Twenty-something years ago I made my first international move.

The plan was simple.

Suit and dress shoes mailed to my future self, care of Poste Restante at my intended destination.

The rest of my clothes thrown into my Carribee backpack. Sell or donate everything that wouldn’t fit.

Jump on a plane, armed with a passport and a credit card. Confident in the knowledge that there weren’t many problems that could not be resolved by using some combination of the two.

The biggest hassle proved to be disposing of my beaten-up student car. A vehicle worth less than the radio it contained.

I faced the classic dilemma of someone facing a deadline, in my case the departure date of my flight.

Did I price it cheaply for a quick sale? Or price it fairly, and be prepared to wait for a buyer?

The reward of some much needed additional funds balanced against the very real risk of not having sold the car before my departure. Dodgy friends and a disapproving family meant no viable Plan B.

Being young and foolish, I chose immediate gratification. Impatience undermines financial outcomes.

Six years later I made my third international move.

The plan remained simple, though the execution had become more complex.

International shippers had replaced mailing a box. My clothes still comfortably fit in my trusty backpack, but married life had ended my ability to viably carry all my possessions on my back.

Once again, the biggest pre-departure hassle was selling my car.

A popular model. Purchased second hand, though new enough to remain covered by a generous manufacturer’s warranty.

Once again, the hard deadline of a departing flight created the seller’s dilemma of trading off expediency for financial return.

A handful of people responded to my advertisement for the car, mostly time wasters. The buyer proved to be memorable.

He was a vaguely familiar middle-aged guy with a heavy limp. A former professional footballer. Once billed as “the next big thing”, before an awkward tackle injured his knee and ended his career.

Now he made a living identifying and acquiring mispriced assets.

Buying from motivated sellers at a discount, then reselling at his leisure at a fair market price.

A simple repeatable arbitrage play, that allowed him to lead a semi-retired lifestyle.

The man had made a study of which vehicle makes and models were in high demand. He ensured that he stayed on top of pricing trends within his local market, which often differed from guide prices published in Glass’s Guide or the Kelley Blue Book.

He then sat back. Watched the classified advertisements. And waited.

Private sellers who underpriced their vehicles were his prey. He would strike quickly to snap up bargains. Then take his time to find a buyer willing to pay a better price, often in different cities experiencing greater demand.

His profits derived from pricing disparities. Created by some combination of ignorance and urgency.

While we haggled over the price, the man told me two things that have stuck with me over the years.

Firstly, that everyone has a price and everything has a fair market price.

While often similar, a well-informed buyer profits from being able to recognise the potential for the latter in products offered at the former. The greater the difference, the better the return.

Secondly, that life is uncertain. We are all only one bad tackle away from having our hopes, dreams, livelihood, or mobility taken away in an instant. Contingency plans are important, but we should consciously seek to enjoy the present more than we worry about future unknowns.

After mentally running through the alternative uses for the time I had remaining before jetting off, I accepted his offer for my car so I could spend more time with the friends I would soon leave behind.

Less than I had advertised it for.

More than I had expected to get.

In hindsight, the man took advantage of me. He was better informed about the fair value of the asset. He enjoyed the luxury of time. Able to wait for a buyer willing to meet his asking price.

It was no accident that he had positioned himself in a strong buying position.

Everything has a price

I was reminded of my car selling challenges this week when I received a brochure from a firm claiming they would purchase any property in the United Kingdom. Fast. And in cash.

It was a bold claim, that immediately raised some questions about how fair the offer price could be?

The sellers would face that same expediency versus financial return dilemma, resulting in them accepting a discounted price for their property in return for the certain cash on offer.

Yet I could see how it might appeal to a motivated seller. Someone who was out of work, savings, and other options. There are more than a few people who currently find themselves in just such a situation, as the effects of the pandemic ripple throughout the economy.

The average conveyancing process for a private treaty property sale in England takes 12-16 weeks.

An eternity to wait if your kids are hungry. Bailiffs are circling. Red letters arriving in the daily post.

A glacial pace to traverse the archaic, duplicative, expensive, inefficient, shambolic, often corrupt and always uncertain system of property ownership transfers in England.

Gazumping.

Gazundering.

Lenders withdrawing financing.

Multiple layers of title.

Purchase offers made on a whim, then rescinded without penalty.

Sales chains, endlessly plagued by collapse and delay.

Contrast that average time frame and contract certainty of some comparable jurisdictions such as New Zealand (3-4 weeks), Australia (4-6 weeks), Scotland (4-8 weeks), or Singapore (8-12 weeks).

The idea of algorithm-driven property price estimates is hardly unique. Every couple of years a new start-up, hedge fund, or property portal has a go at it.

All driven primarily by recent “comparable sales”. With very mixed results.

Current examples include Domain and RealEstate.com.au in Australia. Hometrack and Zoopla for the United Kingdom. OpenDoor and Zillow focusing on the United States.

The business behind the advertising brochure relied upon motivated sellers initiating contact with them. A self-selecting customer base, similar to those preyed upon by loan sharks and payday lenders.

That got me thinking. What might the equivalent of those car price guides look like for property? How might we pair data analytic smarts with the ex-footballer’s approach of seeking out mispriced assets?

Unimproved land value

Property prices, much like my car selling experiences, are determined by what a seller is willing to accept for the property and what a buyer is willing to pay for it. More psychology than science!

What constitutes fair value for a property is something that can be approximately calculated.

There are two key elements: the location of the land, and what people do with that location.

One of the jurisdictions where I own several properties abolished stamp duty a few years ago. The arguments in favour of the change were many. It was a regressive tax, Added significant friction and expense to property ownership transfers. Provided an unpredictable revenue stream for governments.

A value-based land tax was introduced in its place.

Difficult to evade.

Predicable.

Recurring.

Universal.

Calculated based upon the rolling average unimproved land value over the past few years.

Think about that for a moment. Properties taxed upon the potential usage of the land, as opposed to what it might currently be used for today. Seeking to align behaviours with profit motives. Circumventing much of the NIMBYism that holds back progress as cities seek to evolve and grow.

Every year the government calculated an estimated unimproved land value for every property.

Each valuation took into account both the location of the land, and also what permissible usage it may be put to under local zoning and town planning guidelines.

They also had to factor in all things that may have a material impact on land values.

Crime statistics.

Conservation area or heritage listing constraints.

Environmental concerns such as contamination, pollution, and risks of fire or flood.

Proximity to community facilities, employment, healthcare, and shopping.

Public transport access.

School catchment areas.

Traffic volumes.

By focusing on the unimproved block of land, rather than the buildings it may contain, the valuation was relatively objective. Eliminating many property-specific subjective elements from the equation, such as age. Character. Decoration style. Dwelling size. Floorplan layout. Form of title.

The local government treated this information as Open Data. It provided convenient tools to allow interested parties to freely filter, search, sort, and map the unimproved land valuations. Providing a useful baseline upon which property asking prices could be compared and evaluated.

Construction costs

The next element of property valuations are the buildings constructed upon that unimproved land.

When we insure a property, the insured value is not the price it would fetch on the open market. Rather, it is the cost of restoring a functionally equivalent replacement building on the block of land.

Think about that for a second. Do the cost of materials required to construct a traditional semi-detached single-family terrace house really differ all that much between locations in the same city, county, or state?

Identical building materials.

Equal numbers of bricks and roof tiles.

Fixtures and fittings all the same.

Requiring a consistent mix of skills, experience, and man-hours to complete.

There may be some regional variation in the labour costs for the builders, particularly after Brexit. Supply and demand.

Possibly price gouging, charging a “London tax” markup on materials in higher-earning locales.

Ultimately however, the raw materials of a construction project should cost comparable amounts, regardless of location.

This is bourne out by the renovation cost guides published by the likes of the HomeOwners Alliance, RealHomes, or the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors. National figures, with minor localised variations.

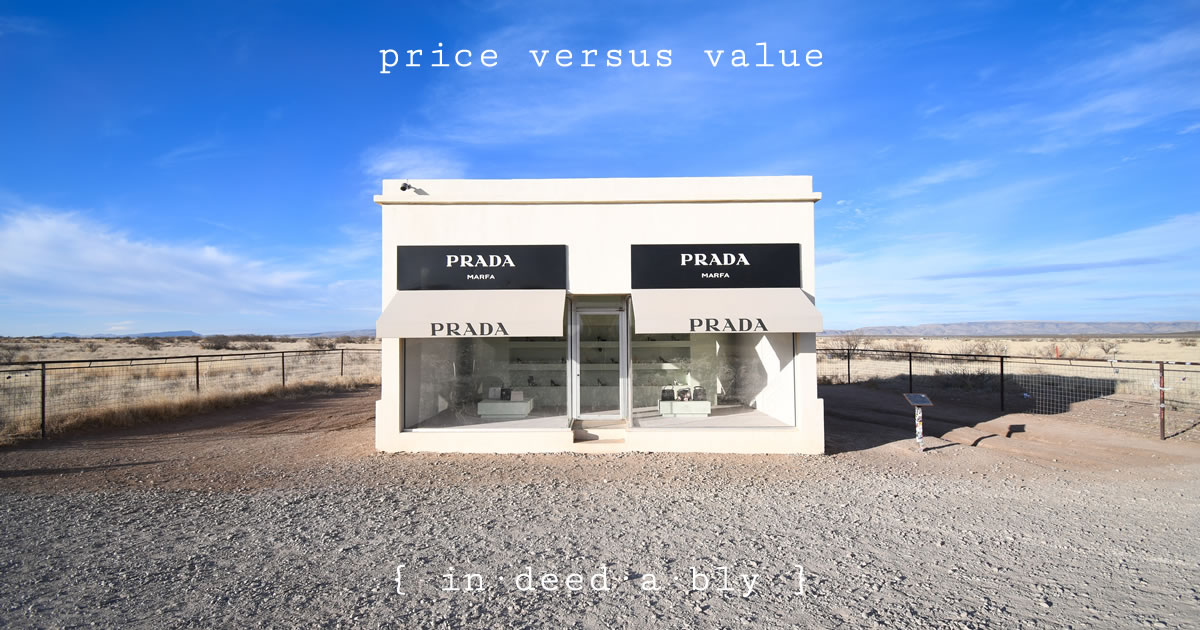

Price versus value

If we combine the unimproved land value with the replacement construction costs, then we arrive at a rough and relatively objective measure of fair value for a residential property.

Then we can use that measure to test how cheap or expensive the asking price of a given property appears to be.

Stripping out the fashion, herd behaviour, and wishful thinking embedded within the prevailing comparables based valuations.

Allowing us to assess the difference between fair value and the market price, in much the same way my car buyer was able to identify mispriced assets by comparing asking prices to guide prices.

Helping us to identify pricing disparities for further investigation.

This approach offers an alternative to the finger in the air “recent comparable sales plus 5%” valuation approach so widely used today. It won’t change the prices achieved, but does highlight the (often vast) differences between price versus value.

It would be nice to believe that prices were anchored to some quantifiable tangible value. Except this is a faulty premise. Psychology plays a larger part than many of us would be comfortable admitting.

Providing the asking price is close to what others have recently paid for an equivalent asset, people choose not to ask themselves whether that price represented real value.

References

- Aikman, I. (2019), ‘Buying a house in Scotland’, Which?

- Autovista Group (2020), ‘Glass’s Guide‘

- Home Owners Alliance (2020), ‘House Renovation Costs‘

- Home Owners Alliance (2020), ‘How long does conveyancing take?‘

- Kelley Blue Book Co Inc (2020), ‘Kelley Blue Book‘

- LegallySmart (2020), ‘What is conveyancing?‘

- RealHomes (2020), ‘House renovation costs: how much does it cost to renovate a house?‘

- New Zealand Now (2020), ‘Buying or building a house in New Zealand‘

- Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (2020), ‘BCIS Price Books‘

- Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (2019), ‘Comparable evidence in real estate valuation‘

- Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (2020), ‘Red Book Global – Basis for conclusions‘

- WhichRealEstateAgent (2019), ‘Conveyancing Costs – 2019 Fees By State‘