There was a moment this week where I enjoyed the work I was doing. A feeling of conscious pleasure.

A vague concept rapidly evolving into a well executed idea.

Designed. Developed. Implemented.

Fit for purpose.

Working nicely.

A sense of achievement at a job well done.

Something tangible that I could point to and say “I did that”. It hadn’t existed when I started work that morning. Yet by day’s end, I had created something that proved remarkably useful. Saving time. Adding value.

The notable thing was that feeling. Long ago I used to experience it regularly. Now I honestly can’t remember the last time I finished a working day with that same tangible sense of accomplishment.

It has been a while.

Possibly years.

Yet here is the thing. Strictly speaking, I shouldn’t have been doing that activity at all. It was a job for someone decades my junior, who charges a day rate many hundreds of pounds lower than my own.

Over the years, my knowledge and experience has grown. As the scale of my professional “achievements” has increased, their ability to provide instant gratification has diminished. An inverse correlation.

An achievement is now measured in months rather than hours.

Delivered by multinational teams rather than by me alone.

Their measure of value containing ever more zeros.

Yet somewhere along the way, I lost the joy.

A sense of delight when a program compiles without error.

The warm fuzzy feeling of solving a genuinely challenging tricky problem.

That steady stream of bite-sized reinforcement that my efforts were making a difference.

My feeling of pleasure was a misdirection. Like a magician distracting the audience from what is important. A rugby player being thrown a dummy pass, their short term focusing in the wrong direction harms the team’s ability to win the long game.

It did feel good though!

Which lead to some uncomfortable questions. What other activities might I be undertaking, that seem like a good idea at the time, but are misdirected or counterproductive when it comes to playing the long game?

Small beer

Every week there are comments, debates, links, and stories about the best “high interest” savings account. An oxymoron in this low interest world.

The current flavour of the month appears to be the Marcus account, backed by the “too big to fail” Goldman Sachs. At the time of writing it offered an underwhelming annual equivalent rate of 1.05%.

Hardly a princely sum! Perhaps it represents the least worst choice?

After inflation, the real return on money held in a Marcus account at the time of writing was 0.15%.

To put that figure in perspective, consider an example. Sally Saver parks her £5,000 emergency fund in a Marcus account. After five long uneventful years, her account balance has the purchasing power of £5,037.64 in today’s money. Before tax.

Better than nothing, but hardly worth getting excited about.

Some people actively invest the time and effort required to churn these bank accounts.

Filling in forms.

Jumping through hoops.

Supplying the proof of identity and residence required by “know your customer” regulations.

All in pursuit of a tiny sliver more interest income.

Notionally a worthwhile endeavour. Seeking to optimise returns. Make their money work harder.

Chasing a “high” interest rate feels worthwhile because it provides the illusion of control. A tangible action the individual can take to improve their financial setup.

Yet, the return on investment for their time is negligible.

One-off inducements offered by the likes of FirstDirect to switch banks often exceed any interest earned over a comparable period. So too would a couple of small tax-free Premium Bond wins.

Chasing short term yield while ignoring total return is a trap. Those who do are playing the wrong game.

Blinkers on

Over the years I have gradually amassed a real estate portfolio.

I view each investment property as a stand-alone business.

Cashflow positive. Rental income more than covering the financing and operating costs associated with holding the property. Throwing off excess cash, to help finance my semi-retired lifestyle.

A good property is one located in an area that will thrive and outperform the prevailing market. Desirable locale. Good schools. Infrastructure investments improving access and facilities. Strong employment prospects. A scenic view would be nice, but it is worth remembering that you don’t own your view, so paying a premium for one that can potentially be built out is folly.

My preferred financing method is to wrap a property in an interest-only lending facility. Able to make capital repayments when convenient. Flexible enough that there are no minimum repayments. Never cross-securitised.

Rent flows into the loan account. Expenses flow out. A property manager takes care of the logistics. Over time the property pays itself off, without requiring any additional financial contributions from me.

A self-sustaining stand-alone business.

Set and forget.

Except every now and again it occurs to me that in operating a property in this manner, I am effectively borrowing money to pay every insurance premium, maintenance charge, and rates bill.

Paying interest on that borrowing.

Convenient. But expensive! Particularly if I had savings elsewhere that could cover that expenditure.

Viewing a segment of our overall portfolio as a ring-fenced silo is a trap. It leads to suboptimal asset allocation decisions. Seemingly correct within the confines of that blinkered lens, but illogical when examined in the context of the bigger picture.

Short horizons

When I was growing up, coverage of the financial markets on the nightly news consisted of a brief segment used to round out the half-hour bulletin.

Typically this took the form of a brief mention of the local market index, followed by some nonsensical statement like “investors fled to defensive stocks” that sought to fit a plausible sounding narrative to the random machinations of the global market.

The segment would end with a couple of infographics being flashed on screen displaying the daily movement in the major global market indices and currencies.

Back then investing was an insular inward-looking activity.

“Mum and Dad” retail investors had the choice of directly investing in domestic securities listed on the local stock exchange, or pouring their money into one of a small number of expensive actively managed funds who invested in the exotic-sounding “international” market.

But here is the thing. The local economy made up a small fraction gross world product. The proportion of global market capitalisation contributed by the local stock market was little more than rounding error.

To those living within, the local market was the whole investing world.

To those observing from the outside, the local market barely registered at all.

Roll forward to today, and local retail investors now have ready access to the major markets.

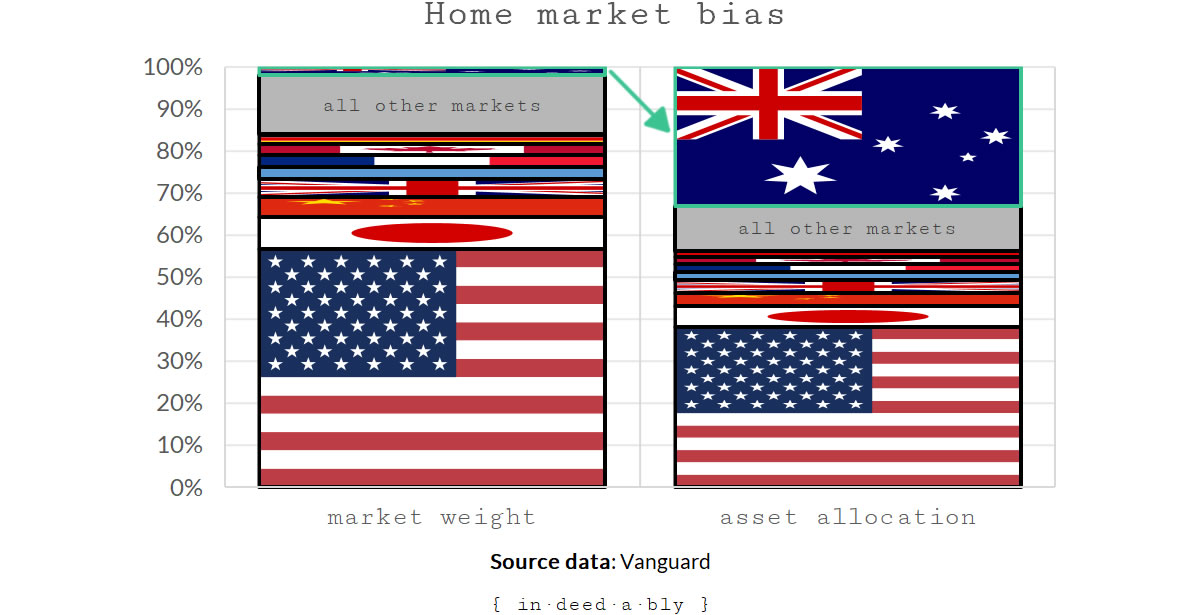

Yet the home market bias remains deeply ingrained. Financial advisors often recommending a t-shirt slogan asset allocation of 1/3 local equities, 1/3 “international” equities, and 1/3 high-grade bonds.

That creates portfolios that are jarringly incongruous.

Outsize exposure to local firms, big fish in a very small pond.

Which means local investors ride the wave during good times, their investment returns and wages linked to the same set of economic factors. When the wave crashes, rudely dumping the investor and worker alike, they experience a triple whammy.

Once in the pay packet. Twice in the pension. Thrice in the portfolio. Ouch!

All asset allocations are arbitrary and subjective. An active decision made by each investor, even if that decision was to delegate control of allocations to the global market capitalisation gods or an index composition committee.

Adopting an investing stance that is heavily weighted towards the local market is a trap. Particularly when the investor is already significantly exposed via the employment and real estate markets.

Familiarity breeds a sense of comfort and complacency. Tangible things that are close to home.

However, I wonder if we would adopt those same allocation decisions were we to step back and reframe the decision as placing a huge bet on the local economy’s ability to outperform all other markets over the investor’s time scales?

By adopting a home market bias, that is exactly what we are doing.

Redundant redundancies

My day job is running a business.

Part of ensuring that business runs smoothly is maintaining a cash reserve to act as a shock absorber for the unexpected. Ensuring obligations are met. Staff paid. Providing continuity.

In my personal finances, I maintain a contingency fund. Performing a similar function to my business’s cash reserve, providing a buffer to smooth out the ride given the lumpy earnings profile my seasonal working pattern results in.

Each country where I have invested in property, I also have access to a cash reserve. International money transfers can take a few days to clear, so holding a small cash stash to cover the occasional emergency has proven to be a prudent choice on occasion. In most cases, an offset account or line of credit is sufficient for this purpose, but unfortunately not all lending facilities are immediately accessible.

Viewing cash reserves in isolation is a trap.

Each of these discrete buckets of cash makes varying degrees of sense.

However, when viewed in aggregate all these cash holdings have a level of redundancy bordering on the ridiculous. The opportunity cost of maintaining all those separate buffers in terms of foregone investment earnings is potentially vast.

Dichotomy

Each of these case studies highlights an example where making individually correct financial decisions is isolation can prove counterproductive to achieving our long term goals.

It is only when we step back and survey our approach through a big picture lens that we start to observe the inherent conflicts or contradictions that may be present.

Individual elements of our plan working against one another.

Inefficient duplication of effort or allocation of resource.

My brief return to the world of development was enjoyable in the moment.

However, while I was contentedly torturing computers, nobody was performing my day job. Though I may not like to admit it, a dozen people in the project team could have written a better program.

Yet, none of them could do what I was supposed to be doing.

My small picture win, conscious pleasure notwithstanding, was a big picture fail.

Which gives rise to another uncomfortable question, the disconnect between my time investment decisions and my happiness!

References

- De Silva, M. (2019), ‘The art and science of stewarding the S&P 500’, Quartz

- First Direct (2020), ‘Switching Bank Accounts‘

- Goldman Sachs (2020), ‘Marcus: by Goldman Sachs‘

- National Savings and Investment (2020), ‘Premium Bonds‘

- Office of National Statistics (2020), ‘Inflation and price indices‘

- Vanguard (2020), ‘FTSE All-World UCITS ETF (VWRL)‘

John Smith 26 May 2020

I saw (and did) the same futile chase of [regular] savings accounts for less than my time worth. Masochism versus eficiency. 😉

Regarding the redundant cash reserve in various currency/countries, it depends of the level of FI(RE) someone focus. I prefer the less eficient way, because I sleep well in the night.

This is the price for my happiness. Evaluation of enough, delayed gratification. Multi-layer safety networks. Fiat money is over-valuated. I want to be healthy and poor rather than rich and ill.

[BTW: I will never be “poor”, poverty is a state of mind, Buddhist priests could confirm it]

{in·deed·a·bly} 27 May 2020 — Post author

Thanks for sharing your experiences John Smith. It sounds like you have found a path that is working out nicely for you.

ermine 30 May 2020

I found that too. I still have somewhere in the lab a frequency filter I designed soon after I started work – it was a tough one to get right, involving lots of calculation and then fiddling on a network analyser. And it was satisfying at the end because it did it’s job perfectly, fixed the problem, and I could point to it and say “I did that”. As time goes by and things get more abstract, those moments got fewer and fewer. There’s something about that close coupling of action and result that is satisfying, as Matthew Crawford described in his book shop craft as soulcraft. I experienced a faint echo of the same thing on taking a gummed up carburettor apart, cleaning it and hear the engine start. It confirmed the couple of hours was a good use of my time.

Savings accounts – I moved all of mine to NS&I Direct saver. They pay 1% so it’s not getting ahead. But it’s safer, and simpler as I already use premium bonds so I didn’t have to go through all the know your customer game again

{in·deed·a·bly} 30 May 2020 — Post author

Thanks ermine. It is fantastic you still have the frequency filter. A curiosity to the kids/grandkids when they visit, but a trophy to be proud of for you. The source code for my circa 1998 vintage Visual Basic programming masterpieces wouldn’t look nearly as impressive up on the shelf!

I too have parked my contingency fund in NS&I premium bonds, aside from a small float in a current account. Emergency expenses (i.e. having to pay at midnight on a bank holiday weekend) generally can be met via credit cards, while the rest can wait a couple of days for bank transfers to complete if necessary.