“That guy” strutted past our beach towels on the sand.

Wearing only an improbably small pair of white budgie smugglers and a pair of Aviator sunglasses

He bore an uncanny resemblance to a walrus. A once-powerful physique running to fat, thick shoulders and chest now competing for dominance with an impressively proportioned belly. The whole package shrink wrapped in wizened sun-bronzed skin and covered with thick dark body hair.

My lady wife arched an unimpressed eyebrow. “What is he thinking?”

“That guy” caught her expression and responded with a thousand-watt smile.

He looked preposterous and he knew it.

Embraced it.

Wore it with the swagger of a man who simply did not care.

Transcendent beyond the everyday worries of mere mortals, with their constraining self-doubts, desperate desire to fit in, and crippling fear of the unknown.

We watched as he made his away along the beach, exchanging warm greetings with women young and old as he went. Confidence personified, from huge smile to cheeky builder’s cleavage peeking out of his tiny white Speedos.

Here was a man with certainty about his place in the world.

That evening we sat at an outdoor café, enjoying wood-fired pizzas and cold beer. Locals and tourists mingled in that relaxed and carefree way that only beachside holiday towns seem to achieve.

“That guy” was seated alone at the next table. After a while, we got to talking. He was an expat who had moved to the town a few years earlier. The last of his children had grown up and moved out. Days later, his wife had left him. An ambush of sorts. No further need to “stay together for the kids”. A move she had been planning for years, unbeknown to him.

Cleaned out in the subsequent divorce. Retirement plans throw into disarray.

Suddenly alone.

Discovering that for the first time in nearly 30 years, there was no need to compromise or settle.

He had an epiphany: stop planning life and start living it.

Now he led a simple existence in a beautiful location where what was left of his money should sustain him for the rest of his days. Enjoying the warm weather. Nice food. Relaxed company.

No pressure.

No stress.

Just blissful idleness, broken up by projects and volunteering at the local food bank whenever the motivation struck. He had even taken up some new hobbies, slowly mastering the dying art of stained glass window making.

Over the years I have often thought back to “that guy”, and not just because the sight of those tiny swimming trunks still haunts me. No, it was his inspiring adaptability. Proof that our plans will change markedly throughout our lives, yet we survive and succeed regardless.

Last time I wrote that decumulation planning was a behavioural exercise rather than a financial one. Uncertainty and future change would regularly require us to adapt and refine our plans. Based on the feedback I received, my conclusions in that story made some readers very uncomfortable!

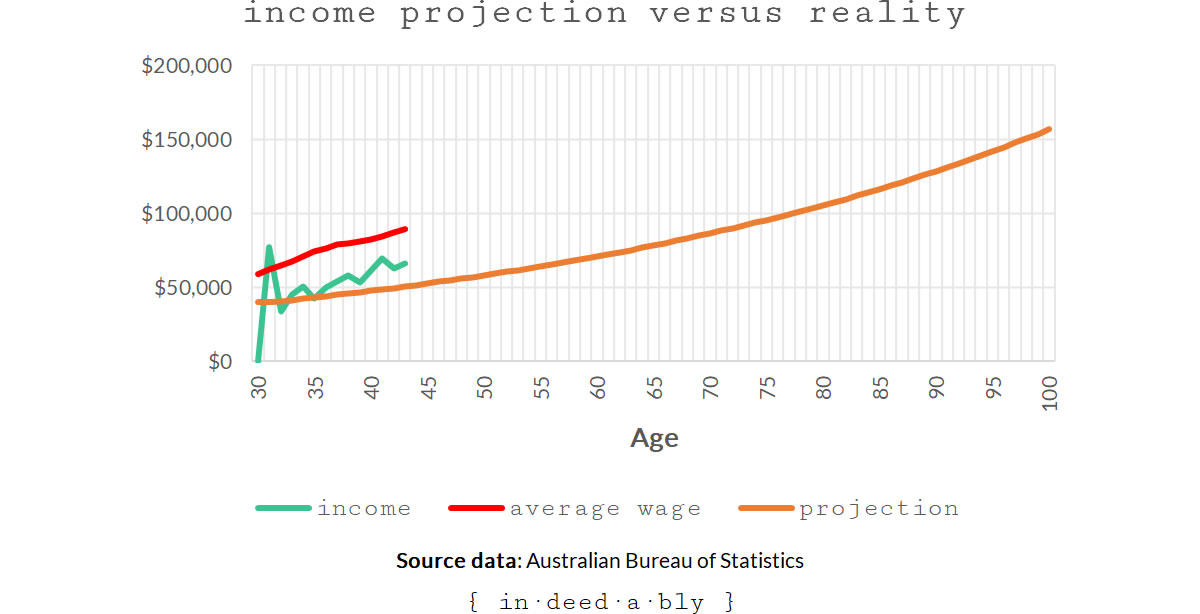

Today I thought I would illustrate my conclusion by using how my past selves had pictured their future, and evaluate how their imaginings would have worked out in reality.

18 year old me

Long ago and far away, I was an 18-year-old kid. Like many people at that age, I had big dreams and no clue. Still believing anything was possible for those who showed up and put in the work. Just beginning to learn that reality is very different.

I was about to buy my first car. Commence university. Invest in the stock market. Exciting times!

Looking to the future, I was certain about a great many things.

I would never get married. Never have children. Never turn into my parents.

I was going to escape my home town. Travel the world. Live and work overseas as an Accountant.

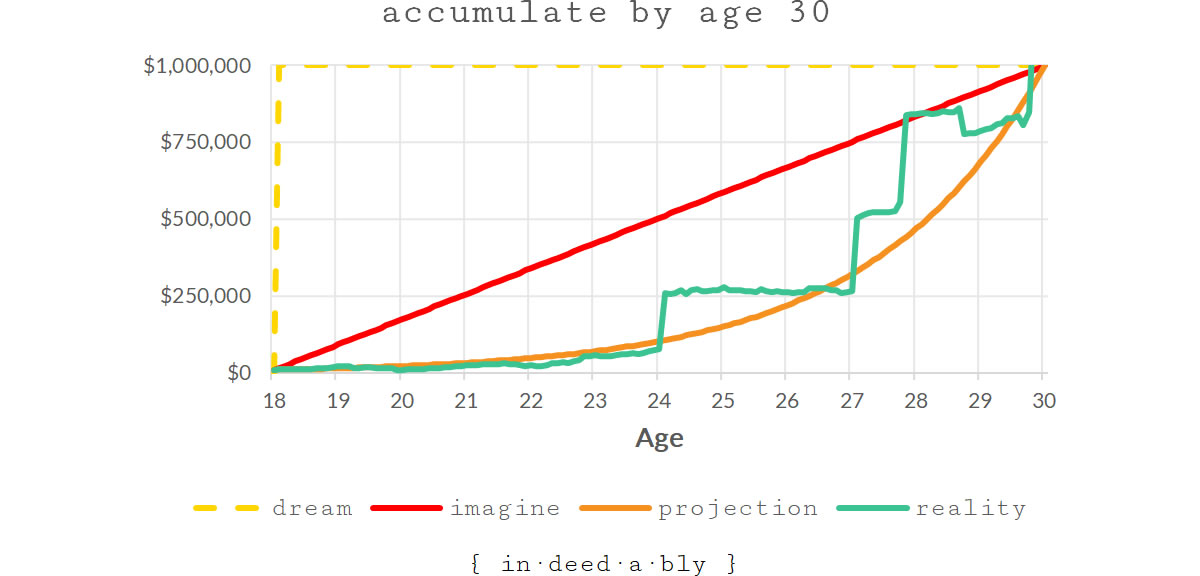

I would become a millionaire by the time I was 30 years old.

With the earnestness and ignorance of youth, I was never going to sell out. Give in. Compromise.

Armed with these personal values and roughly $10,000, I would show the world what I could do.

While the millionaire idea had initially been a childish response to being told I couldn’t do something, there was also some logic behind it.

I had read somewhere that historical long term annual real investment returns averaged about 4%.

Four percent of $1,000,000 was $40,000, considerably more than the ~$21,000 average income that single-person households earned at the time. Average income seemed like a reasonable proxy for living costs.

The “income” stream should provide a sustainable cashflow. A decumulation plan of sorts. As I had no desire to live in the middle of a busy big city, that “income” should be sufficient to provide a comfortable standard of living for the rest of my days.

I could live by the beach. Get a dog. Write a novel. Live happily ever after.

The only problem I foresaw was that growing $10,000 into $1,000,000 in just 12 years would require achieving compounding returns of nearly 40% per year! In reality, much of that capital would need to be earned and saved rather than grown. Particularly in the early stages.

28 year old me

Ten years later, I was married. Living in the middle of a busy big city, on the other side of the world.

I was running a consultancy business, and occasionally helping out as an extra Programmer when deadlines demanded it.

Far less certain about most things, but still sure I wouldn’t have children.

Any illusions that the world was a meritocracy had long since been dispelled.

I had been wrong about not selling out. Needing to pay the rent will do that to a person’s ideals.

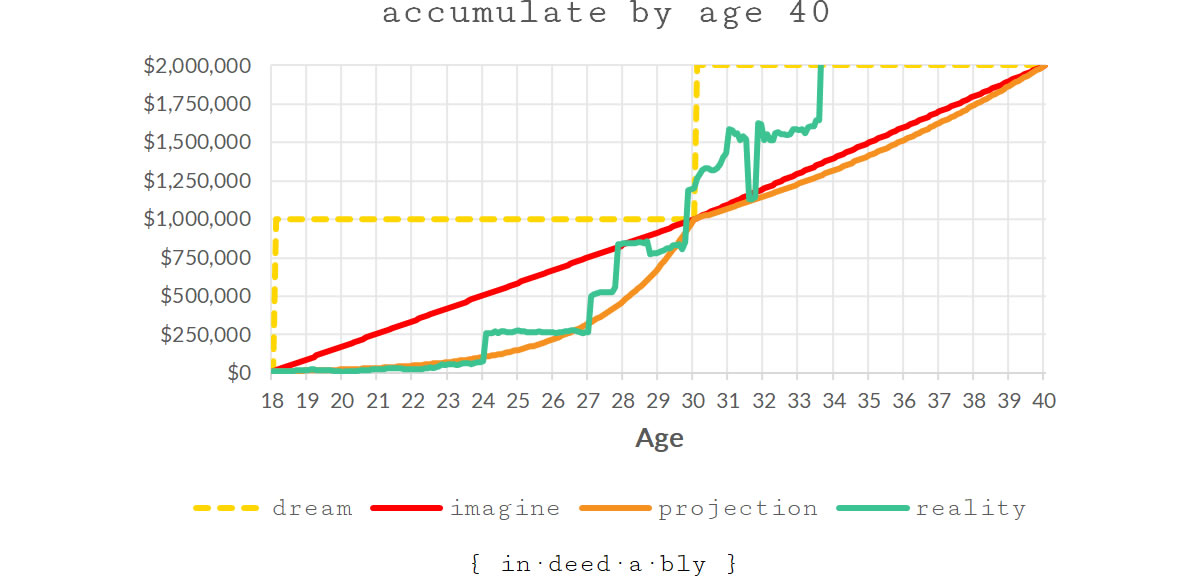

My “millionaire by thirty” goal was one of the few parts of my 18-year-old self’s plans that had survived contact with the realities of being an adult and the compromises of living with a significant other.

However, some logic errors in my initial assumptions had been brutally exposed.

I had forgotten that average wages would increase over time. A schoolboy error, obvious in hindsight.

That ~$21,000 average wage from when I’d originally set my plan in motion was now ~$55,000.

A million just didn’t buy what it used to!

It would no longer be anywhere close to “enough”, even for the uncomplicated solo existence envisaged by my younger self.

Now I was trapped on a hedonic treadmill. No matter how much I earned, it never seemed enough.

28-year-old me was bored. Frustrated. Restless. The compounding result of decisions made and avoided. I neared completion of a Financial Planning qualification, intending another career change.

On a whim some months earlier, I had entered the “green card lottery”. A life-changing diversity programme that awards United States permanent residency to the winners and their families.

I won!

For the first time in a long time, I was excited about something.

Looking forward to casting off the self-imposed shackles of routine and unsustainable living costs.

Seizing the opportunity to hit reset and make a fresh start.

My revised plan was to take up the green card, work in Boston until I had sufficient net worth to have conquered the financial imperative, then move to a beachside destination. Maybe Hawaii!

38 year old me

Another decade passed. I was still married, and back living in the middle of that same busy big city.

38-year-old me had learned that “life happens”, and nothing is certain.

I now had two kids and lived in a flat I owned mortgage-free.

I had been wrong about not having children. They proved to be the most rewarding of experiences.

Housing costs had only partially been replaced by nursery fees and nanny wages. For the first time in many years, there was a tangible positive difference between cash inflows and outflows.

Unfortunately, the flat was too small for my rapidly growing family, so the reprieve would be shortlived.

I still ran the consultancy, though changing fashions foretold the looming end of its lucrative specialist niche.

I had also been wrong about Financial Planning. After qualifying I was unable to get past the inherent conflict at the heart of the profession: what is good for the planner is rarely good for the client.

Attaining that millionaire goal was a distant memory. The first one now had a friend.

18-year-old me had made some naïvely simplistic assumptions with his plan. Projections based on smooth lines reflecting historical averages. The passage of time allowed those assumptions to be validated against lived experience.

I have extended the period covered by the remaining charts a little, to capture both the Global Financial Crisis and the first year of the COVID pandemic, which tells a more interesting story even though it spans beyond 38-year-old me’s observations. This doesn’t change the outcome.

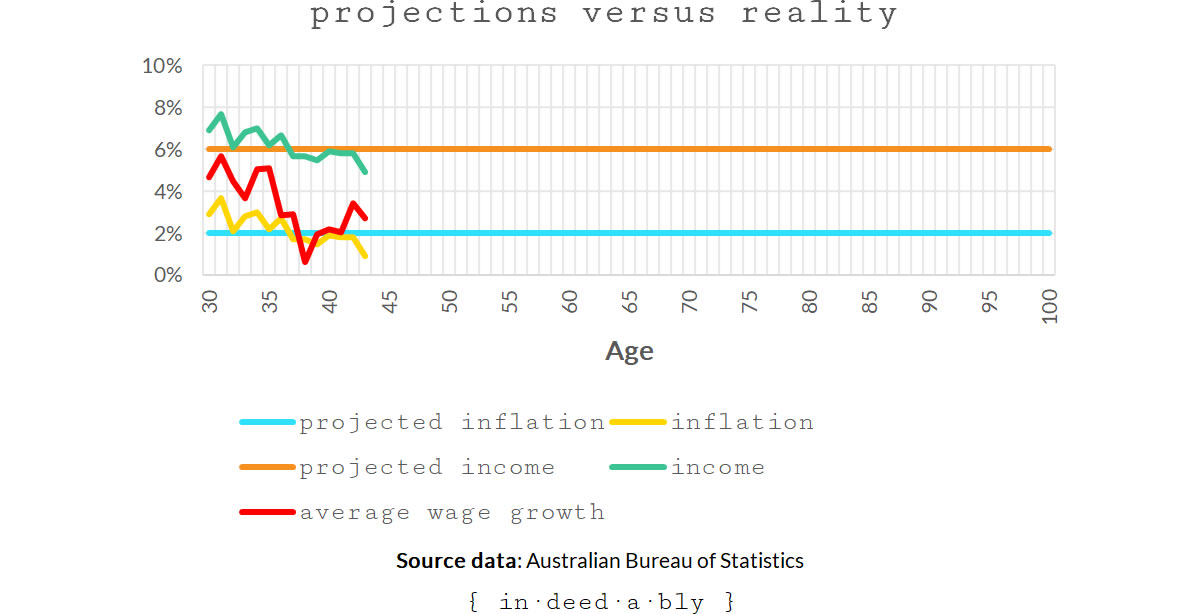

The “income” line illustrates the 4% real return assumption, using the S&P500 Total Return as a representative investment. Average wages continued to track the original comparison measure of single-member household average earnings that 18-year-old me had sought to beat. So far, so good.

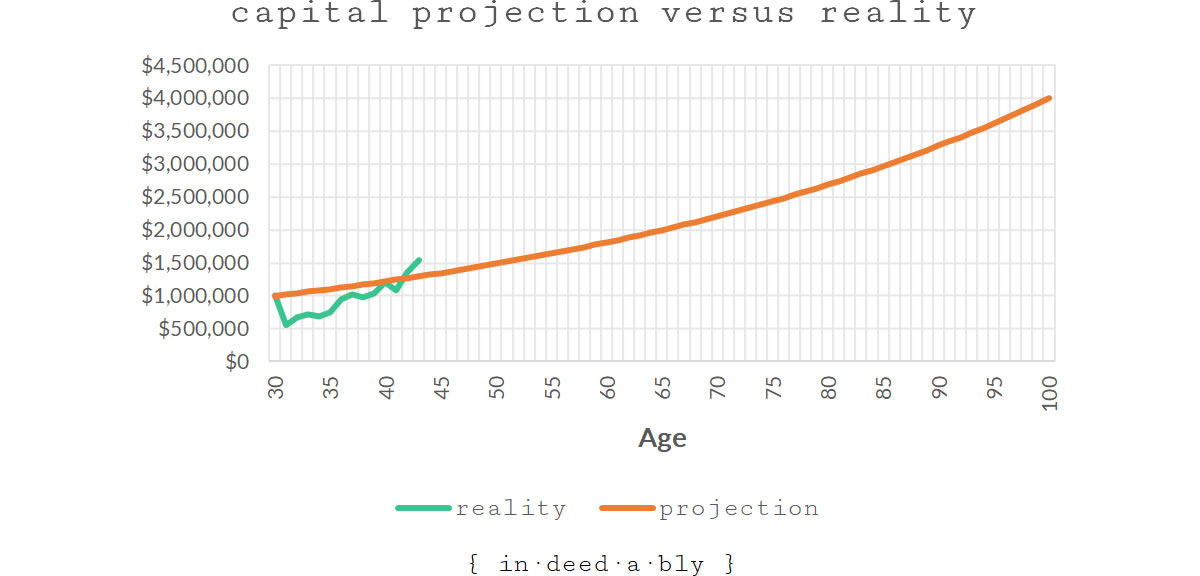

The next chart illustrates something else that 18-year-old me’s plan had not accounted for, invested capital values can go down. The impact of the GFC was swift and brutal. The decumulation plan’s annual drawdowns exacerbated the effect, a real-life sequence of returns risk case study.

It would take a record-breaking decade long bull market before my capital levels returned anywhere near 18-year-old me’s simplistic projection.

Where things get troubling is observing how 18-year-old me’s plan for derived “income” performed against average wages.

The low inflation environment of the last decade resulted in “income” falling to levels well below the average wage, where it has remained ever since. Given that average income had been selected as a proxy for cost of living, younger me would have experienced some very frugal years had he faithfully stuck with his decumulation plan.

After a slight hiccough early on, “income” growth had outpaced the projection. Despite the lower than expected capital values throughout much of the decade, the plan had so far played out largely as 18-year-old me had imagined it would.

Revealing

The interesting lesson from this exercise wasn’t how surprisingly well the decumulation plan, imagined by my naïve 18-year-old self, had faired during its first 10+ years. No doubt my overconfident younger self believed that outcome was a certainty!

In this, as in so many things, he would have been mistaken.

No, the interesting part is just how poorly suited that simple decumulation plan I cooked up 25+ years ago turned out to be at each of the subsequent life checkpoints in this story.

The major changes didn’t originate in a spreadsheet.

A Monte Carlo backtesting simulator could not have anticipated them.

They were the result of a lifetime’s conscious choices, and unpredictable “life happens” events, that combine to shape our lives.

18-year-old me wouldn’t recognise the man I am today. What the hell happened?

28-year-old me would be dismayed at where I find myself. Still doing the same job in the same busy big city, but now with kids?

38-year-old me would enviously look on, wondering where the real me had gone and who this imposter was in his place. How had he ever found the time, money, and confidence to semi-retire?

Our perspectives are framed by our experiences and priorities.

Each version of younger me would observe the same semi-retired father, husband, business owner, and migrant that I am today.

Each would perceive something entirely different.

Which raises a troubling question. After being so comically bad at predicting my own future, what makes me think the decumulation plans I put in place today for future me in 10, 20, and 30 years time will fair any better?

Or will things go full circle? Perhaps someday I become “that guy”. Fat, happy, and single by the beach somewhere.

Were that to happen, I would grudgingly have to admit that 18-year-old me was far more prescient than I give him credit for.

I wonder if they make those tiny white budgie smugglers in my size?

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2005), ‘6302.0 – Average Weekly Earnings, Australia, Nov 2005‘

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (1995), ‘6523.0 – Income Distribution, Australia, 1997-98‘

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2021), ‘Average Weekly Earnings, Australia‘

- Maverick, J.B. (2020), ‘What Is the Average Annual Return for the S&P 500?’, Investopedia

- Reserve Bank of Australia (2021), ‘Measures of Consumer Price Inflation‘

- Retirement Investing Today (2019), ‘Real life portfolio returns‘

- Slickcharts (2021), ‘S&P 500 Total Returns‘

- U.S. Department of State (2021), ‘Electronic Diversity Visa Program‘

The bludger 14 March 2021

Do you believe even “fee for service” which the only charging structure has not freed the profession from this dilemma?

{in·deed·a·bly} 14 March 2021 — Post author

Thanks bludger. The independent fee-only is a big improvement on the bad old days of opaque trailing commissions and the like. Fantastic for the ~85%* of the population whose financial arrangements aren’t complicated enough to require ongoing guidance.

The challenge is more one of misaligned commercials. A fee-only model means the planner is essentially selling a one-off product. While the real money lies in the recurring revenue streams associated with the wealth management side of the profession.

Often times, this results in a fee-only planner interviewing the client and preparing an initial plan that contains recommendations, unsurprisingly several of which will be upsells into products and services for which the planner will receive recurring remuneration.

The ongoing asset allocation and management of a self-invested pension plan might be an example. This could be as simple as some low cost trackers like those offered by Vanguard or iShares. Or it could venture into more complicated approaches that unsurprisingly require more ongoing management, churn, and generate more fees.

For some folks the complexity is warranted. For most of us however, what is good for the planner isn’t good for the client.

* figure based on the proportion of the population who don’t need to complete tax returns

FullTimeFinance 15 March 2021

This post left me with the talking heads song running through my head: “this is not my beautiful house, this is not my beautiful wife.”

{in·deed·a·bly} 15 March 2021 — Post author

Great song that FullTimeFinance, the “Wall Street” song.

Fire And Wide 16 March 2021

Budgie smugglers……builders cleavage…some lovely imagery this time…thanks for that! That guy must be firmly in the camp of people who believe “any attention is better than no attention…” ?

But hey, whatever makes you happy right! And absolutely right – we are about as good as predicting where we’ll be in twenty years as we are the lottery numbers. Both not really worth spending time (or money!) on.

I figure so long as I’ve got flexibility, I’ll see where we go. At the moment anywhere sunny is tempting though!

{in·deed·a·bly} 16 March 2021 — Post author

Thanks Fire and Wide.

At first I thought the same about “that guy“, but after talking to him I realised he just didn’t give a crap about what people thought. He was comfortable in his own skin, and that was all that mattered to him. Some people find that attractive I guess, even with the plaitable back hair!

I agree, flexibility is important. One thing this thought experiment highlights is the concept of a “magic number” (as opposed to a recurring cash flow stream) can be deceptive, as we don’t know what we are going to want to be able to do in a decade or two’s time. My kids example could just as easily be an expensive new hobby (driving racing cars or renovating a home) or significantly increased outgoings related to aged care, illness, or disability.

John Smith 17 March 2021

“Our perspectives are framed by our experiences and priorities.” Indeed! The priorities will totally change after the last kid has left the nest. Life will simplify. A good marriage will become more important than money. Especially in a rich capitalist nanny country; where social security provides safety net (medical, pension). Single person life improved by a pet (cat, dog). My experiences with my relatives (75+ age) show me that after 55-60 age (“peak”) few things (health, friends) really matter.

{in·deed·a·bly} 17 March 2021 — Post author

Wise words John Smith, thanks for sharing.

dearieme 19 March 2021

I’ve been visiting financial blogs for many years now. I’ve never seen a blogger mention putting aside money to support elderly parents. It must be the first time in human history when one can, apparently, expect not to be paying towards the living (and dying) costs one’s old, frail parents.

Maybe their parents are of a generation that got DB pensions?

{in·deed·a·bly} 19 March 2021 — Post author

Thanks dearieme

I guess this makes me special then! The first entry under the Wealth heading on my I will page since day one of this blog has been: “Earn an income independent of my parents. Be in a financial position to support my parents.”

But I do take your general point. The idea of my parents being mortal hadn’t yet occurred to my 18-year-old self when he put his plan together. That changed with a bit more life experience and maturity, another good example of how our decumulation planning needs to adapt and change with the evolving way we perceive the world.

The corollary your point is you rarely see financial bloggers admitting to biding their time waiting for an inheritance either, yet logically speaking several must be doing exactly, especially given the extraordinary runs experienced by the property and share markets over the last decade to fatten the portfolios of their ancestors.

I think the parental support thing may be cultural in part. In some cultures it is a given that the kids will support their frail parents. In others, that appears to be more optional. Hopefully, when the time comes, most people will do the right thing. It is another personal part of personal finance.

For the avoidance of doubt, the sketch plan presented here is not what I am living, it is an illustration of how some early thoughts would have played out using real data. A few readers have misunderstood that point, raising concerns about historically unsustainable SWR rates and the like. I thought it important to clarify in case anyone had misunderstood.

weenie 21 March 2021

Whenever I’ve been on a beach holiday, there’s always been that older guy in the budgie-smugglers and I never once thought about their back-story/history, I was too busy trying to erase the image of them from my memory!

I can’t wait til I don’t give a total crap what people think – as I’ve gotten older, I’ve started to care less, or perhaps I’ve just become more comfortable with myself, perhaps more confident.

But I’m not there yet, some of my decisions are still based on ‘what other people’ think, be that friends or family.

Retirement plans – as this guy has shown (and also Living a FI), you can’t plan for every eventuality or unknown.

{in·deed·a·bly} 21 March 2021 — Post author

Thanks weenie.

One thing I’ve realised as I have gotten older is nobody is watching.

Few people will notice a dodgy fashion choice, bad haircut, or geeky hobby.

Fewer still will care.

For the most part, those judgemental folks who do just aren’t worth wasting our time worrying about.

Fortunately, if we chose to, we get to leave much of that awful peer pressure stuff behind when we graduate high school. It just takes many of us years (or decades) to figure that out and feel comfortable in our own skins.

That’s not a license to go get a “job stopper” facial tattoo of course, but does mean we can sing and dance like nobody is watching… because they aren’t!

Q-FI 29 March 2021

I loved “that guy.” You had me cracking up.

Coming to your blog only recently, I’ve only gleamed bits and pieces of your past. I enjoyed getting a few more glimpses. You and I were at very different places at those age checkins. However, hitting a million by 30 and I believe the chart was showing $2M under 34 is quite impressive.

I agree with your underlying theme, that what we project never turns out to be what transpires in reality. I also see this all over the place with FI blogs. People who retire early and then seem baffled that their plans don’t turn out how they had envisioned. I’m not sure why this disconnect seems so prevalent in the FI community.

I had seen a conversation on Twitter the other day in which a popular young FI blogger was aghast that someone had suggested she might change her mind on having kids later in life. I thought about saying something but kept quiet. I knew my telling my 30 year old self how my values would change by 39 would only fall on def ears. It’s interesting how it takes time to really broaden your perspective.

Quality stuff as always Indeedably and I’m trying to play catch up this week on all the reading I’ve put off doing the move.

On a side note, did you ever end up living in Boston or the US for a time period?

{in·deed·a·bly} 29 March 2021 — Post author

Thanks for the kind words Q-FI. “That guy” levels of self confidence is something we can all aspire to!

The lifestyle decisions that others make, like having not kids or not owning a house, can be a hot button issue. We simply have no way of knowing what the drivers are. A conscious choice? A moral stand? A medical impossibility? A threatening home environment? The list goes on.

Whatever the reason(s), the outcome is the same.

It is not uncommon to hide a tragic reason behind a noble sounding excuse. Overpopulation. Humanity driven habitat loss. Climate change. The contagion of stupidity, producing legions of tinfoil hat wearing conspiracy theorists.

When the real reason may be as tragically simple as serial miscarriages or a partner who invests savings in their veins rather than Vanguard.

This is an astute observation. I can only chuckle when I picture my future self grinning in wry amusement at all the time and energy that current me wasted on existentialist angst, seeking meaning and purpose amidst the daily grind, when in the scheme of things we are all as insignificant as ants.