Many years ago I would sit near the back of a vast lecture theatre and listen to some of the great minds of Economics reluctantly attempt to teach Economics 101 to a vast sea of uncomprehending faces.

The lecturers seldom wanted to be there.

Teaching hours were viewed as an unwelcome distraction from more worthy uses of their time. Academic research. Publish or perish. Subverting or suppressing opposing views as if their very livelihood depended upon it. Because it did!

Many of the students didn’t want to be there.

Their youthful fantasies of helping cure society’s problems, learning to steer corporate giants, writing government policy, or understanding “what happens next” hitting a roadblock of impenetrable jargon and vast oversimplification.

The elasticity of demand. Equilibrium. Indifference curves. Marginal propensity to save. Oligopolies.

Yet Economics 101 was a mandatory subject for all financially or politically orientated degrees, so here sat nearly one thousand bored students.

Sleeping with their eyes open.

Desperately hoping to learn by osmosis as economic theory was delivered in a mind-numbing monotone drone, by lecturers displaying all the enthusiasm of somebody undergoing a tax audit.

A sudden frisson of excitement rippled along the row of seats around me.

The lecturer had said “ceteris paribus”. Again!

A Latin phrase used by economists that roughly translates as “all other things being equal”, which essentially means that if we ignore all the other possible contributors to a change, then it must have been triggered by the variable being currently examined.

High fives and grins were exchanged.

In the third week of lectures, one of the more astute students had realised we were all in deep trouble. Attendance was starting to wane. Tutorial assignments weren’t being submitted. The whole class was in danger of failing.

So she invented a drinking game that required players to attend lectures and pay attention. Every time a lecturer said a variant of “all other things being equal”, the students who noticed could have a drink in the bar after the two-hour-long lecture.

Anyone who has studied economics will tell you that “ceteris paribus” gets said alarmingly often!

Attendance improved.

Students learned economic theory.

Wednesday nights in the university bar quickly became the social highlight of the week, as students came together to celebrate “ceteris paribus”.

More than half the class graduated Economics 101, equipped for successful white-collar careers with a reasonable grasp of economic theory and high-functioning alcoholism.

All other things being equal?

Earlier this week I was on a video conference with a colleague in Boston. For reasons I didn’t entirely understand, he had dialled in from a park bench on Boston Common looking towards the gazebo.

Midway through a conversation about market segmentation and demographics, a homeless guy suddenly loomed over my colleague’s shoulder and photobombed the video conference. He articulately informed us all that at the end of 2019 the first of the Millennial generation will become eligible for the protections of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act. Then he vanished off-camera as quickly as he had appeared.

My colleague goldfished for a moment. The pronouncement had been as random as it was unexpected.

“I think that is the Act which was supposed to prevent employers from discriminating based upon age when making hiring or firing decisions,” he stammered.

Then he paused. Brow furrowing.

“Though I’m pretty sure it actually allows employers to use age discrimination, providing it is in favour of folks aged 40 and over.”

It was our turn to pause. Pondering the irony of legislation that prevented discrimination against one class of people, while simultaneously enshrining into law the ability to discriminate against another class in exactly the same way.

All other things may be equal, but some people are more equal than others.

Millennials turn 40

If the homeless guy was correct, then the much-maligned Millennial generation was about to start turning 40.

All grown up.

Careers topped out.

Childhood dreams faded.

Responsibilities mounting.

For as long as I can remember there have been news stories gnashing teeth and wringing hands about a “housing crisis”. First home buyers priced out of the property market. Tens of thousands more houses needed to be built every year. Homelessness on the rise.

Property, the wealth creation engine of previous generations, was firmly out of reach of young people.

That has become an accepted narrative.

Advanced by rent-seeking estate agents, home builders, and mortgage lenders.

Fanned by vote-buying politicians, who want to be seen to be doing something in the form of ineffective handouts and subsidies.

However, as the pharmaceutical industry or any long term consultant can tell you, there is far more money to be made by persisting a problem than solving it.

That got me thinking: is that narrative actually true?

One thing that always troubled me about economic theory was that ceteris paribus assumption: all other things are equal. It was fine for a theoretical demonstration of a concept in a textbook, but when it comes to real-life when has anything ever been equal?

I decided to dig into the numbers to validate whether the narrative reflected reality.

Affordability

First I looked into affordability.

For every potential buyer, there is a price ceiling that they simply cannot exceed. Simplistically speaking, this is the amount they can contribute themselves plus the amount they can borrow.

That said, buyers would be unwise to fully extend themselves as it leaves them vulnerable to interest rate shocks and facing the risk of negative equity should property prices fall. Taking out a big mortgage is a bit like eating a whole pizza: just because we can doesn’t mean we should.

One of the main factors that determine how much a mortgage lender is willing to offer is earnings multiple.

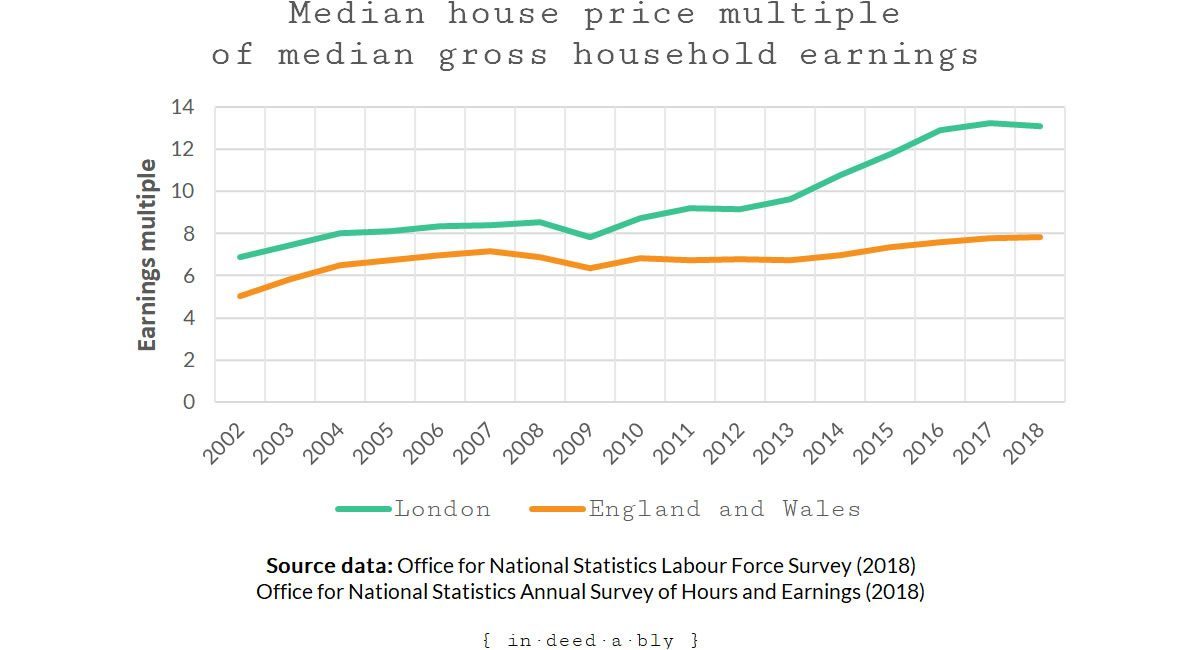

Plotting the ratio of median house prices to median gross household earnings over time reveals property price growth has significantly outpaced wages growth. Especially in London.

The ONS statistics only go back to 2002, which is a small sample size that does not contain many laps through the property cycle. I hunted around for other datasets that might help explore this story over a longer time series.

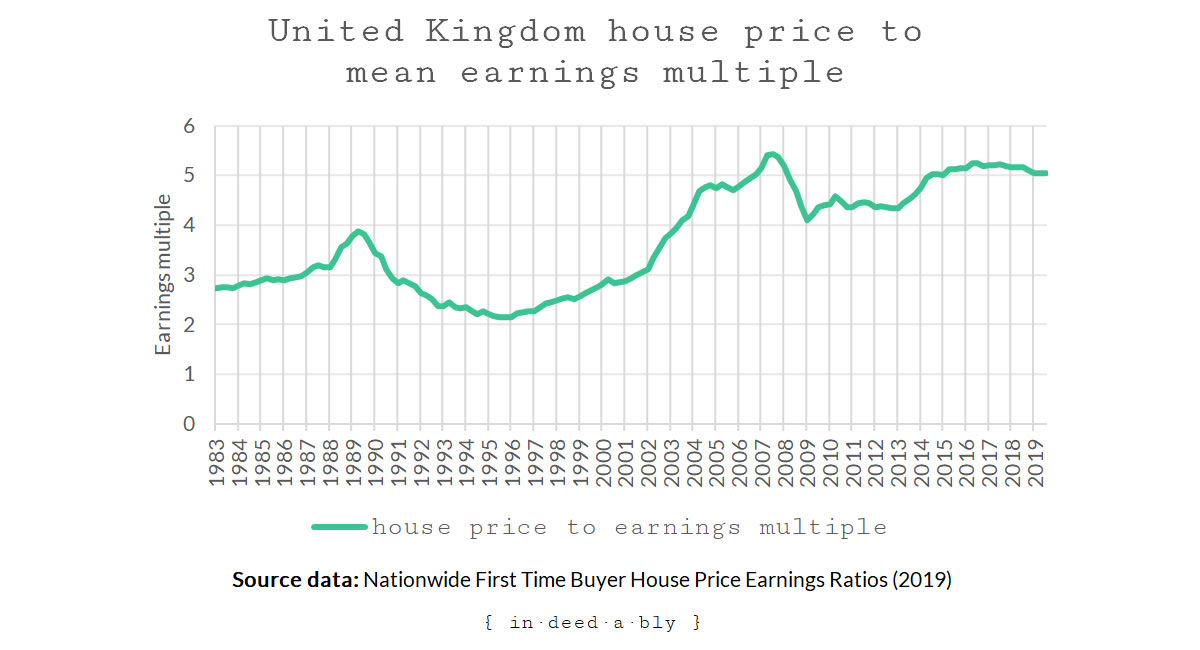

Nationwide publishes a home affordability index going back to the early 1980s. The story told is subtly different, as Nationwide uses the house prices paid by buyers ticking the “first home buyer” box on their mortgage application. This means the data excludes remortgages, people moving house, or purchasing investment properties… in other words the majority of property transactions. There is an inherent sampling bias in the property price element, as first home buyers tend to purchase at the cheaper end of the property price spectrum.

On the earnings front, Nationwide chose to use mean individual earnings as the metric to track. For this dataset, the mean tends to be higher than the median, as for every high earning investment banker there are dozens of folks earning minimum wage flipping burgers or stacking shelves. Individual earnings will also differ from gross household earnings, where a household contains multiple income earners.

Now that we understand those important differences, we can see the Nationwide data series tells a broadly similar affordability story. Over time, directly owned residential property as an asset class has become relatively more expensive.

Homeownership

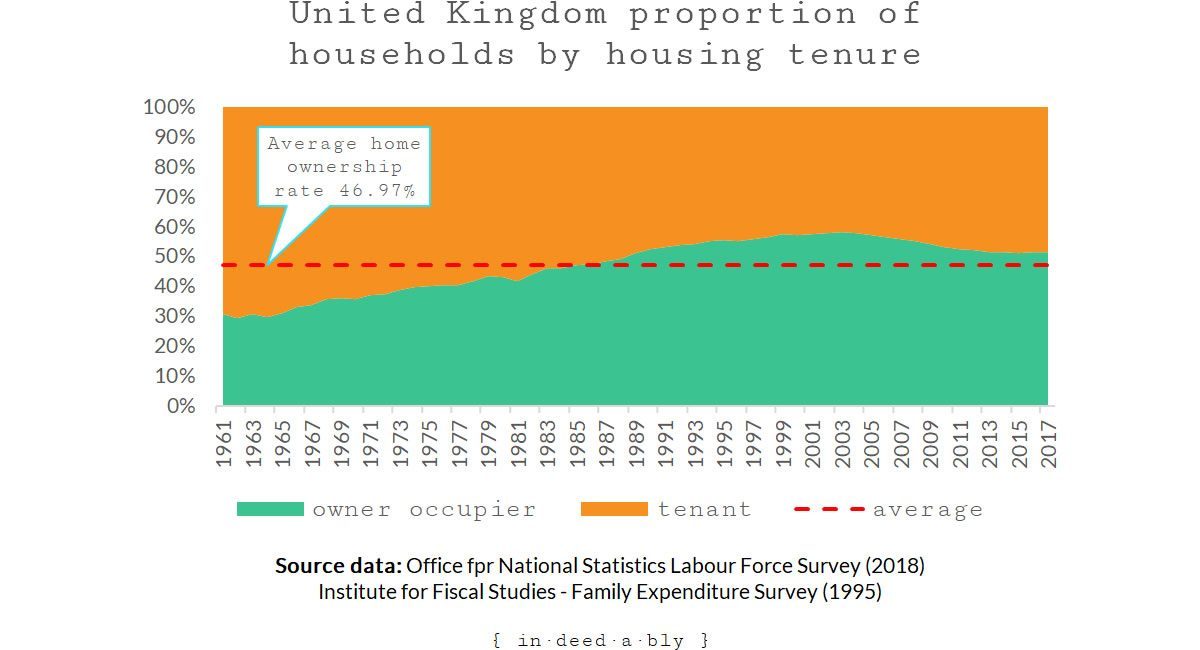

Next, I looked at homeownership rates. If the narrative was correct, then houses had been getting ever more expensive as to be out of reach of median earners. Therefore we should see a corresponding drop in the proportion of the population who are homeowners. This would be a trailing trend, and a slow-moving one, as people tend to buy and sell their homes infrequently.

The data appears to tell a different story, with homeownership rates steadily increasing even as prices climbed. How could this be? Were people simply paying what it cost to buy a house, and cutting spending elsewhere to offset those costs? Or was it a byproduct of an ageing population?

I wanted to explore these questions further, to understand what was going on.

The Ministry of Housing publishes a dataset breaking down homeownership by age band. As the earnings multiple required to purchase a house climbed, the corresponding rate of homeownership in the younger age bands has fallen.

It is taking people longer to get on the property ladder than in previous generations. That delay has a double whammy effect of having to pay higher prices, while simultaneously missing out on the wealth generated by those same rising property prices.

The chart also shows that only those aged 35 and above are more likely than not to own their own home.

I looked into the proportion of household expenditure devoted to housing costs. The short version: keeping a roof over their heads consumed 9% of household expenditures in 1957, today it requires 18%.

Think about that for a moment.

We are currently experiencing some of the lowest interest rates in recorded history, and have been doing so for the last decade. Yet today housing costs comprise nearly 20% of household expenditures. More than a few folks are going to experience a whole world of pain and cash flow distress whenever interest rates revert to the long term historical average.

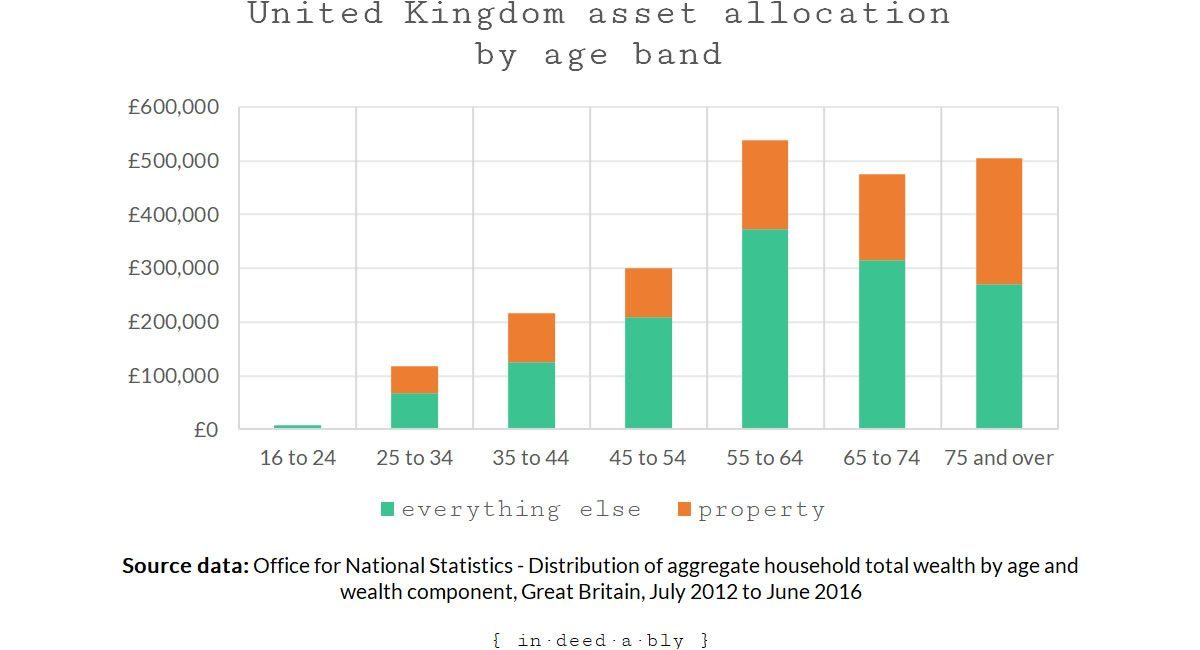

The final chart highlights the role that property plays in wealth creation. By the time folks are reaching state pension age, their home typically accounts for around one-third of their wealth.

Wealth inequality

Trawling through all this data has highlighted a significant wealth inequality problem brewing. One that is already well underway.

If young people are unable to afford properties, then they won’t buy them. Instead, they will complain. Find somewhere to rent. Learn to live with disappointment.

But the story doesn’t end there.

By not buying property, those young people miss out on the opportunity to deploy the most commonly used form of leverage to increase their wealth: a household mortgage. Using other people’s money to boost their own wealth.

Missing out on the opportunity to own their own home also means missing out on one of the most tax-advantaged asset classes available in Britain. Over the long term owner-occupied homes tend to appreciate in value. That growth is free from capital gains tax, unlike other asset classes such as bonds, investment property, and shares when held in taxable accounts.

Therefore, over the long term, their net worth will likely be comparably smaller as a result.

Eventually, most homeowners pay off their mortgage. At that point their cost of living greatly reduces, providing the option to enjoy the luxury of choice. Change to a lower-paying but more fulfilling career. Retire, partly or in full. Study. Travel.

Tenants don’t enjoy that same luxury. Not owning a home means rental bills that only cease once they do.

Later in life, when their ability to work diminishes, they may experience cashflow pressures that a homeowner may not.

Some folks will pursue alternative forms of investment. Perhaps maximising their tax-free ISA allowance or using tax-advantaged pensions to invest in shares or managed funds.

A few will deploy leverage in other forms, for example margin lending.

However, the level of financial literacy required presents a barrier to entry to financial investments.

Many will squirrel money away in savings accounts.

Others will simply consume it all.

Homeownership is a lifestyle choice at least as much as it is a financial one.

Homeownership is a privilege rather than a right.

Unfortunately, high earnings multiples mean there is a risk that homeownership becomes available only to the privileged. Over the long term that will contribute to wealth inequality. Those who don’t own their own homes feeling left behind by those who do.

The underlying causes are basic supply and demand, as they taught us in Economics 101. When there are more buyers than sellers, then prices will rise. They will continue to rise until there are no more buyers. No amount of subsidy or handouts to first-time buyers will change that simple equation.

All other things being equal, it does appear that Millennials have a legitimate complaint about the tough financial hand they were dealt.

References

- Belfield, C., Chandler, D., and Joyce, R. (2015), ‘Housing: Trends in Prices, Costs and Tenure’, The Institute for Fiscal Studies

- Heathfield, S. M. (2019), ‘What Is Age Discrimination in the Workplace?’, The Balance Careers

- Liberto, D. (2019), ‘Ceteris Paribus’, Investopedia

- Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (2012), ‘English Housing Survey data on owner occupiers, recent first time buyers and second homes‘

- Nationwide (2019), ‘First Time Buyer House Price Earnings Ratios‘

- Office for National Statistics (2018), ‘Distribution of aggregate household total wealth by age and wealth component, Great Britain, July 2012 to June 2016‘

- Office for National Statistics (2019), ‘Family spending in the UK: April 2017 to March 2018‘

- Office for National Statistics (2015), ‘Housing and home ownership in the UK‘

- Office for National Statistics (2019), ‘House price to residence-based earnings ratio‘

- Resolution Foundation (2019), ‘Home ownership in the UK‘

- Tetlow, G. (2018), ‘Rising burden of housing costs shown by 60-year UK spending survey’, Financial Times

- U.S. Department of Labor (2019), ‘Age Discrimination‘

GentlemansFamilyFinances 15 November 2019

very good article.

I attended economics courses in engineering school. I really enjoyed it and it got me onto reading economics books to understand about big trends in the world.

That was back in 2003 and even then it was clear that in the UK there would be a shortage of housing and house price inflation (lack of building, smaller household units, immigration, life-expectancy…) also that DB pensions would be a thing of the past, Interest Rates would continue to fall and global growth would be fueled by India/China and also that assets would fare better than cash (inflation). Finally, Millennials were going to be screwed!

Armed with all of these facts and my economics skills – I used this information to better my situation.

Maybe I should have spent my student loan on a spreadbetting the markets in 2003 (I’d be rich!) or bought more houses than just one flat when I started working – but I’m not naturally a dogmatist.

Ceteris Parisbus – I’m lucky that economics was on a Wednesday afternoon instead of a Friday morning after a heavy night’s drinking – as an old Millennial, I’ve used my education to hedge against the headwinds of change – most of my cohort are not as lucky.

{in·deed·a·bly} 15 November 2019 — Post author

Thanks GFF.

You raise an interesting misconception. Is there really a shortage of housing? Home builders would say yes, but their business model relies on ever building more.

Or is the problem really a concentration of ownership?

While there are plenty of unfortunate folks who find themselves homeless, I don’t think there is widespread difficulties obtaining a home to rent. Finding somewhere to buy, that is affordable, now that is a different story!

GentlemansFamilyFinances 15 November 2019

housing is a massive problem in the UK.

Anyway you look at it.

Many of my boomer relatives own multiple properties and complain that their kids can’t get on the ladder.

government policy protects homeowners massively – inheritance tax, no CGT, low council taxes and so on.

On a conceptual level – the fact that BTL stands for BUY to let tells you everything you need to know about the problem. If millions were actually involved in BUILD to let then you might have a solution to the misallocation of housing in the UK.

Sadly, for millions of millennials and beyond, if you don’t get Housing Benefit (the £27b/y landlord subsidy), didn’t get help from BOMAD or didn’t buy at the right time – property has impoverished you – to the point where you’ll be paying for the retirement (and cruises) of boomers until they pop their clogs.

{in·deed·a·bly} 15 November 2019 — Post author

Exactly. A distribution problem rather than a supply problem.

Steveark 15 November 2019

Your housing costs in the UK are frightening. By comparison I calculated the ratio of median income divided into median house price for my rural southern state in the US and it is only 2.6. That’s less than 1/3 of the UK and 1/4 of the London figures.

{in·deed·a·bly} 15 November 2019 — Post author

There is a lot to be said for living somewhere quiet, affordable and offering a great standard of living.

It often makes the difference between achieving financial freedom and a lifetime of tilting at windmills.

That said, the jobs offering big money are often in the big cities. Supply and demand creating a vicious circle.

broadbandylegs 16 November 2019

Thanks for another excellent post. I’m in Scotland, so maybe this is not such an extreme problem as in the SE.

I recall conversations about rising house prices in the 80s. Interest rates were sky high then, so increasing prices seemed like payback for punishing monthly payments. But even then, we were asking how our kids would be able to buy if things continued like that.

Contemporary government policies like Right to Buy and the hobbling of social housing building haven’t exactly helped either.

So not a new problem – chickens coming home to roost?

But maybe the outlook’s not too bleak.

On the one hand – it’s more difficult to buy property at a young age.

On the other, it is likely that wealth will be transferred to that generation in the form of larger inheritances – BUT – at an older age for the recipient.

And, If you accept that, overall, wealth continues to increase, maybe that generation will still end up better off than their parents?

Time will tell I guess.

And yes, there is something (plenty!) to be said for living somewhere affordable, offering better balance 🙂

{in·deed·a·bly} 16 November 2019 — Post author

Thanks broadbandylegs.

You raise an interesting point about potentially receiving inheritance later in life. The sudden receipt of a paid off home or equivalent financial windfall could potentially be life changing for many. Instant financial independence.

It will likely come too late in life to materially help the deceased’s own children, but if it were to skip a generation then it could certainly help their grandchildren.

Of course that is assuming it hasn’t first been consumed by nursing home fees and pensioner cruise/coach tours that specialise in “spend the kid’s inheritance” style package holidays!

FB 16 November 2019

There seems no doubt that housing is becoming increasingly expensive, but you’re falling into the usual statistical trap of using multiples based on some measure of ‘average’ earnings against ‘average’ house prices.

Personally, I’ve always had well above-average earnings yet the properties I’ve bought over time have all cost way under the prevailing ‘average’ price, even when compared to the local rather than national markets.

I’ve never been comfortable leveraging what I thought I could afford to the very maximum in pursuit of what I consider somewhere to live rather than an appreciating asset to be milked in the future. And of course, with the benefit of hindsight I can see how this was a huge financial mistake, but no-one knows at the time how either their earnings or house prices will pan out in the future.

Perhaps a much more useful indicator would be peoples’ actual earnings against the actual price they paid, but I suppose only the individuals themselves and the mortgage companies would know this.

{in·deed·a·bly} 16 November 2019 — Post author

Thanks for reading FB.

As you observe, no two experiences will be exactly the same. The median (not average) figures I used represent the middle person of the population, both in terms of earnings and property values. The takeaway should be that property has gotten steadily harder to afford over time for that middle person in the population.

The smart money will have emulated SteveArk’s wise approach of high earnings and low property prices. It sounds like you have followed a similar path.

Meanwhile those who flock to the City chasing investment banking money may do ok providing they are actually the investment bankers, but will certainly struggle if they are the security guards, cleaners, or administrative staff.

I’m not sure I understand what the indicator you propose would be able to tell us. It would match a static historical sunk cost (the actual property price paid) against a dynamic and generally rising earnings number. Over time the indicator would typically show an ever lower multiple, as the numerator (historical property price) remained constant while the denominator (current earnings) grows.

Felice Pazzo 16 November 2019

Interesting article, Indeedably, and as as a non house-owning baby-boomer, something that I have thought about. I would watch-out for changes in Government policy as the demographics of the haves and the have-not voters changes over time – already I see the youth taking a keener interest in the power of the ballot box. I also wonder whether we will see parallels with the likes of poorer European countries where the young go abroad for better wage-earning opportunities, and only come back (if at all) when they have made their fortunes. For myself, I think it is increasingly likely that I will make my home abroad where I can leverage the value of the UK pound … as someone once said ‘go where you are treated best’, and I’m not sure whether that is the UK for our youth!

{in·deed·a·bly} 16 November 2019 — Post author

Thanks Felice.

You raise some interesting points.

You’re right about the politicians being keenly aware of voter demographics. That is why it is unlikely we will see a value based land tax or the introduction of capital gains tax over owner-occupied housing any time soon. Old folks vote!

I think everyone should try living abroad at some stage in their lives. This broadens horizons, and helps to demonstrate that people are pretty much the same the world over. By doing so the individual either discovers somewhere they like living more, or appreciates how good they had it back home.

Either way they are richer for the experience.

Living abroad also helps to see how our home country is perceived by outsiders, once we escape the bubble of local politicians, media influences, and opinion makers. For example, it is equal parts fascinating and frustrating to realise just how selective and biased domestic news coverage actually is. Something we don’t tend to notice while we reside within the bubble.

ZXSpectrum48k 17 November 2019

A supply-demand imbalance is one cause but it’s also a side effect of the process of money creation in a modern fiat currency system. In such a system, there is no constraint on the creation of money, only a constraint on the price of money. All money is debt, with around 97% of money is created by commercial banks during the loan creation process (as a side note I still find it odd that many economics grads haven’t been told that fractional reserve banking is a myth). So those with negative net wealth can keep giving to those with positive wealth by going further into debt (creating more money).

To make this sustainable, you need to be able to service that debt and that requires lower interest rates. Fortunately, inflation has been falling since the late 1980s, and this has allowed interest rates to fall. Lower inflation and lower interest rates are very good for asset prices, making the rich even richer and forcing the poor to buy or rent those assets (a.k.a. houses) at ever higher prices. This causes them to go into even more debt. Low inflation also means that the principal is being deflated away at a much slower rate.

To counter this, government should be offsetting house price appreciation via other economic and regulatory channels. The problem is that the boomer majority has no incentive to do this. Moreover, the UK has always had a culture of rentier capitalism, unlike say the US where entrepreneurial capitalism is more common. Originally, that was extracting rents from the colonies but we’re now extracting those rents from ourselves across generational lines.

We’re in a post-scarcity world for human labour. Yet we demand ever higher wages in the UK, despite the fact that most individuals are no more skilled than their EM counterparts. Our focus should be on reducing the cost of living, of which housing is a major part. Yet, the older generation refuse to vote for change. We’re hooked on rentier capitalism and we refuse to go to rehab.

{in·deed·a·bly} 17 November 2019 — Post author

Thanks for sharing your thoughts ZXSpectrum48k.

I think you’re right that the options required to untangle the current mess are not politically viable to pursue given the current demographics of the electorate.

On the wages front, a global economy will force that cost of living adjustment on the UK whether we’re willing to accept it or not.

Odysseus 18 November 2019

Hi Indeedably,

Very interesting article. Thank you.

I wrote a post couple weeks ago showing the homeownership in EU+UK during the last 10 years and as far as I could see most of the countries has a decline on the numbers. You can have a look there

All the best.

Cheers!

{in·deed·a·bly} 18 November 2019 — Post author

Thanks Odysseus.

The ECB recently published an interesting look at housing affordability trends across Europe over the last ~20 years.

The story it told was a rapid decline in affordability in the early 2000s that came to an abrupt halt with the 2008 Financial Crisis. What followed was nearly 10 years worth of improvement in affordability which has only recently started to diminish once more.

Digging into the aggregate figure revealed many different stories at the individual country level without a consistent narrative, as the combination of local attitudes and domestic policies differ markedly between locales. The figures in your post appear to tell a similar story.

References

Stuart Andrews 25 November 2019

Very interesting article, I am far from being Father Time but it was different in earlier years in other respects.

In the 1957 example you note the share of income spent on housing was 9% of income against 18% of income. We are asked to think about it… my immediate thought was the cost of food is much lower now than when I was a child. The same ONS date from 1957 shows the share of household income spent on food was 33% ( and now 16%) so food and housing was 42% and now 34%…

It’s a crude comparison comparing 1957 and now because of other huge changes that have occurred.

1957 was before my time( just) but the standard of living was massively lower to now, but expectations were different, knowledge of other people’s lives lower, job security was generally higher.

The big issue now for most buyers is the size of deposits rather than affordability tests but the deposit requirements are those set by regulations rather than the market.

It seems almost unbelievable now that I bought a house in 1983 on a whim, going into a building society getting an approval in principle for 0% deposit mortgage on the spot, ringing a mate I was already sharing with and saying how about buying a house together ? Viewing a house in the afternoon and it was all done and dusted in just days moving in about 6 weeks later.

At that time we had the deposit insurance scheme, resented then but the building society were covered against the first 25% of any decline in the price in the event of repossession, perhaps a return to that system might help ?

Funnily enough my experience of property has been profitable but not dramatically so. My investment assets are around 5x the value of my house.

It is clear my property owning route has been easier than that of millennials but other aspects of life are much better now.

It’s only the exuberance and lack of fear at 19 that allows you to take a free train ticket and £50 from the job centre, to take a train from a depressed regional area of Britain and set off for the smoke with just a suitcase. Without family where I was going or where I went to, it was not easy, my point is that it’s always been tough for young people from less well off backgrounds, housing is an issue but a lack of jobs in the late 70’s was a major problem too.

I only have one set of experiences and that clearly clouds my viewpoint !

Access to decent housing and jobs are equally important to young people, it’s a balance between the two that is important and public policy should be directed to both areas.

{in·deed·a·bly} 25 November 2019 — Post author

Thanks Stuart.

You’re correct in observing any comparison between eras can only be a rough approximation. Changes are many, complex, and interlinked.

Housing and taxes are most household’s two largest areas of expenditure, so it was an interesting exercise to consider how the housing element had changed relatively.

Jobs are indeed key. In the 70s there was high unemployment. Today there is virtually full employment. Yet today I suspect there is also vast amounts of underemployment that the methodology currently used to prepare the official figures struggles to reflect.