Bob frantically rummaged through his wardrobe for his formal gown. It was gone!

Some thieving bastard had “borrowed” it. Again!

Normally such an event would be a minor inconvenience. Today it was a disaster.

The formal dinner in the Great Hall was about to start, and they turn away late arrivals.

Normally he would just skip it, and grab some food elsewhere.

Today that presented two technical problems.

First, Bob was flat broke.

Second, Bob was starving.

He could go to the dinner without the gown, but doing so was frowned upon. He would cop some snide condescension and casual racism about being an uncultured colonial. Business as usual.

Worse still, it incurred a penalty.

Students violating the Great Hall’s arcane and pretentious etiquette rules were required to stand in front of the assembled diners and consume a tankard of ale in less than 25 seconds.

Drinking beer was no great hardship.

In fact beer was the staple item in Bob’s diet.

It also the reason for Bob’s current dire financial circumstances!

The problem was the offender had to pay for the beer, and pay double if they failed to consume the roughly two and a half pints within the prescribed time limit.

And Bob had no money.

Unless…

Several weeks before, during a particularly heavy night’s drinking, Bob had been regaled with some of the ancient (and frankly ridiculous) Oxford traditions that are blindly followed to this day.

One such tradition was the accused student had the right to challenge their penalty. When such a challenge was issued, both of the student and the “sconcemaster” issuing the infraction, had to skol a tankard of ale.

The penalty was waived if the student could drink it fastest.

Deciding he had nothing to lose, Bob dashed out of his room and headed for dinner in the Great Hall.

The rest is history.

As expected Bob was penalised, then successfully downed the tankard of ale faster than the “sconcemaster”.

In fact, faster than anyone in recorded history. Talk about motivated!

That night in University College’s Great Hall, Bob broke the beer drinking world record.

There are few problems beer cannot solve

Many years later Bob became Prime Minister of Australia. He credits the beer drinking world record as being the single largest contributing factor to his popular appeal. It is certainly what he is best remembered for!

A close second however, was Bob’s infamous promise:

“by 1990 no Australian child will be living in poverty”

It was a noble goal, but as any junior consultant quickly learns, you should never commit to a deadline that you aren’t absolutely certain you can comfortably meet.

A decade later British Prime Minister Tony Blair dug himself into a similar hole with the promise:

“And whilst there is one child still in poverty in Britain today, one pensioner in poverty, one person denied their chance in life, there is one Prime Minister … will have no rest… until they too are free.”

Poverty

Poverty is a bit like pornography, in that it is hard to define but easy to recognise. For example:

- Children attending primary school without winter coats.

- Homeless people.

- Migrants subsisting locally in order to send the bulk of their income home to support their families.

- Pensioners wearing overcoats in their lounge rooms because they can’t afford to put the heating on.

The poverty line

The United Nations defines the poverty line as being “the amount of money necessary to meet basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter”.

This approach uses an absolute value: what it costs to survive. That is certainly definitive!

The World Bank set the international absolute poverty line at USD$1.90 per person in 2011, which at the time of writing was the equivalent of USD$2.18.

For the United Kingdom that equates to roughly £630 per person, per year.

Once those essential needs have been met, the topic of poverty become incredibly subjective.

Some folks may argue surviving is enough. Worrying about issues such as quality of life and social exclusion are a luxury, reserved for those who already have enough to eat and a safe warm place to sleep.

Others argue survivorship alone is not enough, everyone should have the opportunity to thrive.

Until recently, the “poverty line” was officially defined in the United Kingdom as households earning less than 60% of the median equivalised household disposable income.

In 2017 that United Kingdom median household disposable income figure was £27,300, which in turn meant poverty line would have been set at £16,380 under the old definition.

That £16,380 is much higher than the World Bank and United Nations absolute poverty levels!

Does that mean the United Kingdom has a posher class of extremely poor people? Probably not.

Or maybe, as a society, Britain (used to) generously set the bar for “enough” at a higher level than much of the world?

Or perhaps a more likely explanation is that survival in the United Kingdom is an expensive business!

Poverty is measured by income…

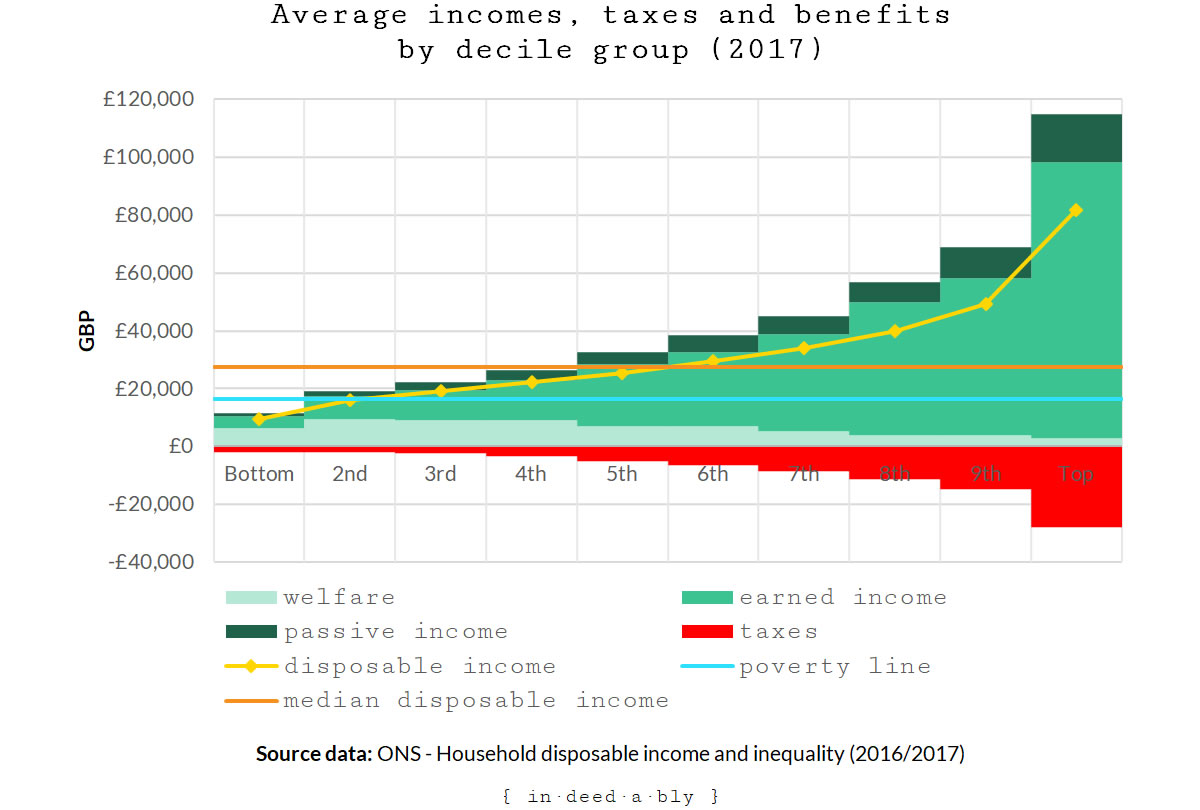

The chart below illustrates the average high-level composition of household income and taxes by decile group. The yellow line plots the average household disposable income within each decile group.

The vast majority of the population landed above the old poverty line. This is by design, but is good news nonetheless.

A disheartening thing the figures reveal is nearly two-thirds of households receive more income from welfare payments than investments.

… but expenditure determines their adequacy

One criticism of using income figures as a poverty measure is that it only tells part of the story.

Income levels are interesting, but without also factoring the cost of living, we cannot assess their adequacy.

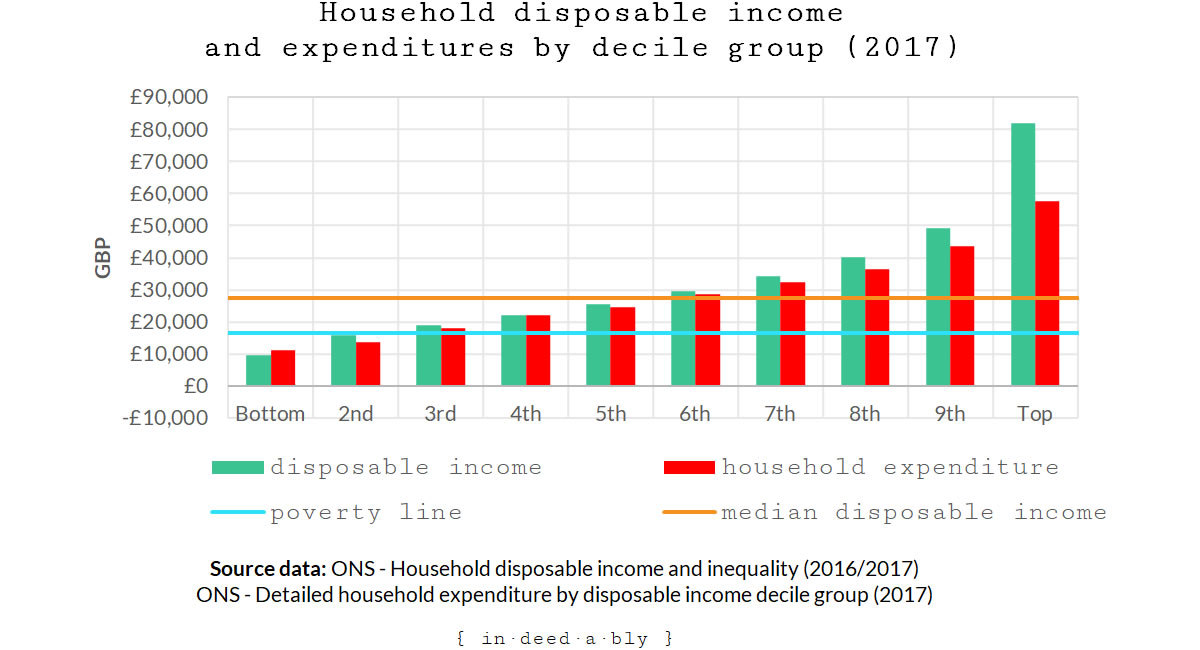

The next chart displays average household disposable income against average household expenditures, split into those same decile groups.

Alarmingly, the bottom decile group spend more than they earn, and earn less than the poverty line. Witness the poverty cycle in action.

If the poverty line represents the bare minimum that a household needs to earn to survive, then the bottom two decile groups are certainly doing it hard.

The earnings of the fourth decile group may exceed the poverty line, but their average expenditure slightly exceeds their earnings. That is not a recipe for financial success!

Savings rates determine financial wellbeing

Savings rates are a key metric for financial wellbeing. Somebody smarter than me once said “it isn’t what you make, it is what you keep that makes you wealthy”.

Different people have different methods of calculating savings rates, but fundamentally they all seek to measure the proportion of earnings that are retained.

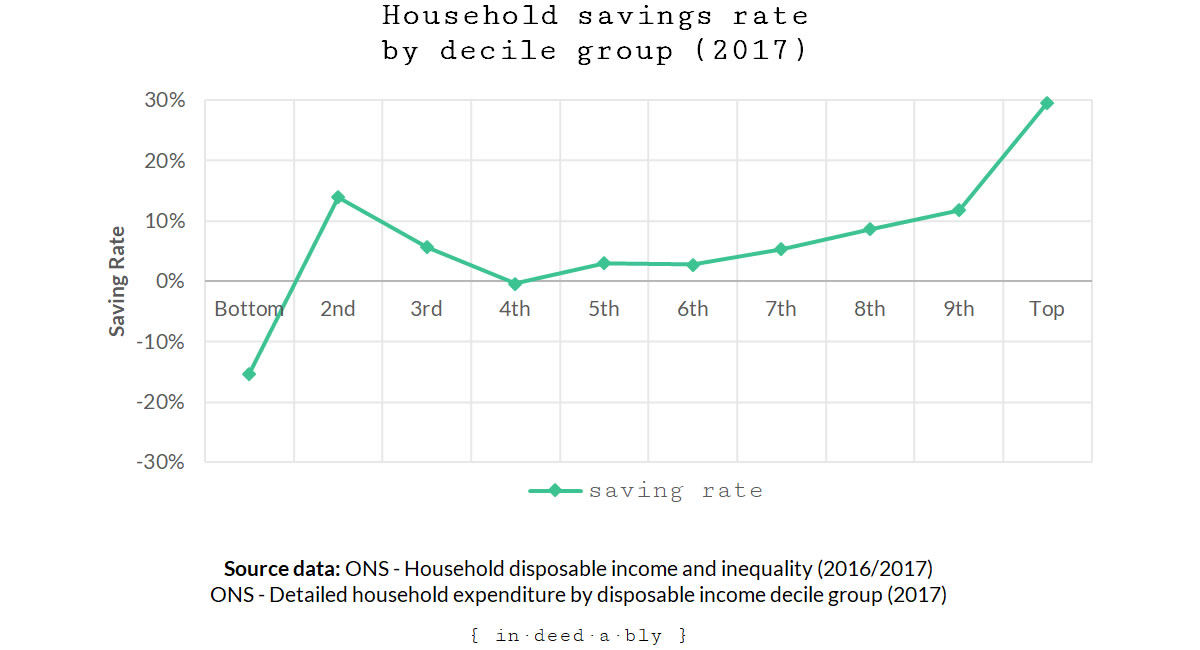

Using the average household disposable income and average household expenditures data, the next chart plots the savings rates for each decile group.

The second decile group is an interesting one. As expected their average earned income figures are roughly halfway between those of the bottom and third decile groups.

However on average the second decile group receives significantly more welfare than either the bottom or third decile groups, specifically in the form of housing benefits; working and child tax credits; and employment and support allowances.

As noted the fourth decile group on average doesn’t save anything.

The expenditure data shows this group spends almost as much as the fifth decile group on housing, transport, holidays, and fun. The expenditure levels in these categories are far higher than those of the third decile group. The fourth decile group is a case study in “keeping up with the Joneses”.

The savings rates of the fifth, sixth and seventh decile groups are negligible. These were Theresa May’s “just about managing” households: spending almost all that they earn, and only a sneeze away from financial oblivion.

The ninth decile group has an average saving rate of 12%. In the wise words of Young FI Guy:

“Financial Planners don’t agree on much, but they all agree that a saving rate of 10-15% just isn’t enough”.

Only the top decile has a decent average savings rate, in the region of 30%.

Is Financial Independence possible for everyone?

I believe the financial approach required to achieve Financial Independence should be applied by everyone.

The fundamental principles introduce good financial discipline. They create a margin of safety to help households weather the inevitable financial shocks that occur throughout life.

- Earn more than you spend.

- Maintain a contingency fund to smooth out the ride.

- Recognise that deferred spending is not the same as saving.

- Strike a balance between enjoying today and providing for tomorrow that works for you.

- Establish the real value to you of potential purchases. Do you need it? If not, will it make you happy? If not… then why buy it?

- Invest the difference between your earning and spending.

- Remember that money is a merely tool, not a purpose nor a goal.

Once these basic behaviours are established, go invest your time in something that adds value to your life.

Financial Independence is NOT possible for everyone

Unfortunately there are a lot of myths and misinformation that get perpetuated under the banner of Financial Independence.

One such myth is that achieving Financial Independence is a possibility for everyone.

It isn’t.

Looking at the disposable income and expenditure statistics above that clearly is not the case.

The average household disposable income earned by the bottom three decile groups is near or below the poverty line. This means that approximately one-third of all households are struggling for their very survival.

While the disposable incomes of the fourth and fifth decile groups do exceed the poverty line, they are still materially less than the median household disposable income level. They are surviving, but for the most part are struggling to make ends meet.

With good financial discipline, the fourth and fifth decile groups should be able to save a small portion of their incomes. However to claim the meagre savings rate possible at this income level make Financial Independence a realistic possibility is disingenuous.

By definition these bottom five decile groups contain half the population.

It is dishonest to pretend that these folks are going to be able to save their way to financial independence.

Invest in yourself

Everyone does have the option of investing in themselves.

Of increasing the marketable value of their time.

Of improving their earnings prospects as a result.

Many of those at the lower end of the earnings spectrum are already paddling very fast just to keep their heads above water. While “invest in yourself” sounds simple in practice it is far from easy.

That is not an excuse to not do it however!

Achieving a goal, such as reaching Financial Independence, often requires making trade-offs and sacrifices.

Making sacrifices when there is a realistic chance of achieving the desired outcome is potentially a worthwhile endeavour.

The day beer loving Bob Hawke became Prime Minister he went teetotal, remaining “on the wagon” until he left office eight years later. He viewed giving up alcohol as a necessary sacrifice for achieving his goal, leading his nation to the best of his abilities.

However where a goal is an unrealistic pipe dream, the making of those same sacrifices would be a foolhardy waste of time and energy.

There is a reason many of the Financial Independence writers come from high earning while collar professional backgrounds.

Financial Independence does first require the earning of a reasonable income. Until that prerequisite is met, the promise of Financial Independence is a dangerously oversold dream.

You don’t have to make big money, but it certainly helps!

References

- Hawke, B. (1994), ‘The Hawke memoirs‘

- Office of National Statistics (2018), ‘Detailed household expenditure by disposable income decile group, UK: Table 3.1‘

- Office of National Statistics (2018), ‘Household disposable income and inequality‘

Caveman 25 November 2018

Another great post indeedably.

Could I test your premise that FI isn’t for everyone? I agree FIRE may not be for everyone, but those are two different things. My understanding (which may be wrong) is that if you manage to work and earn c. £162 a week ( which is I think around 20-21 hours a week at minimum wage) you pay National Insurance. If you pay NI for 35 years you get the full state pension of around £164 a week i.e. you maintain that lifestyle.

At that point you are FI under most definitions right?

Is that really not a realistic aspiration for most people (leaving aside those that have medical reasons why they can’t work)?

My contention would be that if you know that you will be FI at 66, 67, 68 etc then you can still look to follow your 7 rules above to see what you can do to improve on that situation. That could be working more hours, trying to earn more per hour etc.

I know that I’m being pedantic but I believe everyone can have a better tomorrow. It’s the incurable optimist in me!

{in·deed·a·bly} 25 November 2018 — Post author

Challenge away Caveman.

My definition of Financial Independence is the point at which unearned/passive income reliably and sustainably covers a person’s lifestyle costs. (Whether a withdrawal rate approach is sustainable is debatable, but for the sake of argument I’ll include it in the passive income bucket.)

By that definition a single person living on the dole and receiving housing benefits could be considered Financially Independent already, providing they are content to live within the financial constraints of that welfare income.

I’m not picking on unemployed folks here, rather demonstrating that modest expectations result in the bar being lowered for Financial Independence.

In theory, the more a person earns, the less assistance they receive in the form of welfare benefits. To achieve Financial Independence, every pound they require to support their desired lifestyle that is today funded via selling time for money, would need to replaced either by investment income or welfare.

If you’re a worker at the lower end of the earnings spectrum, but desire a higher standard of living than can be financed by welfare alone, then it will be very challenging indeed to save and invest the required amount necessary to generate that unearned/passive income.

Ultimately the options for achieving Financial Independence are straight forward, a combination of: earn more, consume less, or take longer.

The problem with the “take longer” option is for many folks who earn below median incomes, it would realistically take more time than they could reasonably hope to live.

Caveman 26 November 2018

Yes I think that the key pillar of my argument is that of consuming less – and being content with consuming less. If you are surviving on welfare then I very much agree that the scope to save and invest is significantly more limited.

There are a lot of people in the UK who survive on the state pension alone. They are theoretically FI but I wouldn’t imagine that they all feel that way.

{in·deed·a·bly} 27 November 2018 — Post author

Or investing in yourself to earn more. It is a lifestyle choice.

The first chart shows a material portion of income for 70% of the population comes from welfare. Even above the median household disable income people still rely on tax credits to fund things like childcare.

My turn to challenge your premise: is Financial Independence a feeling? I think it is a measure, like the odometer in your car. It may be fleetingly exciting to watch it tick over an arbitrary milestone, but ultimately it won’t make you feel any different.

What Financial Independence does is give you the luxury of choice. Control over how you invest your time, without the financial imperative making those decisions for you.

The exercising that control by choosing to do more of what makes you happy (or less of what makes you unhappy… not the same thing!) is what feels different, not the arbitrary number itself.

There aren’t too many things people want to do after achieving Financial Independence, that they couldn’t already be doing in some form.

It is a question of priorities.

ermine 30 November 2018

Bravo on deconstructing the false dream analytically. The situation is worse than I had thought – observation showed the poor were never goign to become FI – if you are renting then even the SP is probably not enough. But how high the problem drifts up the income scale surprises me.

> There aren’t too many things people want to do after achieving Financial Independence, that they couldn’t already be doing in some form.

Hmm, not working for The Man was the aim of FI for me, and that’s pretty much all of nothing 😉

{in·deed·a·bly} 30 November 2018 — Post author

Thanks for the kind words ermine.

I concede, if your only goal was to stop working for “The Man” then it would be a tad challenging to achieve while continuing to do so!

Decisionsdecisions 26 November 2018

Applying those principles will undoubtedly put you in a better position regardless of your income level. The potential to see the FI goal as pointless however must increase the lower your income level is as the path and returns will likely appear or be unattainable as you highlight.

The reduction in DB pension schemes being offered by employees does however mean that more people at most income levels need to be thinking about and aware of how to build a DC pension pot with the aim of making life easier in retirement.

Currently the option of a 25% tax free lump sum 10 years before UK state retirement age offers a good opportunity to provide valuable funding towards early retirement. Increased awareness of this tax break and certainty from the government that the lump sum will be retained could make people more open to saving for the future at most income levels, as the tax break would make some of the heavy saving lifting required easier. The lure of jam today though is a tough one to overcome particularly when the future of the UK seems so uncertain.

A more historical normalised interest rate of say 5%, not impacted by central bank intervention such as QE might also encourage people to save more as the capital required to generate a material income would reduce significantly to perhaps a more attainable level. Any thoughts?

{in·deed·a·bly} 26 November 2018 — Post author

You make a good point Decisionsdecisions.

Providing for their retirement is something everyone should do, but much like flossing most folks fail to do nearly enough.

For widespread adoption it would need to be mandatory, done to people rather than with them. It would also need to be linked to the tax system to ensure the required contributions were made etc.

The Australian model would be a reasonable place to start, though even with a ~20 year head start on mandatory pension contributions, the contribution rate remains too low to viably fund retirements for more than half of the earnings spectrum.

That is the real issue: if you don’t earn much then you can’t save and invest much.

Even with all the compounding magic in the world, and fair market winds at your back, if you’re earning peanuts then a self funded retirement (never mind Financial Independence) is unfortunately always going to remain out of reach.

Decisionsdecisions 26 November 2018

I might just take Bob’s lead then and start drinking heavily…… what’s the point in trying! ?

{in·deed·a·bly} 27 November 2018 — Post author

I think the take away is that unless you try to help yourself, nothing will change.

Nobody will do it for you.

weenie 27 November 2018

Interesting question from @Caveman about whether people who survive solely on state pensions would consider themselves FI – I too suspect the answer is no. I can’t imagine that they have a lot of choices with such low income and like you, @indeedably, my definition of FI is that it should give you choices.

I’m nowhere near FI yet I think about the choices I’m already able to make every month – after my bills have been paid, I choose where to invest/save my spare cash. Those on the poverty line don’t even have that choice so already, I’m at an advantage, although by your graph, I apparently fall into one of the ‘just about managing’ decile groups!

Also, as well as having the time, it takes a certain mindset to want to earn extra money, be that a second job or side hustle and then another mindset to commit that money to savings/investments instead of just spending it to make your life more comfortable/less miserable now.

Us folks in the FIRE community have the luxury of opting to do side hustles (of our choosing) because we don’t need the money to get us above just surviving. Those on the poverty line need the cash to better their lives and will unlikely be thinking about their futures, so even with side hustles/second jobs, FIRE is unlikely to be possible for most.

And yes, I agree. Everyone must try to help themselves – no one (not the government) is going to save you…

{in·deed·a·bly} 27 November 2018 — Post author

Thanks for the considered and well articulated comment weenie.

To a large extent you are already winning once you have the luxury of being able to choose whether to save or spend. As the poverty line suggests, survival has a minimum cost requirement associated with it.

Also having the luxury of time available to invest in further education, second jobs, or making some money on the side. Some folks, migrants who send most of their money home for example, feel the need to graft away all their time just to make ends meet.

The hard part for many people is recognising that a short term sacrifice may be required to achieve a longer term improvement, retraining in a more marketable skill for example.

This requires time, money, and will power. For many of those stuck at the bottom end of the earnings spectrum, they lack both the time and the money required to be able to afford the retraining. It can be a vicious cycle.

thefirestartercouk 27 November 2018

Can’t disagree with your main assertions in this post and I said as much in the FI Podcast I did with Ms ZiYou.

However there are huge variations in personal circumstances for any given person at a given income level, so just because you are only earning say 20k/year does not necessarily mean FI is out of reach. It almost definitely is if you are living anywhere near London, but elsewhere I’m sure it could be possible.

Another point is that this data set of household incomes gives you no information about stage of life. I would imagine that a fair portion of the lower income households are simply starting out in life and so have lower incomes, and they will have time to increase that as they get older and have more experience. I started out on 18K/year so I would have roughly in the third decile taking into account inflation (if I lived alone of course). I’m not saying everyone can do this but it must account for quite a few as I say.

One other elephant in the room that I find no one really talks about is that, in my opinion at least, you have to have a certain level of intelligence to be able to absorb these FI ideas, implement them, and be OK with going against the herd. Just like your median income example, by definition not everyone can have above average intelligence. I’m not saying you have to be super brainy by any stretch but I would imagine the bottom say 25% of the country in intelligence almost have no chance of getting on board with any of this. Maybe I am being a bit harsh, not sure, but it’s just my gut feeling from the anecdotal evidence I’ve seen over the years.

Obviously I agree that the basic tenets such as try not to spend more than you earn, SHOULD be applicable to everyone (99% of people), but I also have great sympathy for people who are really on the poverty line, and with no means to escape, and therefore have no chance of FI apart from maybe Caveman’s pretty grim definition of it above.

Cheers!

{in·deed·a·bly} 27 November 2018 — Post author

Thanks for reading TFS.

The figures are “equivalised” (which I’m pretty sure isn’t a real word, but they use it on the ONS website!), meaning they get adjusted to account for the varying size of the households being surveyed.

I think you are partly right, that some of the lower end of the spectrum households are just starting out. There would also be a lot of older folks surviving on the state pension. A significant third group would be in there too: the disabled, low income earners, and the unemployed who receive significant welfare assistance to top up their incomes in order to survive.

I disagree with you on the intelligence point.

It has been my experience that the human race’s propensity for stupidity is boundless. That holds just as true for the folks who believe reality television is not scripted, as it does for the highly educated academics and C-suite executives who often carry on like moody toddlers with short attention spans.

The principles of Financial Independence are simple. Putting them into action requires self discipline and control, rather than superior intelligence. Like exercising and eating healthy, achieving Financial Independence is simple, but not easy.

thefirestartercouk 28 November 2018

Yea good point about the pensioners as well!

Re: Equivalised… equivalised to what, 2 working adults per household? Does that mean if it’s a one person household (or flat) they would simply double that persons income and say that was their “household income”? What about a household with 2 working age adults but one of them chooses not to or just doesn’t work? What about children in the household, do they account in this equivalised formula?

As usual there is a lot behind the statistics that are not at all obvious from first glance here.

(I’m not expecting you to answer any of my questions above btw, I’ll go check out the report now)

“I disagree with you on the intelligence point.” – Not actually sure we are disagreeing here? I wasn’t saying intelligent people would find FI stuff a walk in the park, was simply saying that less intelligent people would find it harder both from an income tends to scale with intelligence factor, and a self discipline and control factor which as you rightly point out is a huge factor in reaching FI.

I’m fairly certain that that sort of thing scales with intelligence as well, as a general rule. Also, there are different kinds of intelligence (e.g. IQ, street smarts or common sense, emotional intelligence, and so on) and I would say that control and discipline IS a kind of intelligence in itself, probably in the “emotional intelligence” bucket.

But yea obviously there are plenty of people who are booksmart but not introspective enough or emotionally intelligent if you will, to follow through with FI type ideas.

Cheers 🙂

{in·deed·a·bly} 28 November 2018 — Post author

According to Eurostat, “equivalised” is figured out as follows: