“Employees create wealth for their employers, rather than themselves. Tenants perform a similar function for their landlords, subsidising holding costs while the owner retains any capital growth.

What if there was a way for tenants to share the benefits of ownership during their occupancy?”

This is a thought experiment in the style of those proposed by SavingNinja. The one thing asked of participants is for a stream of consciousness outpouring of thoughts rather than a carefully polished article. Here goes…

The house always wins

Kate rents a beautiful flat, located a stone’s throw from a verdant oasis of calm in the middle of an otherwise hectic city.

She works at a university, centrally located amidst embassies, concert halls, and museums.

Every morning she rolls out of bed, jogs a leisurely five-kilometre route through the park, and arrives at the office high on endorphins and armed with a steaming hot bucket of caffeine.

Kate loves her job, and dreams of living and working in the area forever.

However, there is just one problem.

During the five years Kate has occupied the flat, its value has increased by 50%.

Over that same period Kate’s wages have not increased at all. After taking inflation into account, today’s experienced Kate has less purchasing power than novice Kate had half a decade ago.

Then Kate had rented because prices were just outside her reach.

Now she doesn’t stand a snowball’s chance in hell of buying!

This story is hardly unique. Variants are discussed daily at water coolers and social gatherings all over the city.

The deck is stacked.

The game is rigged.

The house always wins.

Everything is negotiable

Kate’s story got me thinking about the various forms of property occupancy models, and who pays for what.

At one end of the spectrum are private tenants like Kate.

Saved from maintenance expenses (but not the associated hassle) at the high cost of forgone capital appreciation.

At the other end of the spectrum are commercial landlords.

Retaining all the benefits of ownership, while the bulk of the property operating costs are borne by the tenant.

Initial fit-out.

Non-structural maintenance.

“Making good” to restore the property to its original condition at lease end.

Commercial tenants pay for it all.

In practice, the demarcation between what is paid for by landlord and tenant varies lease by lease.

Some arrangements are similar to Airbnb. The landlord provides the furnishings and pays the bills.

In other cases, such as a long term house proud council housing beneficiary, the tenant may pay for decorating and appliances themselves to ensure they get what they want when they require it.

The constants are that operating property costs money, and everyone needs to live somewhere.

Everything else is negotiable.

Some assembly is required

Governments often live beyond their means, with expenditures exceeding tax revenues.

They fund the shortfall by the selling bonds, borrowing from the public to finance the spending gap.

This is a scaled up version of an individual who spends more than they earn today, using consumer debt to cover the difference, and worrying about how to pay it all back sometime in the future.

Leverage can be a powerful tool when the return on investment exceeds the borrowing costs, or a costly mistake when it does not.

Brokers buy up these bond issues, break them down into their constituent parts, and repackage them as new investment products.

One such product is Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal of Securities (STRIPS).

First the broker “strips” the interest element from the principal element of a government bond.

They then sell the principal element as an appropriately discounted fixed term zero coupon bond.

Investors purchase STRIPS at the discounted price and receive the full principal value upon maturity.

A 10-year government bond could be packaged up into a multitude of STRIPS with varying maturity dates and discount rates.

The interesting thing about STRIPS is the way that interest payments on the original debt are separated from the capital repayments. This allows investors to pick and choose the type of investment that is best suited to their goals, timescales, and risk profile.

One investor may purchase the cash flow stream of the regular interest payments.

Another may purchase the discounted capital component that will be repaid upon maturity.

Either or both elements can potentially be traded multiple times throughout the life of the bond.

The financial crisis that led to the Great Recession was in large part caused by similar financial shenanigans. Mortgage debt was reconstituted into all manner of new investment products.

History teaches us that ended in tears. Austerity. No pay rises for Kate during her five years of work.

Risk and reward

A government bond is a debt instrument, not all that different from a residential mortgage.

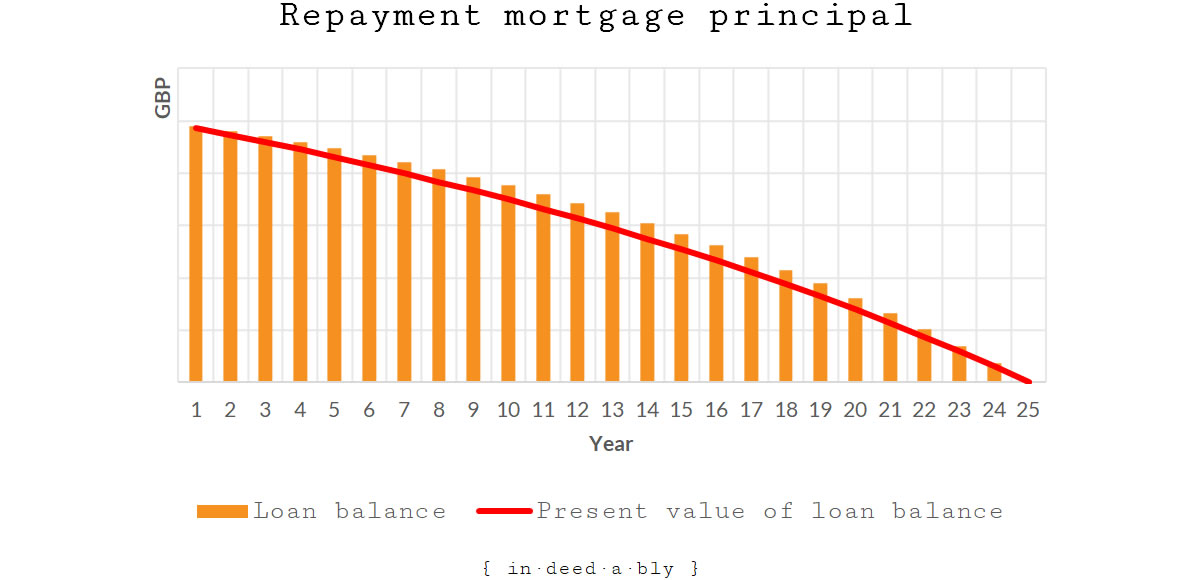

At the beginning of a typical repayment mortgage, the owner “owns” little and “owes” a lot.

Over the life of the mortgage that balance gradually shifts.

By the mortgage period end, the owner “owns” the entire property and “owes” nothing.

The real value of the loan principal is eroded by inflation over the mortgage term. The nominal amount to be repaid remains unchanged, but its purchasing power has been considerably reduced.

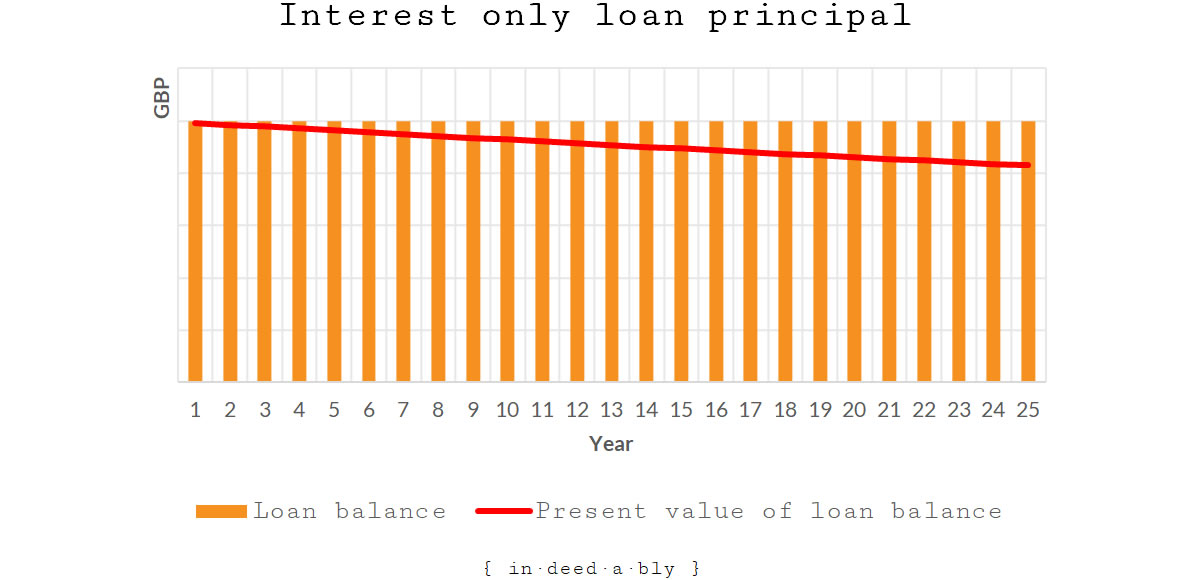

A simpler form of mortgage is interest-only variety.

A series of interest payments over the loan term, without any pesky regular capital repayments.

At the conclusion of the mortgage period a one-off repayment of the entire loan principal is made. Often funded via the sale of the property.

Whatever form the mortgage takes, the bank takes a risk by extending the loan to the owner. The bank is rewarded with the income stream of regular interest payments throughout the life of the loan.

Throughout that period the owner enjoys all the benefits of ownership, including potential capital appreciation of the property. This growth may be caused by value creation activities undertaken by the owner, or simply the result of a rising property market.

Financial alchemy

A lender transmogrifying mortgages into new and exciting financial products wouldn’t help Kate.

But what if her landlord were to perform some financial alchemy?

Imagine that Kate’s landlord created a limited company to purchase and operate her flat.

The company obtained a 25-year interest only mortgage to finance the purchase, demonstrating that the rental income was more than sufficient to cover the financing and operational costs.

A sustainably self-funding business in its own right.

This is an increasingly common ownership arrangement for buy-to-let properties, as financing costs are still tax-deductible expenses for corporate property owners, but not for private landlords.

Same property.

Same lending terms.

Same tenancy agreement with Kate.

Now let’s take some creative license, this is a thought experiment after all!

Kate’s landlord turns out to be of the benevolent variety. An exotic breed, rarely observed in the wild.

The landlord loves the fact that Kate is the poster girl for the perfect tenant:

- Isn’t running a meth lab or a brothel out of the flat

- Hasn’t sublet it as an Airbnb or taken in lodgers

- Treats the property like her own

- Pays the rent on time and in full

- Doesn’t complain

They feel bad that Kate has been priced out of the market, that is no fun for anybody to experience.

They also respect that Kate is committed to remaining in the neighbourhood for the long term.

Creating something from nothing

The company that owns the property is running a buy-to-let business, which is dependent upon the recurring rental income stream to cover its finance and operating costs.

Originally, the landlord planned to sell the property at the conclusion of the mortgage, pay off the loan, and settle any outstanding capital gains tax owed.

Any remaining funds would fatten the landlord’s wallet, making the investment worthwhile.

What if there was a way for the landlord to achieve that same outcome, while also helping Kate?

The landlord channels their inner broker and performs some financial alchemy.

The company issues some STRIPS style zero-coupon discounted debentures.

In aggregate, the face value of those debentures equates to the principal of the loan, plus the landlord’s anticipated capital growth. They are running a business not a charity after all!

The debentures issued by the company are of the convertible variety.

This means the debenture holder has the option to either convert them into equity, or receive the full face value upon maturity.

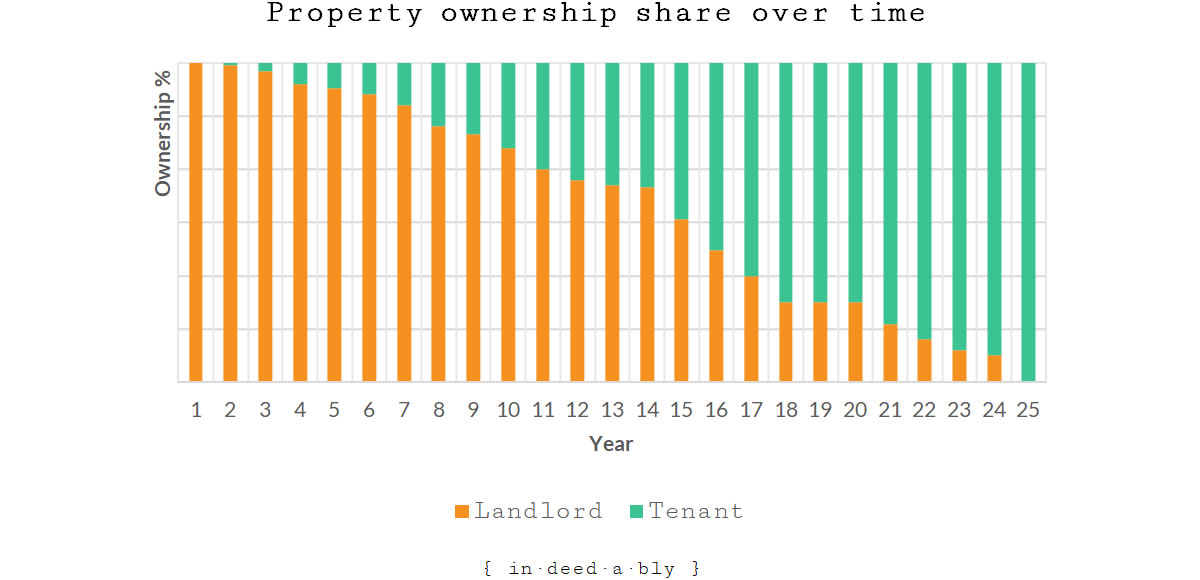

If converted, each debenture grants ownership to a single share in the company. The landlord has created 300 debentures, each one representing a single month of the life of the mortgage.

The landlord extends Kate the invitation to purchase the debentures as and when her finances allow.

Kate cannot afford to buy the whole flat. Maybe she can afford to buy slices of the property?

Each debenture Kate purchases, and converts to equity, grants her ownership of 1/300th of the flat. As each Class ‘B’ share is issued the landlord’s shareholding is slightly diluted.

To protect their own interests, the landlord holds a Class ‘A’ share that possesses 49% of the company voting rights. The debentures convert into Class ‘B’ shares that grant equity, but not control until all 300 have been purchased and converted.

The chart below illustrates an example scenario of Kate purchasing and converting debentures whenever she is financially able.

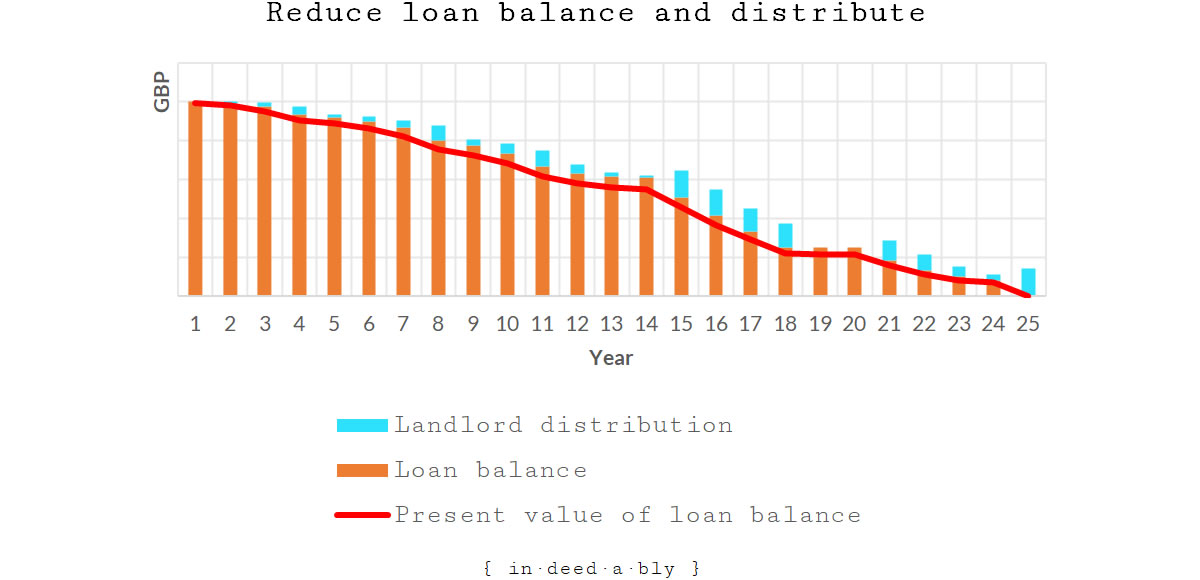

The converted debentures provide the landlord a means of locking in their anticipated future capital gains.

Part of the discounted debenture price would be used to make early mortgage principal repayments. The lower outstanding balance reduces the recurring interest payments due on the loan.

The company’s cash flow and profitability both improve as a result.

The remainder, representing the anticipated capital gain, would be distributed to the landlord. This is their reward for making the property investment.

The following chart extends the scenario portrayed above, illustrating the outstanding loan balance as Kate accumulates and converts debentures. The blue bars represent the distributions to the landlord.

What could possibly go wrong?

If the arrangement worked perfectly then it would provide a win/win outcome for Kate and the landlord.

Kate would gradually purchase and convert all the debentures, resulting in her owning the flat outright by the end of the loan period.

The landlord would have realised their desired capital growth return from the property investment.

A more likely outcome is Kate purchases and converts some, but not all, of the debentures. She ends up owning only part of the property by the end of the loan period.

The company is still obligated to pay off the remaining mortgage principal.

The mortgage could potentially be refinanced and extended.

Kate may be able to obtain a loan to allow her to buy out the landlord’s remaining holdings.

Either way, there is uncertainty.

The landlord’s investment timescales were for the duration of the original loan. They may not be interested in continuing to hold the investment. Exiting may require selling the property to pay off the mortgage, and splitting the remaining equity based on the landlord and Kate’s equity holdings.

The arrangement is certainly not without risk.

If the property prices do not rise as the landlord expects, Kate will have overpaid for her portion of the flat.

Should the property price fall rather than rise, then the company would face insolvency. Its debts exceeding the value of its assets. Both Kate and the landlord would potentially lose their investment.

By retaining the majority voting rights, the landlord has the potential to act contrary to Kate’s interests.

For example, they may decide to follow the private equity playbook: strip the company of its assets, load it up with debt, and attempt to sell it on to a “larger fool” before the house of cards collapses.

A large portion of Kate’s net worth could become trapped in an illiquid investment, that would be difficult to sell. There is not ready resale market for a partial share of a debt-laden company, whose only asset is a single residential property.

Reinventing the wheel

In some aspects, this approach resembles what the Americans call “seller finance”, which is a mortgage issued by the seller rather than a bank.

The main difference is the flexibility, with Kate able to purchase the debentures whenever she has the means, rather than having to make scheduled repayments.

There are also some similarities to the spate of crowdsourced collective property schemes that have recently sprung up in the United Kingdom.

However, Kate is accumulating slices of ownership in the property she intends to permanently occupy, as opposed to units in a diversified property portfolio.

Finally there are some similarities with the government’s “help to buy” shared ownership model. That program is only available to first home buyers seeking to buy in areas outside major metropolitan centres.

By the end of the thought experiment, my conclusion is that the convertible debenture approach might work in a select few circumstances, but is generally more trouble than it is worth.

If Kate could afford to purchase all the debentures within the mortgage term, then she would likely be able to afford a traditional mortgage that comes with fewer strings attached.

If not, then the degree of commercial flexibility and patience required from the landlord would be rarely seen outside of a tenant’s immediate family or a vote buying government subsidy.

In those cases, there would probably be less onerous methods available to gradually transfer ownership from landlord to tenant.

The unfortunate truth is that Kate simply can’t afford to buy in her dream neighbourhood without external assistance.

The market doesn’t care whether one person’s dreams are crushed by the basic laws of supply and demand which determine property prices and rents.

References

- Chen, J. (2019), ‘Convertible Debenture’, Investopedia

- HM Government (2019), ‘Shared Ownership‘

- Kagan, J. (2019), ‘Seller Financing Definition’, Investopedia

- Millar, S. (2016), ‘5 things to remember as a commercial landlord’, RealCommercial.com.au

- Morningstar (2015), ‘How Do STRIPS Work?‘

- Morningstar (2015), ‘Why Are STRIPS Popular?‘

gettingminted.com 18 July 2019

I think Kate needs a collapse in the property market perhaps resulting from much higher interest rates.

{in·deed·a·bly} 18 July 2019 — Post author

Thanks GettingMinted.

Property market “crashes” may indeed help Kate, but they don’t tend to come around very often.

She could be waiting on the sidelines for a decade or more before prices significantly pulled back. Even then, there is no certainty they would eventually fall below where they are today.