“My house must be worth over one million dollars!” crowed my elderly mother.

She had recently joined her long time neighbours in watching the auction of a property located down her street. My mother was quick to point out that the house had been smaller than her own. Not as well laid out. Very dated inside. The outgoing neighbour hadn’t updated the décor since the 1970s, when chocolate brown, burnt orange, and lime green had been the height of fashion.

Much to their delight, a bidding war had erupted. The final bid was enough to launch the seller into the ranks of the “two comma club”!

One of the bidders was an amateur landlord. Planning to convert the suburban home into a group house for up to a dozen fly-in commuters, who flock to the city to kick start their professional careers.

Their competition was a young family. Heavily backed by the “Bank of Mum and Dad“, spending an advance on their inheritance to house their growing tribe. The self-contained “granny flat” behind the garage provided the grandparents with a modicum of hope that there was an alternative to being consigned to the aged care exit lounge, once they could no longer look after themselves unaided.

The beauty of a property auction is the contract certainty it provides. No chains. No changing minds. Buyers hoping to score a bargain. Sellers wishing for overeager bidders to inflate the sale price. Once the hammer falls, the deal is done. Both parties committed.

A couple of decades ago my parents had moved into their “forever home”. The worst house on a street with a nice view. Located in a shabby suburb that, while never fashionable, was by then well past its prime.

At that time, most of the houses on the street contained owner-occupiers at a similar stage in their lives. Careers topped out. Children about to leave the nest. Mortgages nearly conquered. The prospect of retirement evolving from an abstract concept to being visible on the horizon.

In the years that followed, my mother provided a running commentary on the comings and goings on her street.

Early on, it was random “life happens” events that had thinned the herd.

Death. Disablement. Divorce. Illness. Job transfers. Redundancy.

Later, it was retirement age residents seeking a higher quality of lifestyle. “Treechange” or “seachange” were popular choices. Relocating to small beachside villages or rural towns, once they no longer needed to worry about sabotaging their children’s educations or finding paid work locally.

Others chose to move closer to their children and grandchildren. Dishearteningly often, those same children and grandchildren soon moved away yet again.

The composition of the neighbourhood gradually changed.

Owners left.

Tenants moved in.

Initially families. Later group houses.

Neighbourhood schools merged. Then closed their doors, as demographic changes collided with ever-constrained budgets. Resources were reallocated towards younger suburbs containing more children.

Public transport services were steadily reduced as demand dwindled. Now a single meandering bus route runs once per hour. Passengers arm themselves with a packed lunch and a good book before boarding, on a good day the ride takes more than an hour to reach the nearest transport hub. A ten minute journey if taken by car.

Commercial regional medical centres replaced local doctor and dental practices. Consolidating non-emergency medical services into hubs where attention is sold in 5-minute intervals with no continuity of care.

The neighbourhood shopping centre contained more empty shopfronts than occupied stores. The new breed of locals preferring to dine, shop, and socialise in more fashionable surroundings. Gone were the days of the neighbourhood being full of stay at home parents, university students, and retirees.

Car parking had become a problem. Garbage bins up and down the street overflowed. Far more residents now lived on her street than the local infrastructure could comfortably cope with.

This most recent house sale meant there were now only a few of her original neighbours remaining. Her address may have remained the same, but the neighbourhood had markedly changed.

Yet here is the thing. The city’s population had grown by more than 40% since she moved in.

To accommodate all those new arrivals, the city had rapidly expanded.

Urban sprawl on the affordable outskirts. Gentrification and urban infill closer to the centre of town.

Without moving an inch, my mother’s house had steadily become better located, as the local citizen’s perception of what represented a “good” commute gradually evolved.

As those perceptions changed, so too did the market value for the housing blocks on her street.

Which brings us to this week, when those market prices exceeded an arbitrary round number.

Suddenly that worst house, on the street with a nice view in a tired unfashionable suburb, had her feeling like she had joined the ranks of those living on Kensington Palace Gardens, Nob Hill, or The Peak.

Providing bragging rights and a warm fuzzy feeling for those long term neighbours.

I was thrilled for my mother. It was fantastic to hear her happy with her neighbourhood, rather than focussing on the changes that had adversely impacted liveability, the polar opposite of progress.

Popular myths

Later that day it occurred to me that my mother’s feeling of wealth and prosperity due to rising property prices was largely a carefully crafted illusion.

On paper, her net worth had increased.

Yet accessing this newfound wealth would require her to sell up or extract equity via a loan. Neither of which was a desirable outcome.

The value of all the surrounding houses would have appreciated at much the same rate. This meant gains made from selling one property were cancelled out by the higher asking price of the next one.

Those seeking to climb the property ladder require even more funds. Better location or larger block size incur a larger price tag. One that rising property values are likely to similarly have inflated.

Owner-occupiers only win the game when they downsize. Selling up their appreciating property, then buying a smaller or less desirably located property. The remaining sale proceeds could then be used to finance lifestyle choices or accomplishing bucket list items.

The other cohort of winners from rising property prices are inheritance beneficiaries. Being gifted a potentially tax-advantaged former principal place of residence, free from stamp duty taxes on the title transfer. The higher the property prices, the larger the windfall gain.

According to Zoopla, back in the late 1980s, the average British owner-occupier moved home once every 8.63 years. By 2017, that average rate of homeownership turnover had slowed to once every 23 years.

This meant that for many, their “starter home” acquired as first home buyers became their “forever home” by default. I wondered why this might be?

Had people suddenly become more accepting and content? If the level societal discord that has been exposed by movements such as Black Lives Matter, Brexit, and Scottish Independence is anything to go by, the answer is probably not.

Perhaps the clichéd growing family’s desire for more space had been solved by simply not having as many kids?

Fertility rates have fallen by 10% during that period, from 1.82 live births per woman in 1988 to 1.65 last year. That would account for some, but certainly not all of the less frequent house moves.

My next thought was transaction costs. The top rate of stamp duty has risen from 1% to 12% during this period (15% for those who already own another property). Those rates can be misleading however, as in practice stamp duty is applied via tiered pricing bands.

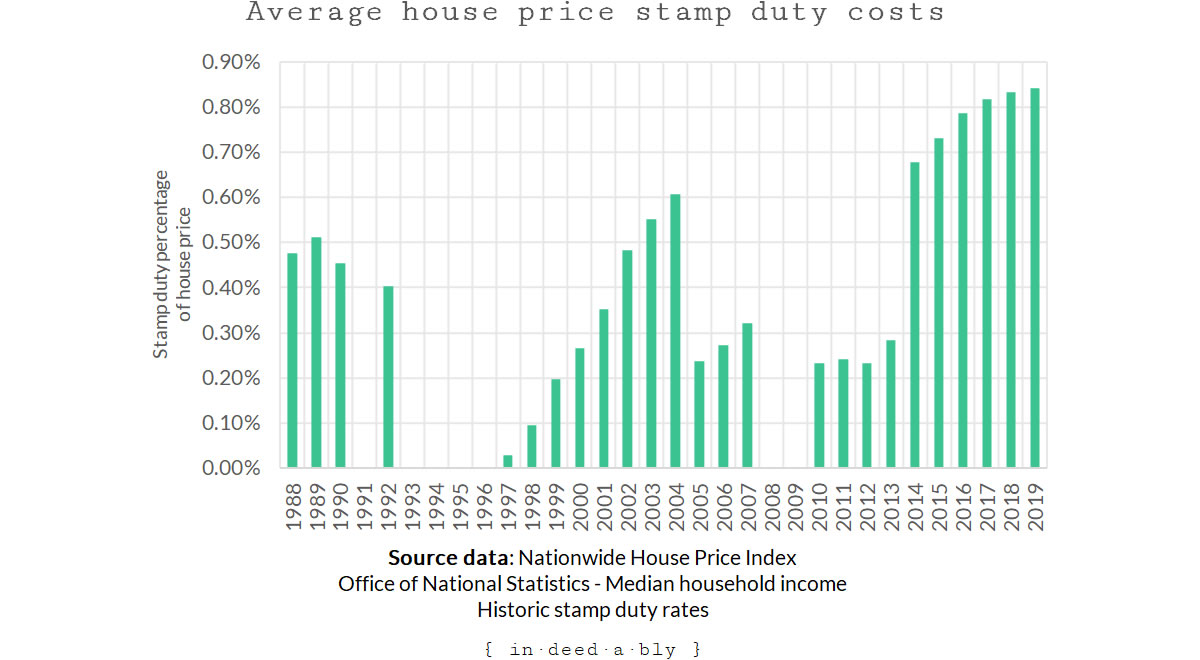

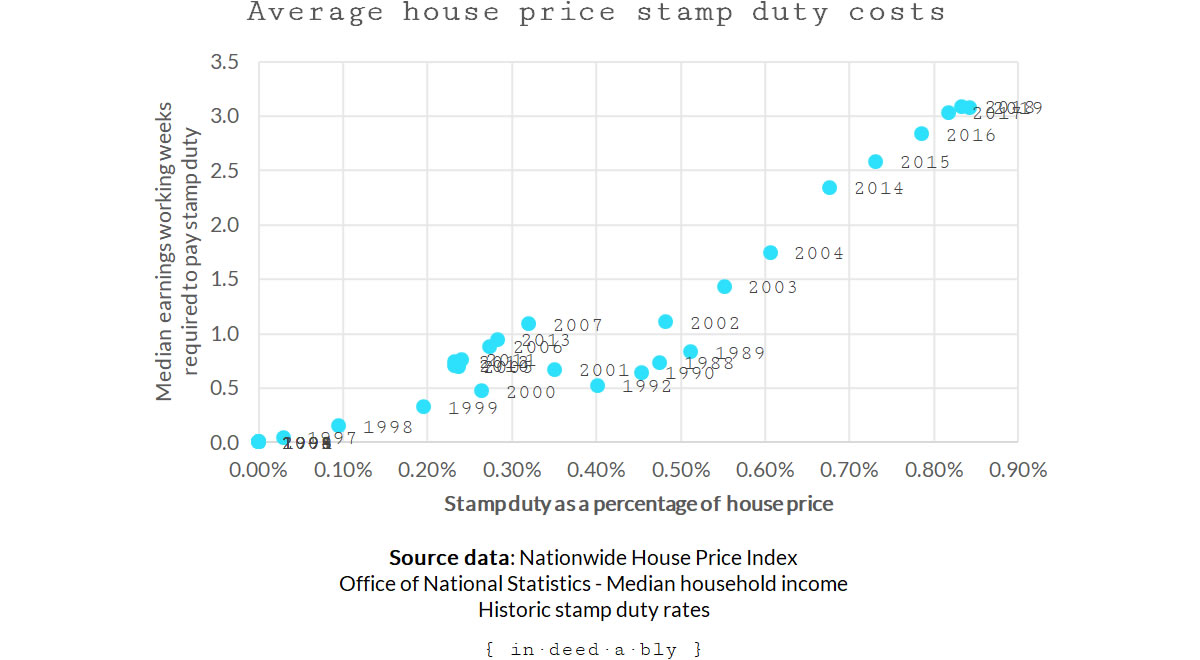

I looked up the historical stamp duty bands and rates. Then I applied them to the Nationwide average house price dataset to see how transaction costs had changed over time. The rate has bounced around on the whims of vote buying politicians, ranging from nothing to almost 1% of the house price.

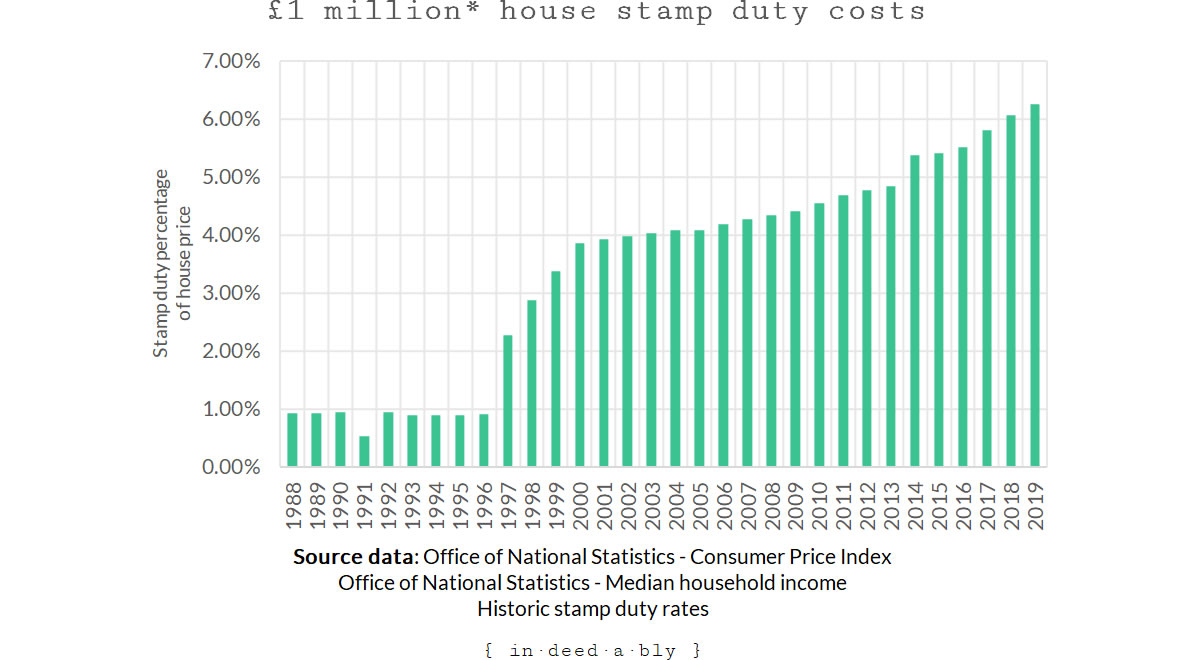

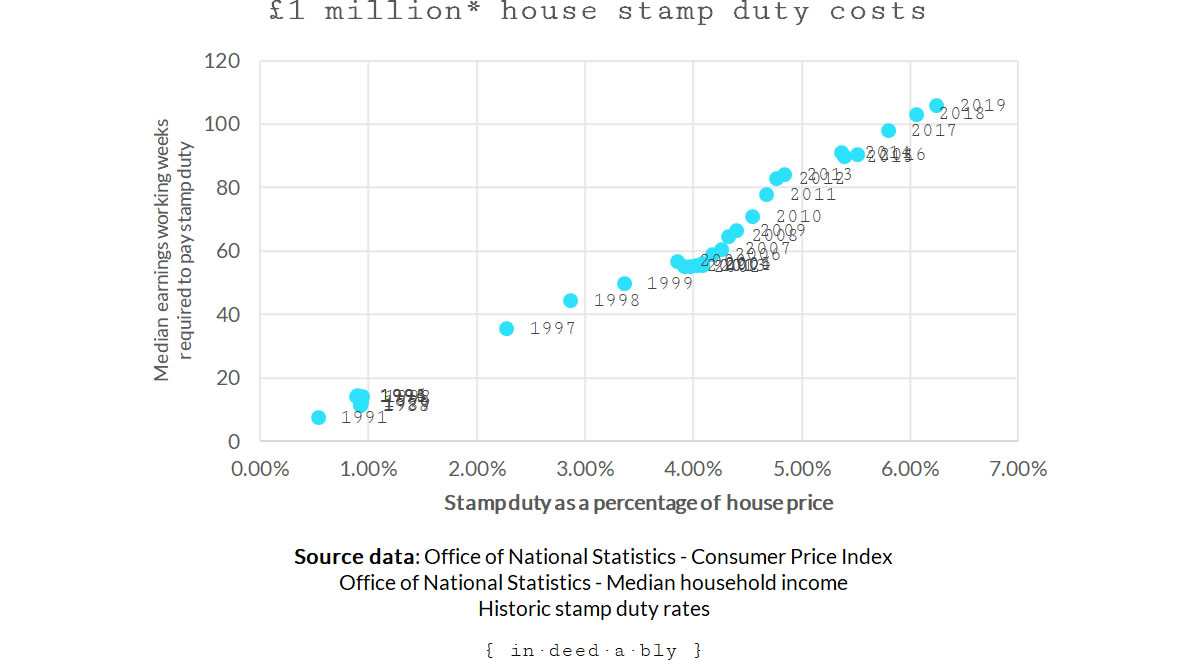

That was interesting, but that “average” house price doesn’t buy much more than a car parking space in much of expensive London. I wondered how my mother’s property millionaire status would have played out here?

Starting with a notional £1,000,000 property in today’s money, I determined what the inflation-adjusted value would have been for each year back to 1988. Once again I applied the historical stamp duty bands and rates to those values. This time the stamp duty cost nearly 6% of the house price!

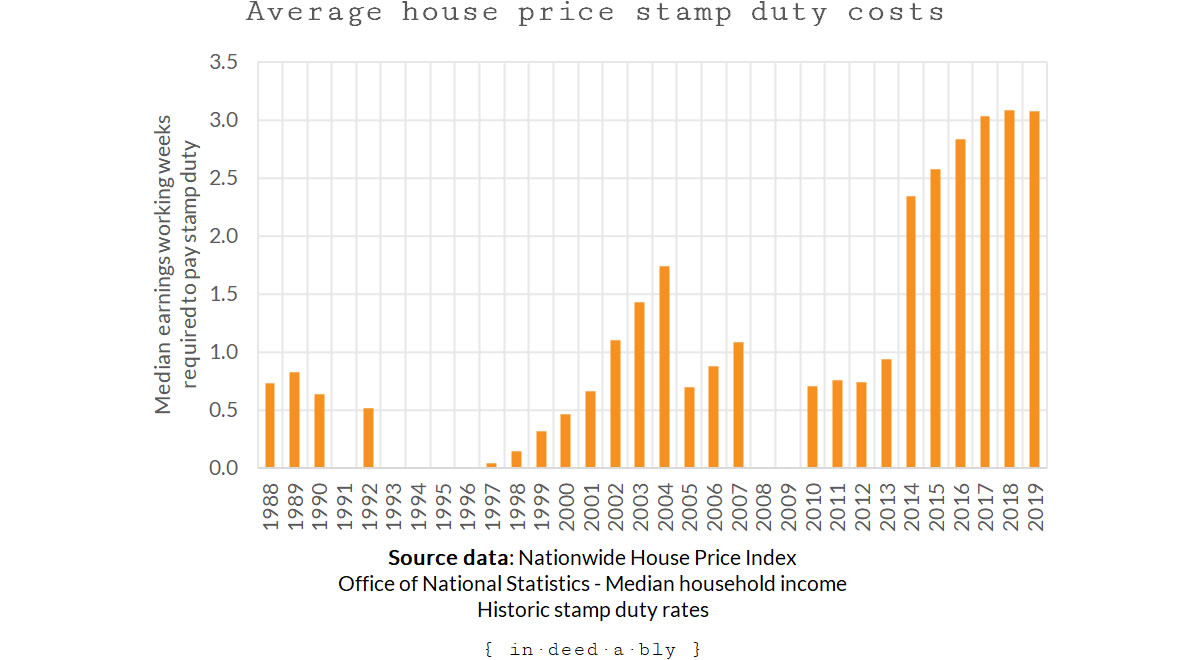

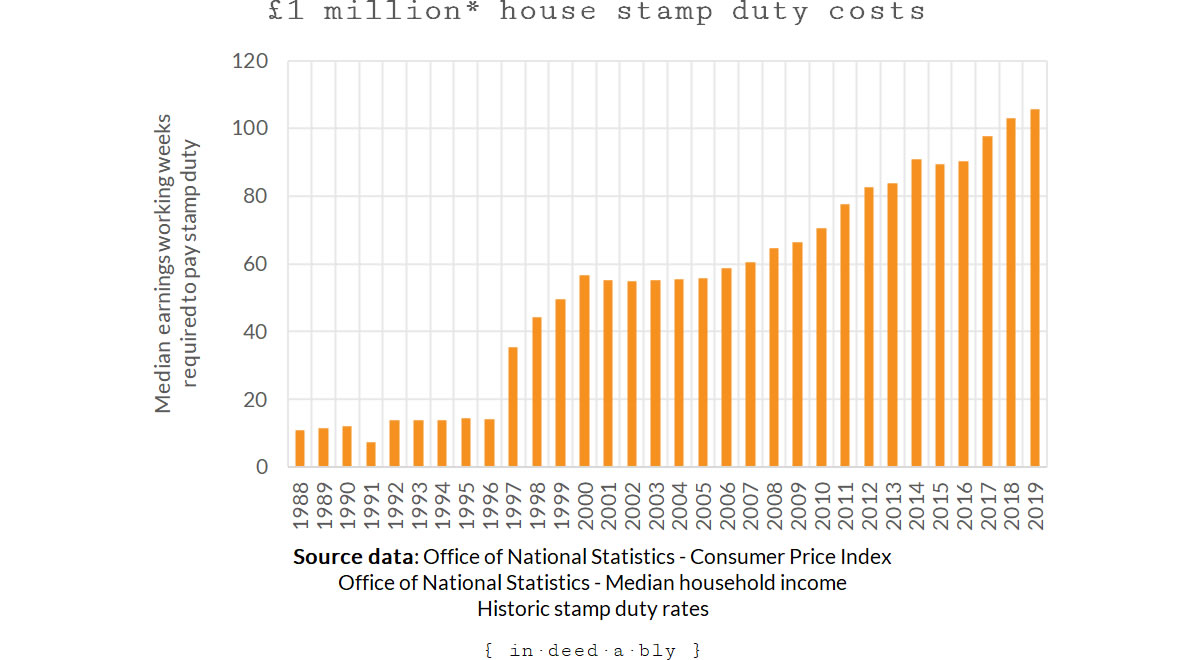

Next, I got curious about how much those amounts equated to in terms of time investment? I looked up the historical median earnings dataset and calculated how many working weeks were required at median earnings to cover the stamp duty costs of a property purchase.

For the average house price, it ranged from nothing to a little over three working weeks.

For the million pound house however, the median earner would need to work for more than two years just to pay the stamp duty taxes incurred on the purchase!

Pulling those two measures together, we can see that the transaction costs of purchasing a house have soared over the time period. First the average priced house.

Then the million pound house. When the amount of effort required to pay transaction costs can be measured in years, it raises some troubling questions about the financial viability of the owner-occupier lifestyle choice.

In reality, those wanting to purchase a million pound property are likely to be earning far more than the median household income. Even for those on higher incomes, the transaction costs associated with property purchases in the United Kingdom are non-trivial.

From a young age, we have been conditioned to unquestioningly accept certain popular myths about home ownership.

That homeownership is always superior to long term renting.

That the property market is a ladder. Implying we must climb successive rungs toward our the ultimate destination. Those Zoopla figures suggest that ladder has become a short one for many of us, little more than a single step in some cases.

That transaction costs should be tightly monitored and minimised when it comes to pensions and ISAs, but transaction costs are rarely mentioned when discussing the purchasing of a home.

I wonder whether we would be so accepting of that narrative, were the true cost of purchasing property expressed more clearly?

Buying that million-pound house would mean choosing to effectively pay 100% of your income for months or entire years in voluntary additional taxes.

Or, to express it another way, that the buyer would be voluntarily postponing their potential retirement date by up to several years just to earn enough to pay those transaction costs from their after-tax earnings.

Which brings to mind a mantra that we should all be conditioned to accept: adopt a “buy and hold” approach to minimise transaction costs incurred by churn.

Transaction costs

There will come a time, in the not too distant future, when the frailties of age make the downsizing decision for my mother.

Regardless of whether her guesstimate of her home’s value are realistic or aspirational, at least she will be free to enjoy all of the proceeds. The jurisdiction in which she resides has eliminated stamp duty, opting instead for a recurring value-based land tax which reduces friction for property buyers and creates a more predictable revenue stream for the government.

Sydney recently announced they were adopting a similar approach, making it the latest major city to abolish stamp duty.

We should do the same in the United Kingdom.

References

- Foxtons (2019), ‘Behind the doors of London’s £3 billion street‘

- Freebairn, J. (2020), ‘Axing stamp duty is a great idea, but NSW is going about it the wrong way’, The Conversation

- Nationwide (2020), ‘House Price Index‘

- Office of National Statistics (2020), ‘Average household income, UK: financial year ending 2020 (provisional)‘

- Office of National Statistics (2020), ‘Births in England and Wales: 2019‘

- Office of National Statistics (2020), ‘Consumer price inflation tables‘

- Stamp Duty Rates (2020), ‘History of Stamp Duty Taxes‘

- White, D. (2017), ‘How often do we move house in Britain?’, Zoopla

Steveark 27 November 2020

I can’t fathom how people can afford seven figure homes. I bought my home for $32K forty years ago and after doubling its size the four bedroom, four bathroom, $3,000 sq ft house on two acres wouldn’t even bring $200K if I sold it today, most likely. The idea of paying six or seven times as much for a smaller house is frightening to me. Especially since wages are not proportionately higher in the UK. That has to be a drag on the rest of the economy with so much of consumer buying power being diverted to rent or mortgage payments? At least your mom should be able to recoup a good deal. Its fascinating to see how other parts of the world operate. Great post!

{in·deed·a·bly} 27 November 2020 — Post author

Thanks Steveark. I think we’ve concluded previously that your part of the world is winning in the cost of living stakes. I suspect the figures would be similarly eye-watering for some of the more expensive parts of the US, San Francisco or New York for example.

That is the thing, most people can’t afford seven figure homes. The average price of a terraced house inside London’s zone 3 travel area (think 45-60 minute commute to the City) was just over £1,000,000 last year, yet the median household income was only £30,773. That puts the average terrace house at a multiple of 33x median earnings.

The purchase price is only the beginning when you think about it. People still do all that same extending, renovating, and decorating that you have done.

So a lot of people trade time for money, in pre-COVID times subjecting themselves to 3-4 hours commuting per working day.

My mother is far smarter than I am, the properties in her neighbourhood are 8x median earnings, which would place financial stress on most households. With the benefit of hindsight, she looks like a genius for buying decades ago, before the house prices got away from her. That said, I can distinctly remember my parents having some blazing rows about how expensive the property was back then, and wondering how they would ever manage to pay the mortgage and do the renovations they felt it needed.

Property only ever looks cheap in hindsight!

GentlemansFamilyFinances 28 November 2020

As overpriced as property is, I was saying the same thing 15 years ago.

It is rightly or wrongly seen as the royal road to wealth and prosperity and if a bank won’t lend you money or give you a ridiculously cheap loan that you don’t deserve it is a major affront.

My Mum is around 70 as are here siblings and some live near a big city and others in backwaters. The difference in house price growth and number of kids means you can end up with a sixth of f-all or a million pound inheritance. I get the sixth so I am understandably anti-inheritance.

The value of the houses doesn’t necessarily reflect the overall quality of the house or neighbourhood but more the proximity to well paid jobs.

For my own life I’ve chosen to live in a LCOL city in Scotland- losing out on house price gains over the next X years but having a higher quality of life and easy mortgage.

When I think of those in London without bomad or that didn’t buy 20 years ago I feel sincere pity.

{in·deed·a·bly} 28 November 2020 — Post author

You’re absolutely correct GFF, property price is mostly a factor of location: schools, jobs, healthcare, transport links, etc. Dubious decorating choices may mean it takes longer to find a buyer willing to pay the market price, but are is unlikely to materially shift the needle on the price itself.

The London property market is much like the US stock market, overpriced then, even more overpriced now! The greater fool theory has kept things rising while London remained an attractive destination for migrants and British property appeared a safe store of value to overseas investors. Whether that continues to hold true after Brexit will be interesting to watch.

You make a good point about low cost of living locales, as Steveark also did earlier. Migrating several times has taught me that it is possible to make a happy fulfilling life anywhere, and people are people wherever you find them. Opting for a locale with a high price is a lifestyle choice, and often an own goal from a financial perspective.

FI-FireFighter 28 November 2020

Another great post and you summed it up with;

However there is another danger to be aware of –

I bought my first property in 1991, it was on the market for £39,950, I naively thought I had got a bargain when they accepted my first offer of £34k. Everyone was saying get on the ‘Ladder before it’s too late!’

I had a 100% endowment mortgage (single income I was only 23), interest rates went up and up, tough times.

That property was in negative equity for 9 years before I could sell it without a loss.

That was the catalyst for me to start my financial education.

I had little knowledge and was poorly informed.

I was determined not to let that happen again.

Nearly 30 years later reflecting back it was probably the best decision I ever made as it set me on a different path.

Since then property has been my go to investment choice/path and it’s been a quite successful.

{in·deed·a·bly} 28 November 2020 — Post author

Thanks FI-FireFighter. That sounds like quite an adventure for a young bloke, I’m glad you managed to survive intact and wiser for the experience.

I too am a big fan of property as an asset class. Investors can create value, use leverage (without the risk of margin calls), and it encourages adopting a long term investment perspective that would benefit most of us.

That said, there is a trap for young players trying to get into the market with limited financial means. They are forced into looking at “cheap” properties, like those marketed at first home buyers. These are often cheap for a reason: rubbish location with limited opportunities. Unfortunately, those same properties will likely still be “cheap” when the investor subsequently wants to sell them, because they are still located in a rubbish location with limited opportunities.

Some investors are some combination of astute and lucky. Identifying locations that are about to see their fortunes greatly improved. Infrastructure investments, major new employers setting up shop nearby, etc.

Others are asleep and unlucky, being on the receiving end of those same changes. A new highway bypasses the town and kills off the passing trade, or the major local employer shuts up shop or moves away.

FI-FireFighter 28 November 2020

Totally agree and those traps change. If I was cynical I would suggest some of them evolve and are even targeted at the young and those with the least financial awareness I.e those most vulnerable and most in need of help, support and guidance.

The help to buy scheme is a good/bad example. Hidden costs that can rise at any time by any level (service fees), intentionally short leases, responsible for 100% of property repairs, trapped in properties they cannot sell on.

Now the Govt are planning reducing the min % required to buy a shared ownership property down 10%!

They will ‘sell’ it as helping more people start on the ‘Ladder’ I don’t see that as being very responsible.

I started out in Cornwall and have friends down there who have been stuck in shared ownership properties for years. It was a dream to start with but it’s a slog to break free from and not everyone can.

But for many their choices are limited.

The rent v buy debate again!

{in·deed·a·bly} 28 November 2020 — Post author

I don’t think calling things how they are is cynical. First home buyers and shared ownership scheme buyers are prey, those developer business models depend upon their ignorance and those popular myths to succeed.

That whole “rent v buy” debate is framed wrong. There is no reason you can’t do both, same as there is absolutely no reason why you have live only where you can afford to buy.

No Free Lunch 28 November 2020

Whilst transaction costs may have gone up, the overall cost to a buyer should not have changed whether these transaction costs stayed the same, were reduced or gone up. Because the property market is a just a zero sum game if you also include the taxpayer. What reducing stamp duty does is simply transfer wealth from the taxpayer to sellers of property. So your conclusion that stamp duty should be scrapped (perhaps in favour of a land tax spread over future years) in order to encourage more movement does not really make any sense. Yes you will get a short term spike in number of transactions as evidenced this year by the SDLT holiday (where only the net seller benefits), but all you have really done is brought forward sales/purchases that were going to happen anyway and at a cost to the taxpayer. The seller benefits from higher prices and the buyer is indifferent.

If you are trying to find reasons for the increase in length of time people stay in their home, I think you will have to look elsewhere. I think it is because housing is very expensive in the UK particularly London. When people move, they usually move to a better area and the absolute cost would only have risen, so people just don’t see the point in moving or literally can not afford the move. Older people don’t really downsize in later life as its a huge downgrade in life quality.

Sometimes I think people need to go back and read econ101!

{in·deed·a·bly} 28 November 2020 — Post author

Thanks for sharing your thoughts No Free Lunch.

Replacing stamp duty with a recurring land tax produces a one-off spike in market prices by the stamp duty amount, as buyers suddenly decide they can afford to pay a little bit more. The recent UK pandemic stamp duty “holiday” illustrated that, as did the experiences in other cities.

What the change accomplishes is to help free up property supply, by encouraging cash poor property owners to sell up. That sees those older people reluctant to downsize, inheritance beneficiaries, and low income earners in gentrifying neighbourhoods to make way for new owners who are better able to afford those higher ongoing holding costs. It also discourages landlords from operating marginal properties, as the holding costs increase but the market rents don’t, again freeing up supply. Scarcity is one of the factors that drives up property prices, this helps to address that issue.

You’re absolutely correct that high property prices are the main impediment to property purchases, either initially or when upsizing. The thing is that property always feels expensive at the time, it would have been a long time since any homeowner bought a home in London and thought to themselves “Wow, that was really cheap!“.

Your Econ101 comment is interesting, as in your comment you assume the property market is a closed economy with no alternative uses for capital. That suggests prospective buyers would never find alternative uses for their capital, such as spending it on furnishings or holidays and sports betting.

No Free Lunch 28 November 2020

I agree that the SDLT holiday encourages those who are cash/cash flow poor to sell up but this comes at an obvious cost to the taxpayer. Why does it have to cost the taxpayer, why can’t the seller take the “hit” (if you can even call it that after such rampant house price inflation) without the SDLT holiday if they were in such a poor situation? Furthermore, I suspect a lot of retirees would fall into this “cash flow poor” category, but don’t they have DB pensions and state pensions to support their cash flow problem? Why not just turn off that tap by reducing the state pension to really force them to sell up? Wouldn’t that be much more beneficial for the UK’s finances as the taxpayer gets the SDLT and reduces their state pension liability? The answer to that is that politics always rules over long term public finances and a healthy economy.

The problem with your argument is that you are not seeing the losers and just seeing the apparent winners. Taxpayer have lost out, the buyer is indifferent and the seller gains. What you are saying is lets encourage more HPI to encourage sellers to sell. But this comes at a cost. It sounds absolutely absurd.

I never said that the property market is a closed economy. Maybe I should have made myself clearer but by zero sum game I meant the game of changing taxes only (i.e. all else equal which is a reasonable assumption) should be a zero sum game between the buyer, the seller and the taxpayer. When you reduce SDLT, you create HPI all else being equal. Of course, just like any market, the property market is subject to all sorts of factors affecting both supply and demand which results in price increase and decreases.

No Free Lunch 28 November 2020

If you really agree that high house prices are to blame for lack of moving, why implement a SDLT holiday that will only increase house prices further? Completely crazy.

If you want to solve the problems that occur with high house prices, increase interest rates and limit low skilled immigration.

{in·deed·a·bly} 28 November 2020 — Post author

I think we’ve gone down a tangent here.

The current stamp duty holiday was a silly idea, a government subsidy to stimulate demand and keep rent-seeking estate agents and conveyancing solicitors afloat. You are correct that it provided a one-off windfall gain to sellers at the expense of buyers and taxpayers.

The switch from a one-off stamp duty paid only by a small number of property buyers each year to a recurring value based land taxed paid by all property owners every year can be tax revenue neutral. It subsequently provide the government with an easy means of raising revenues that is very difficult to avoid or evade, a wealth tax of sorts.

As for reducing access to social security to encourage sales, this actually a good idea. Means testing all assets (including owner occupied housing), then providing support only to those who are not in a position to support themselves. There is something wrong if a pensioner can be sitting on a valuable asset (my mother would be an example here), yet still able to claim an aged pension if they choose to.

At this point I think we agree to disagree. Thanks for the fascinating debate.

No Free Lunch 28 November 2020

How is it off tangent? You provided some nice looking analysis on transaction costs and came to the conclusion that stamp duty should be scrapped to encourage more transactions. I am merely providing a counter argument, one that disproves your case.

With a reoccurring land tax, again someone’s gonna benefit (the taxpayer) at the expense of somebody else (sellers and maybe buyers). I think it is a better idea in order get the housing market moving and the more punitive the tax the better up to a certain point. It may not be an upfront transaction cost, but it is certainly a cost that any prospective buyer and seller would need to consider. So much will depend on how punitive this tax would be. It may get too much that low earners won’t be able to afford it. Pensioners may still be able to afford it if state pensions remain generous. Politics will ultimately decide what happens in the end.

Q-FI 28 November 2020

You know, this is a topic that I think everyone at some point in their life, regardless of geography will be able to relate to or have an opinion on. Great post and I agree with you that the only way to unlock value is to downsize and not trade up. However, I think too many people treat their house like an asset, even though they wouldn’t be willing to ever downsize.

Real Estate is such a tricky subject because it is not only location dependent, but neighborhood dependent. Like you in London, I also live in a high cost of living City and am actually in the process of looking for a home. It has been a crazy process to say the least.

As Steveark mentions above, sure if you live in Arkansas and a 3,000 SF house sells for $200K then housing is easy. However, I live in Los Angeles and a 700 SF 2 bed, 1 bath house STARTS at $700K. A 3,000 SF house would most likely be north of $2M easily (not that I would ever need nor want that much space, a 1200 SF 3 bed, 2 bath suits me just fine). Even in the absolute boondocks you will not get a house for less than $500K. How you handle a housing market like this, (which I’m sure London is very similar), is a complicated and personal decision.

In my case, I’ve rented for a long time and wanted to build up my paper assets significantly so that those would be on auto pilot before I ever took the plunge into buying a home. However, the thing that’s happening now, at least in the LA market during COVID, is that there are such bidding wars, buyers are waiving their appraisal contingency. So what you’re seeing are cash buyers come in first, then people who waive the appraisal need to fork over cash for the downpayment as well as the significant gap between the purchase price and appraisal. Pretty wild, but these are the times we live in. For me, I’m not willing to waive the appraisal so it’s been a waiting game so far.

{in·deed·a·bly} 28 November 2020 — Post author

Thanks Q-FI. An owner-occupied house is definitely an asset, as it could be sold and converted into cash. I think most folks would accept that. A more contentious question is whether it should be considered an investment. The Kiyosaki fans would argue not, as it consumes cash without generating income.

It sounds like Los Angeles is a very frothy property market at the moment, with folks offering over the odds for properties they will have trouble obtaining finance to purchase. That is happening a lot in London at the moment also. Lenders here anticipate turbulent economic times after Brexit, and have consequently tightened their lending criteria. Most high loan to value mortgage products have been withdrawn from the market, appraised values are increasingly conservative, self-employed folks have trouble accessing finance, and so on.

The thing about owner-occupied property is that buyers often take the plunge for purely emotional reasons. It will be their home. Where they will raise their family. Their safe place to escape the world. Which means many buyers make decisions that are not financially rational, which in turn makes the buying experience trying for the rest of us, just as you are experiencing.

Good luck with your property adventures, I hope you manage to find a home that meets the needs of your desired lifestyle and your financial well-being.

Stonebridge Kestrel 30 November 2020

Well, this all sounds very familiar.

I’ve lived my three bedroomed London terraced house for nearly 20 years – it was the first home that my partner and I bought together when we we hit 30. I traded in a small new-build flat which I had bought in 1997; she was still renting.

As you observe, it’s a long time since anyone bought in London and thought “gosh, that was cheap”. We certainly didn’t. The price in 2001 was just over £200,000, and we borrowed around 160K on joint earnings of 50K. Paying the mortgage wasn’t a struggle, exactly, but it was a big part of our monthly budget. Now, like every other terraced house within striking distance of the City, it would sell for over a million.

[I think that London property was last an obvious bargain in the mid-90s. Even when I bought my flat in 1997, prices had been going up strongly for 18 months or so; hilariously, I was worried that I might be buying at the top – and I had to buy in a cheaper area than I had been renting in].

Obviously, we are much wealthier than we would have been if we hadn’t bought our house. My income is not that much higher in nominal terms than it was back then (it’s probably lower in real terms – I dare not work this out), but, somehow, I am a millionaire.

Despite this huge windfall, we are, as you suggest in your post, pretty much stuck here. We have been for many years. Even ignoring careers (both our jobs would be difficult to do elsewhere) and family (our children are settled in nearby schools), the basic financial challenge of moving within London is insurmountable.

If, for example, we bought a house with an extra bedroom in our local area, the transaction costs would be over £70,000, on top of the price difference between the two houses. The total “cost to change” would be not far short of 200K. And I’d rather put that sort of money towards retirement.

So, we’ll be here until our children leave school and we stop working, clocking up a quarter century plus in our “starter home”. Consider that in generational terms, and it’s hard not to conclude that the housing market, and the incentives enshrined within it, acts as a huge brake on the mobility and economic responsiveness of the workforce.

{in·deed·a·bly} 30 November 2020 — Post author

Thanks for sharing your experiences Stonebridge Kestrel.

Exactly.

Next overlay nationalistic politicians seeking reduced post-Brexit immigration, combined with a widespread adoption of remote working (often for many, always for some), and it raises some uncomfortable questions about what is going to be driving the demand for all those overpriced London properties over the next decade? Folks who bought recently may be in for an uncomfortable time of falling prices and negative equity, reminiscent of your fears about buying into a market peak back in the late 90s.

It will be interesting to watch how things play out.

David Andrews 30 November 2020

Many households in my area are choosing to build extensions to their properties. The cost of the improvements may add additional value and also avoid the need to pay moving costs and other new home purchase costs if they could even find a suitable property to move to.

New build properties in my vicinity are labelled as “executive” and demand a price much greater than they actually should. The gardens are tiny, with almost non existent storage space. When adding in the costs of selling, buying and moving it would make it a rather daft idea. One of the families we know were considering moving but have deiced their current property actually gives them more space.

I kept my first property when we bought our current family property. My first property is let out on a residential mortgage with consent to let. I’ll have to sell it, change the mortgage to BTL or clear the mortgage in the next 6 months – all those options are possible in my present circumstances but I’m struggling to come to a decision.

Maybe I should convert to BTL and extract some of the capital to buy another house in our local area. Perhaps, I’ll wait until after the end of the current buying / selling frenzy caused by the Stamp Duty holiday and see what happens to the local market.

{in·deed·a·bly} 30 November 2020 — Post author

Thanks David. That extend instead of move option is pretty common in my neighbourhood. Lots of loft extensions, and more than a few basements being dug out, particularly while the government has made it trivial to obtain/buy planning approvals that might normally be knocked back.

Sounds like you have a good range of options to choose from, just make sure to factor in the tax changes when you run your numbers. You can no longer offset borrowing costs against rental income, which has made many rental properties located in expensive markets cash flow negative. The changes are a double whammy, as it increases your taxable income (possibly causing bracket creep), while providing only a basic rate tax “credit“.

Good luck with your decision.

David Andrews 1 December 2020

Thanks for your response.

Juggling things round a bit and making maximum pension contributions just keeps me in the basic tax bracket in my current situation. Having almost used up my pension carryover doesn’t eave me much wiggle room.

I suspect there may be a number of landlords who are having to tell their tenants that renting a property is no longer economically viable and they will attempt to cash out.

Advising my manager that I will not be working overtime / out of hours shifts because it’s not worth it may be an “interesting” conversation.

Bob 1 December 2020

Well written as always. I envy your ability to explain to room temp IQ like myself.

There was an article in The Guardian this week about the return of the Sloane Ranger. A new generation of Sloanes having been priced out of Kings Road now live in streets like your mum’s.

The escape to the rural idyll worked well for me. But since January the demand led effect you ascribe to city dwellers has come to the remote fells and dales. Those tired estate agents boards that have haunted unsold houses for the last three years have suddenly grown bright “sale agreed” stickers.

The average house is 250 years old and a lot were not in great state or had unfavourable restrictions.

Having to chuckled at how little lockdown has affected the High Fells. What’s this? DEFRA has imposed lockdown on my geese!

{in·deed·a·bly} 1 December 2020 — Post author

Thanks Bob. You’re selling yourself short, but your turn of phrase made me chuckle!

A million years ago, I knew this estate agent in a little country town. In a good year he sold two, sometimes three, properties in total. An upgrade to the nearby highway made the town tenuously commutable to the nearby city. What followed played out exactly as you’ve described. “As fools rush in!” was the memorable line he used to describe the influx of newcomers willing to pay over the odds for what could be generously described as the “quaint” local properties which generally hadn’t chosen their previous owners very well.

Today, a couple of decades later, the town is all artisan sandwich makers and gourmet coffee shops. Those old shacks were occasionally restored, but more often pulled down (brown paper envelopes or friction fires overcoming planning/heritage restrictions) and replaced by enormous modern McMansions. The first generation of fools made out like bandits as amateur property developers, managing to find even bigger fools to pay even more money for the designer rural lifestyle image those new homes promised.

Dividend Power 2 December 2020

Wow! A lot in this article. But neighborhoods ebb and flow as towns and cities change. Most house values are flat for years and then take off for short for a few years only to level off again. It happens in cycles.

{in·deed·a·bly} 2 December 2020 — Post author

Thanks Dividend Power. That has been my experience also, fairly constant low growth, followed by short bursts of rapid growth when something structural changes like infrastructure or employment opportunity improvements.

Blissex 2 December 2020

«Most house values are flat for years and then take off for short for a few years only to level off again. It happens in cycles.»

Not in southern England in “good” tory areas: 7-10% valuation increased per year on average for the past 40 years, even with two crashes in those 40 years.

In southern England (and in south-west Australia) everything (politics, economy) is based on valuations increasing by an average 7-10%*forever*.

Blissex 2 December 2020

«For the million pound house however, the median earner would need to work for more than two years just to pay the stamp duty taxes incurred on the purchase!»

The way past past buyers see it is that they pay not a penny of transactions costs, the future buyer of their property to will pay all of that, plus a massive gain. When properties double in valuation every 7-10 years and rents double every 12-16 years, incumbents don’t need to worry about costs, tenants and the next buyers pay for everything.

That’s pretty much the entire basis of “thatcherism”, including “Tenants moved in. Initially families. Later group houses.”. “Neighbourhood schools merged.”, “a single meandering bus route runs once per hour.”, “Consolidating non-emergency medical services into hubs where attention is sold in 5-minute intervals with no continuity of care”, “more empty shopfronts than occupied store” aspects; all these things are irrelevant if prices double every 7-10 years. Look at your own mother: she is thrilled! Many people like her have framed even poster-sized portraits of Thatcher in their living rooms.

As “The Economist” put it several years ago, incumbent home owners, especially those who bought in the south in 1990s or earlier, have been awarded a massive collective lottery win by Thatcher and Blair, and little to nothing else matters in english politics.

{in·deed·a·bly} 2 December 2020 — Post author

Thanks Blissex.

Existing owners don’t care about the transaction costs associated with past purchases (except for the financial hangover they can cause!), but they certainly do care about them when they are looking to move house in the future.

The affordability challenges aren’t unique to Britain, nor to Thatcher however. Major cities in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and a whole bunch of other places all face similar issues (to varying degrees) where supply and demand imbalances have resulted in property prices growing at a far greater rate than local wages.

For many of us, financial realities demand we re-examine whether property ownership is a viable option. It is certainly granted favourable tax treatment, and applauded by society, but the fact is that for many it is now simply out of reach because they don’t earn enough to make the numbers work.

Blissex 3 December 2020

«they certainly do care about them when they are looking to move house in the future.»

Only if they are upsizing, and not many people can afford to upsize…

«The affordability challenges aren’t unique to Britain, nor to Thatcher however. Major cities in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and a whole bunch of other places»

Most of those places are “anglo-american” adopted thatcherite places even without the benefit of M Thatcher herself, as the notion that big fast property price increases make upper-middle and middle class people vote tory has spread.

In the 1970s one of the original neoliberal think tanks discovered a remarkable electoral fact: that people who owned property, cars and share pension accounts (in the USA add “owned guns”) tended to vote far more often for the right than people who rented, used public transport, had defined benefit pensions, *even at the same level of income/class/status*.

It turned out that of the three the factor that really mattered was property ownership, and the best way to incentivise property ownership is to ensure booming prices. Among many a sample quote from ConservativeHome.com:

“There were even prophetic council house sales by local Tories in the drive to create voters with a Conservative political mentality. As a Tory councillor in Leeds defiantly told Labour opponents in 1926, ‘it is a good thing for people to buy their own houses. They turn Tory directly. We shall go on making Tories and you will be wiped out.’ There is much of the Party history of the twentieth century in that remark.”

This plus the massive profits for their activists and sponsors (most of whom have property estates or financial interests) has made most anglo-american right-wing parties switch from being the parties of business to being the parties of property and finance rentierism, which is the enduring core of thatcherism.

«where supply and demand imbalances have resulted in property prices growing at a far greater rate than local wages.»

That is a common misunderstanding: there is an imbalance not in property supply and demand, but in job supply and demand. Property demand depends almost entirely on job availability, people move to some place to access jobs there. People from the rest of the UK, eastern Europe, and the third world have not been queueing to move to London and the Home Counties because of the ski slopes, or the sandy beaches, or the beautiful weather, but because of jobs.

And it has been thatcherite (whether Conservatives, LibDems, New Labour) policy to spend enormous amounts of public money to attract businesses and therefore jobs specifically to the Home Counties and London. This map of regional property price changes in recent times is highly meaningful.

If businesses and jobs were more evenly spread across the UK things would be very, very different.

{in·deed·a·bly} 3 December 2020 — Post author

Employment opportunities are certainly a major driver of population movement, both domestically and internationally. All those people need to live somewhere, driving up rents and house prices where the opportunities are (e.g. San Francisco in recent years) and seeing them wane where they are not (e.g. Detroit after the financial crisis).

Perhaps one positive thing to come from the pandemic may be a broader distribution of knowledge workers throughout the country, due to the wider adoption of remote working. At least until those jobs more offshore to even more remote workers who can afford to do them for lower wages!