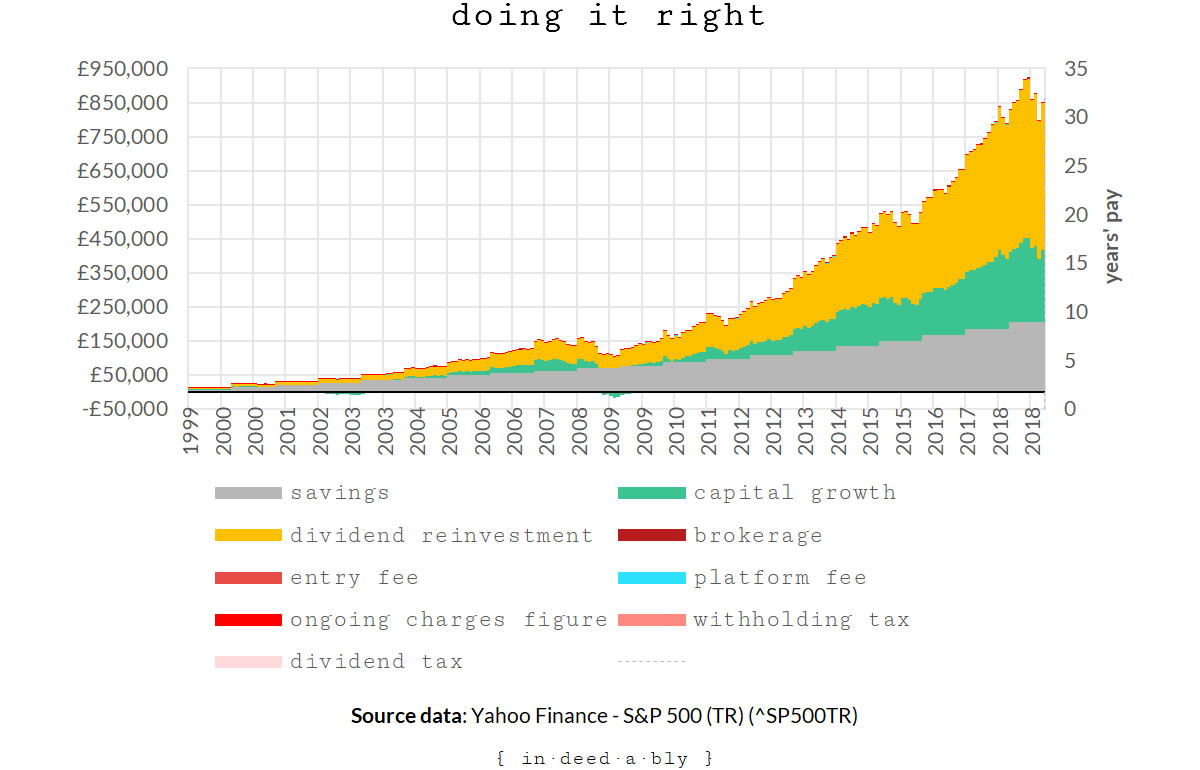

Fortunately there are several things the worker can do to improve their situation.

- They can complete the US tax form, to remove the unnecessary burden of withholding taxes.

- The expensive and underperforming by design fund can be substituted for a better value alternative.

- Their shareholding could be transferred to a more reasonably priced brokerage platform.

- Making use of tax-advantaged accounts could defer (pensions) or eliminate (ISAs) the UK taxes due on capital gains and dividends.

When combined, these simple steps produce a dramatically improved outcome!

The takeaway here is that making poor investment choices can literally cost you years of your life, requiring you to sell your time for longer than would otherwise have been necessary.

Engineered to fail

These actions are relatively straight forward in a brokerage account entirely selected and managed by the worker.

Unfortunately many workers rely upon their employer to choose their pension platform and fund selection.

Often these choices are suboptimal.

Expensive.

Offering a poor selection.

Of only bad options.

The hypothetical worker used in this example has been spectacularly unfortunate in their investment choices, piling mistake upon mistake.

That would be disappointing had the worker personally made all those choices.

However what if the employer had chosen the brokerage platform and the expensive fund? It is hardly unprecedented for employees of fund operators to have their fund selections restricted to only expensive operated by the firm.

This unfortunate outcome isn’t as farfetched as it may at first sound.

How does the shelf packer at your local supermarket discover the finer points of the US tax code?

Is your immigrant bus driver able to sufficiently decipher the broker comparison tables, to determine which platform is the most cost-effective to host their pension fund?

Would the teachers assistant at your toddler’s nursery meaningfully be able to compare and contrast the fund OCF fees, adjusting for entry and exit charges?

Regardless of their financial literacy levels, all of these people in your local community now have part of their incomes invested into pensions by default.

Design for success

Employers should owe a duty of care to their employees to ensure they have the most performant and cost-effective pension options available to them.

But they don’t.

The government should mandate that default pension options are strong, stable, low-fee index trackers without entrance or exit fees.

But they don’t.

Stockbrokers should offer free of charge investment hosting on their brokerage platforms, in the same way that banks offer free current accounts. They already make more than enough money on dealing fees, fund management charges, and money market interest on cash holdings.

But they don’t.

The generously tax-advantaged pension system operating in the United Kingdom is ostensibly designed to ease the state pension burden by helping individuals become (at least partially) self-supporting in retirement.

That is a sound policy goal, but this outcome will only be realised if the system is engineered to succeed.

The alternative results in a taxpayer-funded subsidy to the financial services industry, who are free to gorge themselves on compulsory yet ill-directed pension contributions.

There is a lot that can be learned from the Australian experience.

The good, such as the periodically increasing mandatory contributions to pension accounts.

And the bad, such as the astonishing greed and malfeasance demonstrated within their local financial services industry, while the regulators navel-gazed and dithered.

References

- AJ Bell (2019), ‘Stocks and Shares ISA‘

- BNY Mellon (2019), ‘BNY Mellon S&P 500 Index Tracker USD A (Acc)‘

- Hargreaves Lansdown (2019), ‘Share dealing service‘

- HM Revenue & Customs (2019), ‘Tax on dividends‘

- Internal Revenue Service (2019), ‘About Form W-8 BEN-E. Certificate of Entities Status of Beneficial Owner for United States Tax Withholding and Reporting (Entities)‘

- Monevator (2018), ‘Compare the UK’s cheapest online brokers‘

- Office of National Statistics (2018), ‘Household disposable income and inequality in the UK: financial year ending 2017‘

- Office of National Statistics (2018), ‘Median house prices for administrative geographies: HPSSA dataset 9‘

- Powers, T. (2018), ‘Employer super contributions: SG rate 9.5% for 2018/2019 year’, SuperGuide

- The Productivity Commission (2018), ‘Superannuation:Assessing Efficiency and Competitiveness’

- Vanguard (2019), ‘S&P 500 UCITS ETF (USD) Distributing (VUSA)‘

- Weathers, R. (2019), ‘United States: Corporate – Withholding taxes’, PWC

- Yahoo Finance (2019), ‘S&P 500 (^GSPC)‘

- Yahoo Finance (2019), ‘S&P 500 (TR) (^SP500TR)‘

youngfiguy 3 February 2019

Really interesting post (at least for a pensions geek like me).

If it makes you feel better, from those I’ve spoken to in the pensions industry the lessons from Australia are being listened to and thought about very carefully.

One benefit we’ve already seen is that auto enrolment has not led to bank dominated pensions sucking money from people. That means we have avoided a great deal of the pain felt over in Aus.

In terms of fees, the UK does pretty well comparatively. We work out cheaper than Aus (and some other countries).

There is talk of lowering the fee cap from 0.75% as well. Though I think the earliest we can hope for a reduction is 2020.

The big question a lot of us are really struggling to answer is how to improve engagement (or whether it’s worth the effort at all to power engagement). According to the TPR 98% of people are in the default fund. I understand only c.15% of members register with one of the largest master trust schemes in the UK.

Well designed default funds work for the vast majority of people who aren’t interested or able to appropriately work out which investment option is right for them.

I think for the most part default funds in the large master trust schemes are well put together and the trustees take their fiduciary duties seriously. I’d prefer more member representation with these schemes, but it doesn’t look like that’s going to happen.

{in·deed·a·bly} 3 February 2019 — Post author

Thanks for sharing those insights into the pension industry Mr YFG.

It will be fascinating tomorrow to see what findings in the final report from the Australian Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry contain.

Pensions are tax advantaged accounts, with a bunch of compliance paperwork associated with them. It would be possible to keep track of the pension holders via the HMRC. Whether that possibility is a practical reality is open to debate, but linking pensions to a government gateway id would be involve less friction than the current arrangements where every pension provider duplicates effort attempting (and often failing) to keep track of their pension holders.

Providing the default choice is a good option, that won’t see the punters getting fleeced, then engagement probably doesn’t matter. Few would have cause for complaint if they were steered into a VWRL style low cost global index tracker.