Feeling like I had walked barefoot across a sea of Lego, I hobbled the final few steps towards an ancient stone sitting beside the path. With a mighty sigh of relief, I extracted something small yet exquisitely painful from inside my boot. Why the hiking gods had chosen to punish me in such a way remains a mystery, yet punish me they had.

The stone I leaned against resembled what the ancient Romans might have called an obelisk. A milestone, indicating the distance to a given destination. One of a series of permanent progress markers, impervious to the ravages of time, weather, or the ever-changing whims of the traveller.

It occurred to me that without knowledge of that destination, a milestone lacks context or meaning.

Becoming nothing more than an arbitrarily positioned rock upon which somebody has graffitied a number. Their appearance or absence reduced to a somewhat random “life happens” event. Offering no help determining whether our motion is progressing us closer to or diverting us away from our goals.

Which is unsurprising. That is precisely how many major milestone life events feel in the moment.

Notable.

Significant.

Worthy of celebration, or commiseration.

Births. Deaths. Graduations.

Relationships and employment. Both the blissful beginnings and uncomfortable endings.

After the fact, we may construct plausible narratives linking those events together. Chains of cause and effect. Charting our course. Using them as milestones measuring progress along life’s journey.

Occasionally there really were goals, and a coherent plan to achieve them. Rare, but it does happen.

The Personal Finance community is big on goal setting.

Budgets.

Magic numbers.

New years resolutions.

Targeted savings rates.

Defined by the individual, for the individual. The “personal” part of Personal Finance.

Something the Personal Finance community is less keen on is comparison. Fearing that the “thief of joy” may find them wanting or instil feelings of inadequacy.

Which is interesting, because when we stop and think about it, few of our goals are unique or original.

Ideas originate from somewhere. Possibilities we read about. Experiences we have vicariously observed or heard of.

From our peer groups.

Communities of convenience or shared interest.

The media, in all its forms.

Examples may include the desire to own a nice home. Full of nice things. In a nice neighbourhood. Even the very definition of what constitutes “nice” itself.

Dreaming of financial independence. Freeing time investment decisions from monetary concerns.

Exploring a bucket list full of trophy postcard destinations and holiday brochure lifestyle choices.

Pursuing exceptionalism. A chart-topping album, Nobel prize, novel, Olympic medal, or an Oscar.

Had we not harvested ideas, by comparing our own lives with how others choose to live theirs, then the chances are high we would never have known any of those hopes and dreams were possibilities.

The art of the possible

Nearly a decade ago, Jonathan Kwok penned a column for The Straits Times asking how realistic it was for someone living in Singapore to accumulate a net worth of SGD$100,000 (GBP£52,000) by the age of 30.

Not a trust fund baby, lottery winner, nor inheritance beneficiary. Not even a high flying investment banker, just a mere mortal university graduate who was roughly five years into their chosen career.

Kwok started with the median graduate salary.

Factored in annual pay rises. Performance bonuses. Asset allocation decisions.

Assumed no long-tailed financial commitments. Dependents. Student loans. Mortgages.

His findings were both fascinating and controversial.

Over such a short time horizon, asset allocation had little impact on the outcome. It was saving rates that made all the difference, demonstrating that it isn’t what you earn, but what you keep which determines financial success.

A consistent savings rate of 20% saw the mere mortal graduate accumulate SGD$50,000 by age 30.

Increase that saving rate to 50%, and a net worth of SGD$100,000 by 30 was readily achievable.

Kwok was quick to observe such an existence would be challenging in a high cost of living location like Singapore, requiring surviving on just SGD$32 per day. Feasible for someone still living at home with their parents. More difficult for someone paying their own way.

Kwok’s article gave rise to a “$100,000 challenge”, where young Singaporeans attempted to turn that magic number into a financial reality. The goal wasn’t bragging rights or the celebration of an arbitrary round number, but rather to establish a solid foundation that in time could provide financial security and the luxury of choice.

A successful challenger could simply invest their accumulated nest egg at a 5% real return, sit back, and coast towards becoming a millionaire by around age 75 without ever saving another dollar. Few would select this option, but having that outcome as a viable choice by age 30 is a mighty powerful thing!

Comparatively speaking

When I first heard about the $100,000 challenge, I must admit I wasn’t very impressed.

Not because focusing on savings rates or preparing for the future were bad ideas. Quite the opposite.

Saving SGD$100,000 was a great achievement, an example most would be well served to emulate.

No, I was concerned that the challenge wasn’t ambitious enough. The target represented a fantastic first milestone on a financial journey. A beginning, not the end.

Back in 2013, the median net worth in Singapore was roughly SGD$116,000. Even those successful challengers would still find themselves in the bottom half of the wealth distribution.

Meanwhile, median annual household income from work was SGD$94,464. This meant a successful challenger had managed to squirrel away only slightly more than one year’s median earnings by the time they turned 30.

Both shortcomings would usually be addressed by the passage of time.

As challengers age, their careers advance. Salaries increase. Investments compound and grow.

Net worth climbing towards further milestones, supporting both financial goals and lifestyle choices.

The challenge highlighted several key reasons to save hard during our twenties.

First, we are more adaptable, forgiving, and tolerant than we will be at any future time in our lives. After spending years living like a student, subsisting on a diet of beer, ramen, and peanut butter sandwiches, we don’t know any different.

Continuing to live like a student, albeit one now earning an income and maintaining a high savings rate, is much easier than attempting to walk back accumulated lifestyle inflation. Frugality is like jogging, allegedly good for us, yet you rarely see a jogger looking happy while they are running!

Second, the magic of compounding returns is in the number of compounding periods. A portfolio left to compound for 50 years will likely be a great deal larger than one compounding for just five years. The earlier you start, the greater the number of compounding periods your money will experience.

Third, at that age most of us are responsibility free. Few of those momentous “life happens” events, which alter our course or derail our plans, have happened yet. Children. Dependent elderly parents. Illness. Marriage. Mortgage payments. Instead, we can afford to enjoy ourselves, while enjoying the freedom to be single-minded without being selfish. A transient and fleeting state of being that seldom lasts for long.

This raises some interesting questions.

Is there value in an individual striving to hit an arbitrary round number by an arbitrary birthday?

Would success be more likely if the challenger enjoyed the support of like-minded peers pursuing the same goal?

And finally, what level of savings rate is sustainable over the long term?

The answers to these questions are in large part determined by our earnings capacity.

At the shallow end of the earnings spectrum, savings are considered a luxury item. There exists an absolute floor below which our cost of living cannot be reduced without adversely impacting our health and wellbeing.

Beyond that point, savings become a possibility. Then an increasingly good idea.

The more we earn, the greater both the amounts and proportions we can potentially save. Highlighting that the most lucrative financial investment we are ever likely to make is maximising the marketable value of our time by investing in ourselves.

Allowing us to work smarter, not just harder or longer.

Buying control of time. Creating options. Granting the luxury of choice.

How much and how fast we can grow our savings is driven by an all-important fourth question: how much is enough?

Enough cash flow. To live comfortably, not compromised. Able to enjoy the journey, not pine for the destination.

Enough liquidity. As a 30-year-old, going all-in on inaccessible home equity and age-restricted pensions might be optimal from a tax perspective, but neither option would be much help buying the groceries or coping with an emergency.

Enough security. Becoming a millionaire at 75 sounds pretty good. Becoming a millionaire by 40 sounds even better. The game doesn’t end when the milestones of $100,000 or the challenger’s 30th birthday are reached. Instead, the prize provides the foundation for a financially secure future.

Enough self-awareness. To know when the game has been won, and it is time to stop playing.

Where those lines are drawn can and should vary from person to person.

Determined according to their individual perspectives, priorities, risk tolerances, and values.

Lost in translation

At the time of writing, the equivalent purchasing power of the original $100,000 challenge was GBP£61,000.

However, a simple foreign exchange conversion is misleading.

Purchasing the median net worth in the United Kingdom requires nearly GBP£250,000, roughly 4x the challenge amount.

Yet, a median annual household income is just GBP£29,900, less than half the target amount at the conclusion of the challenge.

Why the disparity? Two countries with two very different Personal Finance environments.

A factor worth remembering the next time you find yourself basing your financial approach on assumptions or methods researched and written about a different market. Common examples include expected market returns, sustainable withdrawal rate calculations, and key aspects of retirement planning such as social security or healthcare costs.

I found myself wondering what number a comparable challenge in the United Kingdom might involve?

Unlike Singapore, England does not currently have compulsory military service. This means graduates would have had two additional years to earn, save, and further their chosen careers.

Another key difference between the two locales is housing. In Singapore, roughly 72% of the population own homes provided via subsidised affordable public housing. By contrast, in my part of London, the waiting list for a public housing family home is both difficult to qualify for and over 10 years long! This suggests achieving an equivalent outcome requires a larger net worth in the UK.

To achieve that same ability to coast towards millionaire retiree status, the UK net worth by age 30 number would need to be considerably higher, at least GBP£100,000.

Is that realistic? According to the most recent HESA data, the median graduate starting salary was £24,217. The average annual wage growth over the last 20 years has been 2.85%.

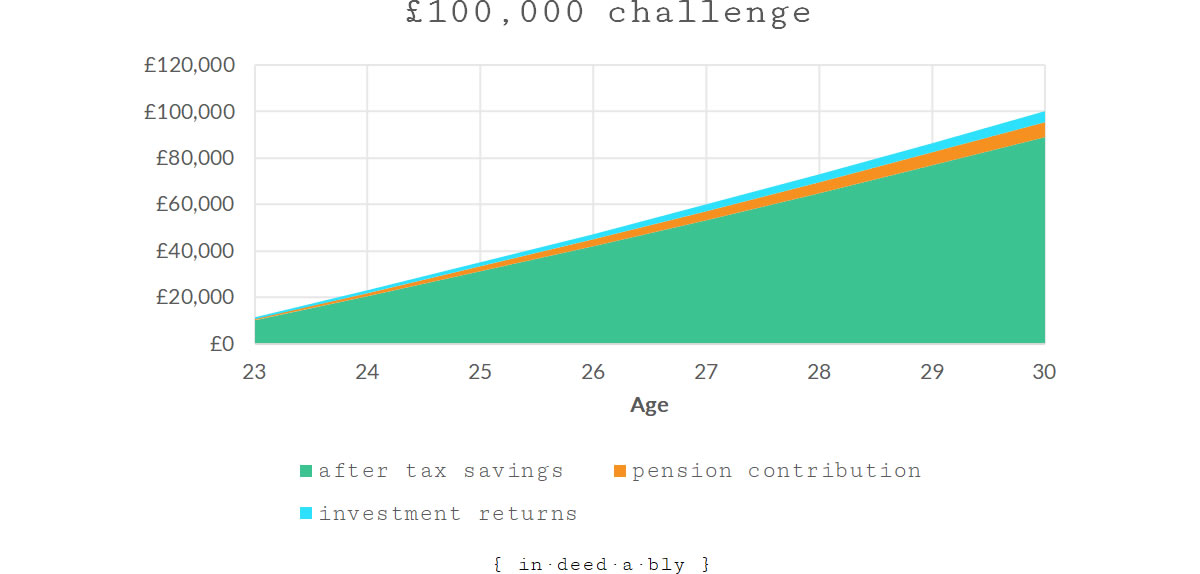

With a 50% savings rate, over an 8 year career, a median earning graduate could save roughly £89,000 from their after-tax income, plus another £6,500 in employer pension contributions. Investing those savings at a 5% average annual return would contribute roughly another £4,000, reaching the £100,000 milestone.

It is worth noting that most graduates would experience some form of career advancement or promotion during that period, so a £100,000 net worth by age 30 is certainly achievable, if not easy.

Milestone

Comfortable once more, I hiked along the path away from the ancient stone obelisk. Exploring the coast line and enjoying my journey.

It wasn’t until I reached the next milestone that I realised I had been resolutely marching in the wrong direction, further away from the train station that was my goal and marked my journey’s end!

Even with the best intentions in the world, our plans and goals will rarely achieve themselves. Setting sensible milestones play a key part in monitoring our progress and keeping us on track.

Ill-discipline, lack of preparation, or poor execution may conspire to sabotage our ability to succeed in much the same way that sharp pebble in my boot and my laughable sense of direction attempted to do that day.

I eventually reached the station, where I had to wait another hour after missing my train. A real life inconvenience caused by missing an arbitrary deadline. Better late than never!

The links below share the experiences of some folks who successfully pursued acquiring $100,000 by around age 30:

References

- Bank of England (2021), ‘Inflation calculator‘

- Budget Babe (2016), ‘Hitting $100,000 In Savings by Age 26‘

- Credit Suisse (2013), ‘Global Wealth Report 2013‘

- Gov.uk (2021), ‘Workplace pensions‘

- Higher Education Statistics Agency (2021), ‘Graduates’ salaries‘

- Housing and Development Board (2021), ‘Public Housing – A Singapore Icon‘

- Kwok, J. (2013), ‘Is it possible to have $100k by 30?’, The Straits Times

- ListenToTaxMan (2021), ‘UK Tax Calculator 2021/2022‘

- Miss FitFI (2020), ‘Saving $100k by 25 (What I Did – #4 is the Most Important)‘

- My 15 Hour Work Week (2015), ‘How We Saved $250,000 By Age 28‘

- Office of National Statistics (2019), ‘Total wealth in Great Britain: April 2016 to March 2018‘

- Office of National Statistics (2021), ‘Average household income, UK: financial year 2020‘

- OFX (2013), ‘Historical Exchange Rates‘

- Phneah, J. (2018), ‘How you can save your first $100,000 before 30?‘

- Ruiming, H. (2019), ‘The most important things I had to do to save $100,000* before I turned 30 in Singapore’, The Woke Salaryman

- Statistics Singapore (2018), ‘Key Household Income Trends, 2018‘

- The Simple Sum (2020), ‘How This Power Couple Saved $730,000 in 10 Years‘

- Trading Economics (2021), ‘United Kingdom Weekly Earnings Growth‘

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (2021), ‘Compound Interest Calculator’, Investor.gov

John Smith 7 July 2021

As always, I enjoy your excellent post.

Allow me a joke, about missing arbitrary deadlines: by the age of 30, I “acquired” a lady wife (profit center) and a 5 years old baby (cost center), plus no savings. Is this equivalent to 100K GBP? 🙂 No? shame on me! Then maybe “enough self-awareness” can compensate for other 500K? No again? Then I am hopeless. I should go back in time and then read your post. But I think I will make the same choices again as I did, because I felt so good.

{in·deed·a·bly} 7 July 2021 — Post author

Thanks John Smith.

That’s the thing about milestones and destinations, they are personal. Focussing fully on one aspect of life at the expense of all others is likely to end in tears. Going all in on family might leave you poorer, but going all in on money would undoubtedly leave you lonely.

The thing I took from the original $100,000 challenge was using our 20s productively. Most of us had no clue what we want to be when we grew up (many of us still don’t know!), so we drifted aimlessly and drank and travelled and had lots of fun. Richer in life experience for that, even if we were constantly broke.

Yet looking back on it now, I remember few of those gigs or city breaks or drunken backyard barbecues surrounded by dozens of happy strangers that I regularly enjoyed. I don’t really miss them, any more than I do the time wasting meetings and doomed projects I was often slaving away on at client sites.

With the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, I could have been a lot better organised with my finances during my 20s. Not changing all that much how I spent my time, but rather being more disciplined in actually investing savings and being more diligent in the property deal research I was often doing for fun but rarely acted upon.

That said, having never experienced a savings rate anywhere near 50% of my income, I had become a self-made millionaire by the time I was 30. Living frugally and conscientiously climbing the career ladder at a megacorp weren’t the path I chose, rather I opted for a lifestyle running my own business and doing property deals on the side.

What this story illustrates is what is financially possible for a median graduate, without using much imagination or lateral thinking. My own journey suggests we are capable of achieving a great deal more, but the lived experience of many will reveal most reach the age of 30 with a great deal less. None of those outcomes is right or wrong, better or worse than any others, providing we own the outcomes of our choices.

David Andrews 7 July 2021

Goals and targets are helpful but try not to let them take over your life. I’m told that some people have their lives mapped out with the milestones of home ownership and starting a family by certain ages.

Life simply doesn’t work like that. My net worth at 30 was rather lower than the targets in the article but I don’t think I was bothered. Truth be told, at 30 I was bimbling around without much direction. At 48 I continue to bimble around with possibly even less direction but my net worth is 7 figures.

A combination of being born at the right time and securing decently paid (mostly) continuous employment helped a lot.

What also helped was continuing to live below my earnings and eventually realising that conspicuous consumption rarely brings fulfilment.

If my family had provided a little more financial education my net worth could have been higher sooner with little adjustment to my lifestyle. I’ll be ensuring my son (presently 7) gets a decent financial education but also remembers to spend some whilst also saving / investing some.

Having enough cashflow and security means that once again I can take unpaid leave over the summer holidays and not worry too much about the impact.

{in·deed·a·bly} 7 July 2021 — Post author

Thanks David.

The thing about compounding is the magic takes time. Your example here of having little at 30 and lots at 48, while following a broadly consistent approach in between, is a great illustration of that in action.

I’d take broke and happy over comfortable yet miserable any day. But I would much prefer comfortable AND happy over either of those options, even if it would take a little longer to achieve.

Figuring out what we want can be challenging (and a moving target), but once we put in the work to do so, the planning and execution makes achieving those goals more than just a fluke of a possibility. Setting milestones helps us stay on the path. I’m told setting deadlines can help motivate some people, for mine they just create unnecessary stress.

I agree with your conspicuous consumption point. Nobody cares. Truth is, nobody is watching.

Bsdb3 9 July 2021

Another interesting post, I believe most saving/investing sucess is down to a lifestyle choice rather than targets. The targets are interesting and great to achieve but it’s the day to day buying and earning choices that make all the difference. Life events will occur, targets might come fast or slow, so it’s the habits that are really important.

In my teens and 20s I was quite profligate with cash – silly things like buying lunch and coffee at the office; if there was something I wanted I would simply get it. In my late 20s I realised I was accumulating lots of ‘crap’, had saved very little money and needed to do something. In 10 years I’ve doubled my net worth 3 times now, and hopefully will complete the 4th within a few years. If I had my time again I would do things differently and like David said earlier I’ll try to pass that learning on to my kids.

I understand in-lock down the saving rates have risen for some quite considerably. It’ll be interesting to see if that habit has formed. The other issue might be if everyone starts saving significant % of their earnings, and how well the economy might perform.

{in·deed·a·bly} 9 July 2021 — Post author

Thanks Bsdb3. You’re exactly right about the habits.

I wonder whether that spendy stage is something we all need to pass through at some point, in order to develop that value filter which we use to weigh up the effort required to earn the amount a potential purchase will cost us.

In this way we don’t sweat the small stuff, lattes and avocado toast, but do pause before signing up to a leased sports car or time share holiday apartment we’ll never use.

Well done on the triple double, best of luck on the next repetition. The numbers get bigger each time, but as compounding investment returns start to contribute ever more, the later ones feel easier than the early editions did. At least they did for me, your mileage may vary!

Q-FI 26 July 2021

I had never heard of that Singapore challenge. Very interesting. I especially find it fascinating when like you did, you start comparing cultures and currencies and play at equalization. Hard to do but can be a fun exercise.

Most people can somewhat grasp cashflow, liquidity and security. It’s the self awareness, in my opinion, that is so key. Which the majority of people tend to struggle with once the ambiguity of life comes into play.

{in·deed·a·bly} 27 July 2021 — Post author

Wise words, Q-FI. Thanks for reading.