“What is a minute?” demanded the overcooked five year old. He used a forearm to wipe sweat from his eyes, shooting his best impression of his mother’s death stare at the arrivals board further down the train platform.

It was unmoved, optimistically reporting the next Piccadilly Line train was due in 3 minutes… just as it had for the past quarter of an hour.

Only half listening, I replied “A tube minute? An arbitrary unit of measurement used by TFL to describe the gap between trains”.

He turned the death stare on me. I tried again.

“A year is what we call the length of time it takes for the Earth to complete a lap around the sun.”

The arrivals board ticked over to show 2 minutes remaining.

“The Earth spins around in a circle. A day is what how long it takes for the Earth to spin all the way around.”

“The Earth spins around roughly 365 times during each lap around the sun, so there are roughly 365 days in 1 year.”

“Each day can be broken into 24 parts, called hours. An hour is roughly how long it takes you to watch 2 episodes of Transformers”.

“An hour can be divided into 60 even smaller parts, called minutes. A minute is roughly the amount of time it takes you to eat a chocolate cupcake”.

“A minute contains 60 tiny parts, called seconds. A second is roughly how long it takes you to say the word ‘hippopotamus’”.

He eyed me suspiciously for a couple of heartbeats, unsure if I was telling the truth or talking complete bollocks.

The arrivals board reported 1 minute left.

“Can I have an ice cream instead of a cupcake? I’m melting here!”

The arrivals board reset to once again show there were 3 minutes before the next train was due. Lies!

Explain time to a five year old.

The next morning at school drop off I overheard him tell his best mate that every day the Earth spins around because a hippo eats lots of chocolate cupcakes. It gets so dizzy that it wobbles around the sun all year long. Both boys then proceeded to spin around in circles, giggling, until they staggered towards their teacher like a couple of drunkards wearing wobbly boots.

Her death stare wasn’t nearly as intimidating as the boy’s.

A brief(er) history of time

Somebody smarter than me once said “if you can’t explain it to a six year old, you don’t understand it yourself”. My son’s questions about time left me challenging my own perspective of time.

The explanation I gave my son summarised roughly 4,000 years of scientific study credited to great minds like Philolaus (the Earth rotates), Aristarchus (the Earth orbits the sun), Hipparchus (dividing a day into 24 hours), and Ptolemy (dividing an hour into minutes and seconds).

Our system of timekeeping has some rough edges.

The nice reliable calendar invented by Clavius requires a uniform length of day and year. The irregularity of the Earth fails to provide the degree of rigour and precision required.

As a result we have leap years because the Earth doesn’t spin exactly 365 times as it orbits the sun. We also add leap seconds because it doesn’t take exactly 24 hours for the Earth to complete a revolution.

Another shortcoming of our timekeeping system is the importance it places on perspective.

The adoption of days and years was a convenient choice several millennia ago, when nobody possessed the technology required to worry about minutes or seconds. The living patterns of most folks saw them start the day at sunrise, have lunch around midday, and down tools as the sun was setting.

The arrival of clocks saw midday become synonymous with 12:00, from the perspective of the observer. Without the leap year and second adjustments, the time on the clock would gradually diverge from where we observe the sun.

The problem with this is that at the same instant in time that midday occurs in Paris, it will still be morning in London, and nearing midnight in Auckland!

That was fine while most people stayed in one place. However it made life difficult for sailors trying to figure out where on the oceans they were relative to home. Vespucci and Galileo looked towards the stars to find a common reference point that could be seen in both places, which partially solved the problem… but only on clear nights.

A clever clockmaker named John Harrison approached the problem in a different way, inventing a suitably resilient watch that allowed sailors to always tell the time at home.

Atoms replace the sun for time keeping.

A watch was accurate enough for use by sailors on long voyages, but improvements in transport and communication created a demand for ever more precise timekeeping. Global Positioning Systems, the internet, and electronic trading platforms all need to know exactly what time an event occurred regardless of where in the world it occurred.

The humble second was redefined as a unit of measurement by the Bureau International des Poids et Measures. They wisely chose to measure it using something slightly more reliable than the Earth’s movement (or hippos). We keep time using an atomic clock, which is said to remain accurate for more than a billion years.

Science Fiction writers including Gene Roddenberry, George Lucas, Douglas Adams and Peter F Hamilton have long dreamed of humanity exploring the stars. With Jeff Bezos, Richard Branson and Elon Musk have all investing vast sums in the development of a private sector space travel capability in recent years, it appears those dreams may soon be realised.

When that occurs the Earth-centric perspective measures of time we currently use will lose some of their relevance. The concepts of years and days will mean different things on Mars, where the number of seconds, as defined by the atomic clock, required to orbit the sun or complete a rotation differs markedly to those of Earth.

Perhaps in time a universal Star Trek style “star date” will emerge, removing the need for the current complicated system of leap year rules, time zone offsets, daylight savings, and the like.

However time is measured, it provides the context required to understand a sequence of events like cause and effect. For example, the first beer came before the fourth beer… which was followed by the hangover.

If the imaginations of those Science Fiction writers were correct time may even be a fourth dimension through which we will one day be able to travel, perhaps in a Tardis or a DeLorean. If I were a time traveller I would want a very reliable timekeeping method to get where I wanted to go.

Not enough hours in the day

Everyone has the same number of hours in a day. Image credit: pngtree.

Until spaceships become accessible to the masses, everybody is sharing the same ride on the Earth as it orbits the sun.

That means we all have the same number of hours in a day, and the same number of days in a year.

Yet every day I hear people complaining they don’t have enough hours in the day, or they are running out of time.

I concluded the simple explanation I provided to my five year old son was reasonably accurate, so that suggests these complaints are a fallacy. The problem isn’t the quantity of time, but the prioritisation of how it is invested. A case of being able to do anything, but not do everything!

Where does all that time go?

According to the OECD’s “Time use across the world” dataset the average person’s day is spent performing the activities displayed on the treemap below.

Box size represents proportion of the day spent on an activity. Left click in a cell to drill down. Right click to roll up.

To provide those figures with a rough sense of proportion, over the course of a year the average person:

- sleeps the equivalent of January, February, March and April.

- performs household chores for the equivalent of June.

- watches television for the equivalent of September.

- commutes for an entire week.

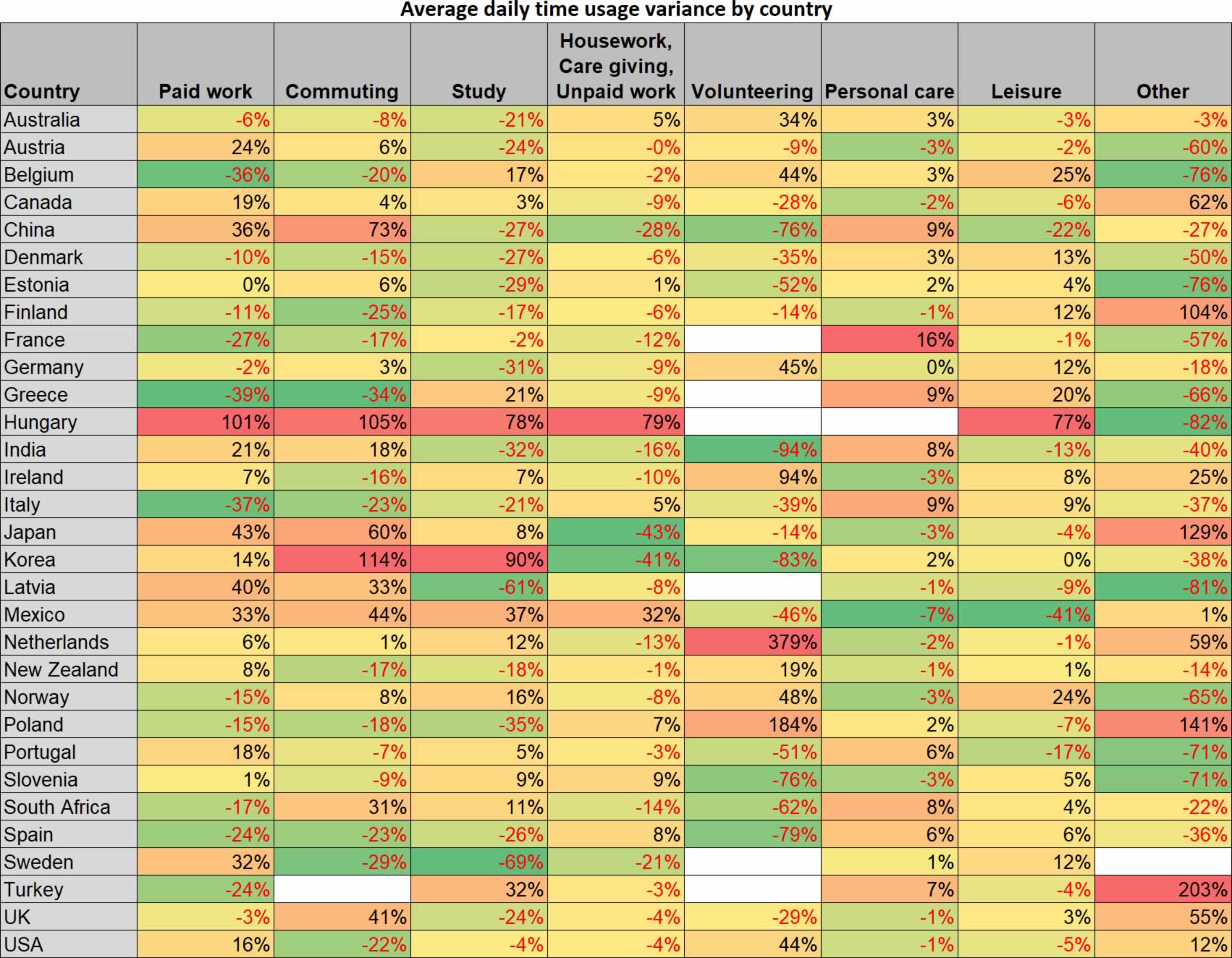

The conflicting demands on our time vary from culture to culture. How so? The heatmap below highlights the percentage variances of each OECD activity category by country.

Looking at the data some interesting cultural variances are highlighted:

- The Japanese work hard.

- The Koreans invest in themselves most via studying.

- Commuting sucks vast amounts of time in Korea, China and the United Kingdom.

- The Mexicans don’t sleep much, but spend a lot of time as care givers.

- The Dutch are huge volunteers.

Obviously your own time allocation choices will differ from those reported in the OECD. That said if your allocations vary markedly from the above then it would be worth validating why that is, and in (the case of an adverse variance) whether you should take some corrective action to your time prioritisation approach.

Less busy in 4 simple steps

How can these time poor people complete more of the things they want to get done?

The answer to this question is one of those simple, but not easy, ones:

Spend less time on low value activities, and invest your time concentrating on the high value activities.

Value isn’t just a monetary concept; it also includes enjoyment, fulfilment, or satisfaction.

Here are four simple steps to make yourself less time poor.

-

Cease doing those activities you don’t enjoy, that also don’t need to be done.

Stop wasting time on busy work.

-

Invest in yourself through study or skills acquisition to increase the marketable value of your time.

Never forget that there is a ceiling price any of us can command for our time. If you fail to ensure your living costs are sustainable within that ceiling then you are setting yourself up for a fall.

-

Apply increased earnings to time arbitrage: buy back your time.

There are many tasks that must be completed, yet not by you personally. Outsource essential, yet low value, activities that you don’t enjoy. Invest the time you save in a higher value activity.

-

Channel as much of your income as possible into investments that generate free cash flow.

Assuming constant lifestyle costs, every dollar produced by investments is a dollar you no longer need to earn by selling your precious time.

Consistent application of this approach will eventually allow you to remove the financial imperative from the decision about how you invest your time.

How quickly that process takes is largely determined by the size of the gap between your earnings and your lifestyle costs.

It worked for me, allowing me to take time out to enjoy an ice cream with my five year old son on a hot summer’s day, rather than having to stress about recalcitrant arrivals boards and uncooperative trains!

References

-

Bureau International des Poids et Measures (2014), “International System of Units“, 8th Edition

- OECD Gender data portal (2018), “Time use across the world“

1 Pingback