Numbers are funny things. Precision providing the illusion of certainty in a very random world.

The other day, my younger son announced that the universe was 13.77 billion years old. Not 13.76 billion years. Nor 13.78 billion years.

How did he know? It was in a fact book he had been reading during a rainy lunch break at school.

Not to be outdone, my elder son looked up from the biology textbook he had been revising. He declared the average human female is born with over one million eggs. The average male launches one hundred million little swimmers with every happy ending.

He gave an evil smirk when his younger brother innocently asked what was a happy ending?

Using my parenting superpowers, I deftly changed the subject by challenging the elder boy to calculate the probability of his existence.

The boy made grossed-out vomiting faces at the thought that his parents may have once had sex. Then he tapped some numbers into his calculator. Looked puzzled at the results. Tapped some more. Cautiously responding “1 in 100 trillion?”

While he worked, I asked the younger boy what the odds of his elder brother’s continued existence might be, were their mother to discover he had left studying for his science test until the last minute?

The younger boy chortled. “Not good!”

That night, I reflected on the boy’s maths. The vanishingly small odds he had calculated made winning the lottery look like a dead certainty by comparison. Yet he had massively uncooked his figures. Thinking about it, equally long odds would have applied to the existence of every one of his ancestors, stretching back untold thousands of generations, to a time we were single-cell amoebas doggy paddling across a puddle of primordial ooze.

Numbers quickly surpassing our ability to comprehend them.

Probabilities so small they resemble miracles.

As with my younger son’s pronouncement about the Earth’s age, that mathematical precision provided the illusion of certainty in something that was essentially unknowable with any reasonable degree of confidence.

We blindly accept headline figures such as these. Spare little thought about what they mean. “Interesting, but irrelevant” facts, like so much financial market commentary. Unactionable trivia.

For almost all of us, generalisations that are quickly arrived at and simplistic will prove sufficient. The Earth is ancient. The odds of any of us existing to read this story are vanishingly small. So what?

Longevity

Every day we hear headline figures reported in the news. At the time of writing, life expectancy at birth in the United Kingdom was said to be 79 years for boys. 83 years for girls. Which is interesting.

Compare those figures to the life expectancy at birth figures from 100 years ago, and the story becomes intriguing. 56 for boys. 60 for girls. An increase of over 40% over that period. Does that mean babies born one hundred years from now might be expected to live until they are 110 for boys and 116 for girls? Today’s statistical outliers becoming tomorrow’s normal experience? I wouldn’t rule it out.

But here is the thing. We weren’t born today. We were born decades ago. Apart from highlighting a heartening story of positive progress, there isn’t much we can do with that life expectancy at birth figure.

However, if we dive into the datasets beneath those headline figures, we soon discover some more useful numbers that can help us define some parameters for our own future plans.

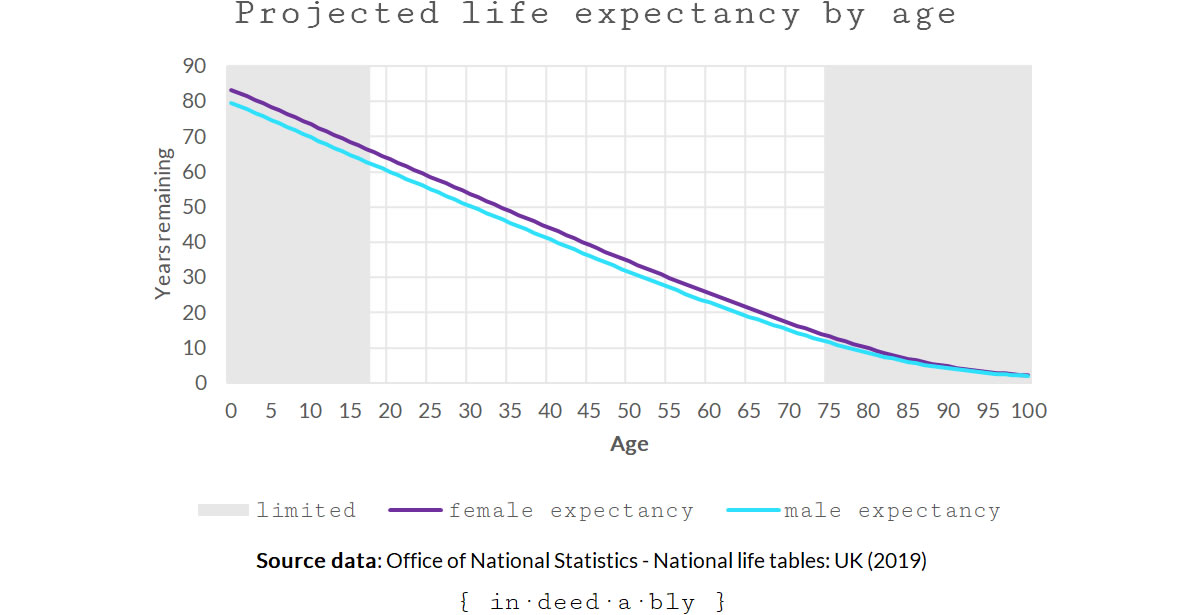

The first chart displays projected life expectancy remaining. This is useful because it looks at how things played out for those who had already survived to a given age. For example, someone aged in their mid-thirties today has already successfully run the gauntlet of infant mortality, teenage experimentation, and the overconfident sense of immortality possessed by a twentysomething.

I’ve shaded the childhood years and those from the age of 75 onwards as being limited. Periods when we may not enjoy as much freedom or control as we might like. We occasionally hear awe-inspiring stories of someone running ultramarathons or climbing Kilimanjaro in their 90s, but far more people in their mid-70s complain about how the effects of ageing clipped their wings and slowed them down. Arthritis. Cognitive decline. Diabetes. Illness. Injury. Loss of flexibility, movement, stamina, and strength. Their bodies starting to wear out after decades of fun and adventure.

In my case, the chart suggests I am probably past the halfway mark in life. More of life’s journey visible in the rearview mirror than lies ahead. However, life contains few certainties. Only probabilities.

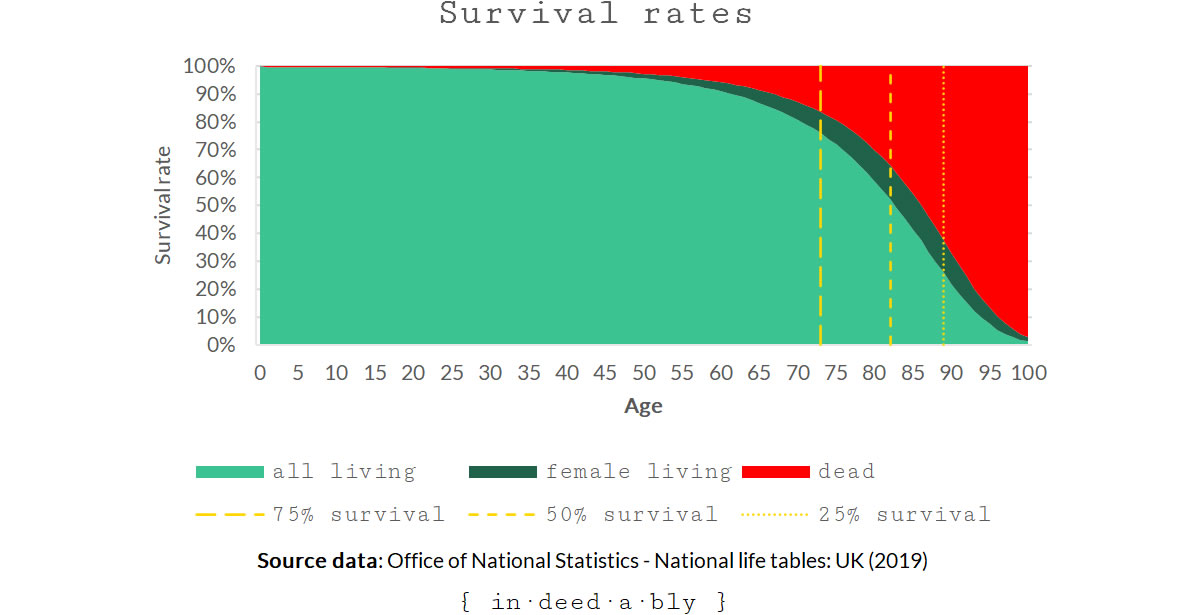

The second chart illustrates those probabilities. The green shaded area displays the population proportion who survived to a given age. The dark green stripe highlighting that girls often outlive boys.

Now the story behind those headline figures starts to get exciting.

Three-quarters of boys make it to their 74th birthday.

Half get to celebrate turning 83.

A quarter survives to the age of 90.

Nearly 1% of the population receive a 100th birthday card from the Queen.

For girls, those quartile boundaries are even higher. 78, 87, and 92 respectively.

Think about that for a moment. Despite all the doomsaying that we hear every day about accidents, disease, disaster, suicide, and violent crime, we have a 50/50 chance of becoming octogenarians.

A 1 in 4 shot of attempting to blow out 90 birthday candles.

At least one passenger riding in every packed peak-hour train carriage will live to reach triple figures!

Those are non-trivial odds. Numbers that our financial planning must take into account.

Living arrangements

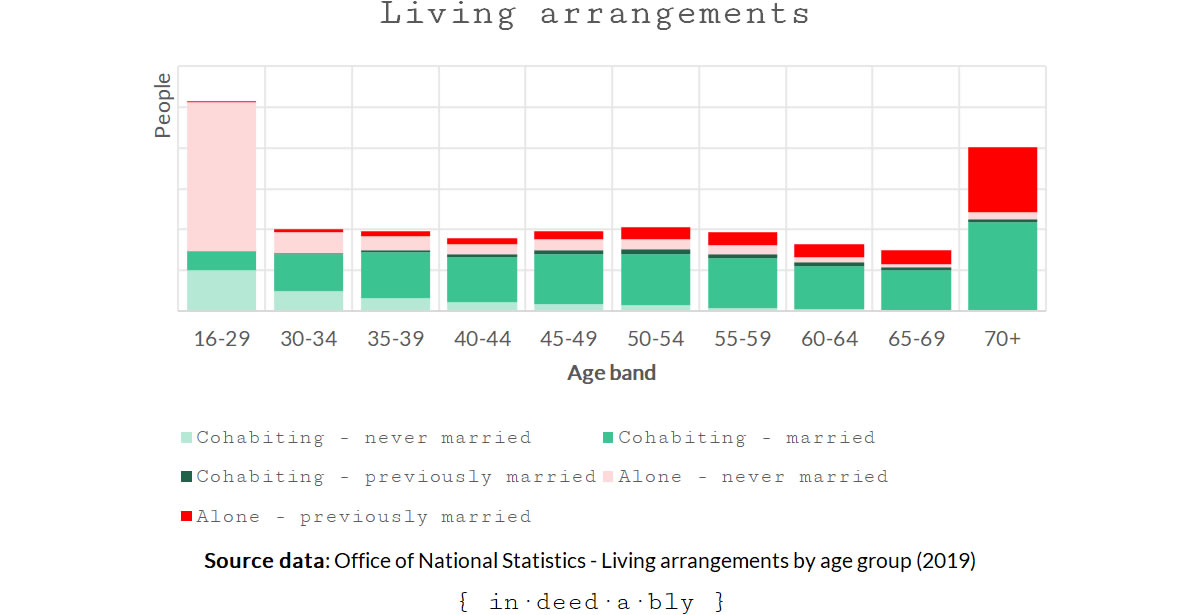

Another headline figure that we sometimes hear quoted is that roughly 60% of adults cohabit as part of a couple. Sharing living costs. Household chores. Possibly incomes. More often than not, a bed.

50% of the population legally formalise those living arrangements, via marriage or civil partnership. A proportion that is steadily declining with each passing year. Which is interesting.

Yet 42% of marriages end in divorce. The median marriage duration ending in divorce was 12 years long.

Put those headline figures together and they paint a very intriguing picture.

If only half the population gets married, and just over half of those remain that way, then from a legal perspective the majority of us will leave this life as we began it: alone.

For brevity, the chart above uses the term “married” as a catchall for marriage and civil partnerships.

How does this information potentially inform our plans?

Under a “hope for the best but prepare for the worst” operating model, these living arrangement statistics tell us it is unlikely we will always enjoy the benefits of cohabiting with a significant other. Travel buddy. Partner in crime. Lover. Dining companion. Somebody to talk to and hang out with.

Divorce or a partner’s death has the potential to derail our best-laid life plans. However, life goes on. After an adjustment period, most people adapt. Indeed, many (but not all) widowers I know appeared to thrive once they had adapted to their new circumstances.

Financially speaking, such an adjustment may result in income potentially reducing via the loss of a salary or part/all of a pension, at the exact time when outgoings may increase significantly as all those household costs are no longer shared between two people.

An uncomfortable thought. One that receives little attention within Personal Finance circles.

But what are the odds?

Anecdotally speaking, it appears to be pretty common. All but one of my elderly neighbours are widowers. So too are my mother, mother-in-law, and a sizeable portion of their social circles.

Almost half of my former work colleagues have been divorced at some stage. In time, most subsequently coupled off again. Many of those opting for a less formal, and easier to exit, cohabitation arrangement the next time around. The financial interests of their new partner sometimes addressed in a legal will.

While anecdotes aren’t the same as evidence, I suspect my observations aren’t atypical.

To explore the data, let’s perform some of that probability maths that my elder son was using earlier, to figure out the statistical likelihood of a marriage surviving for a given number of years.

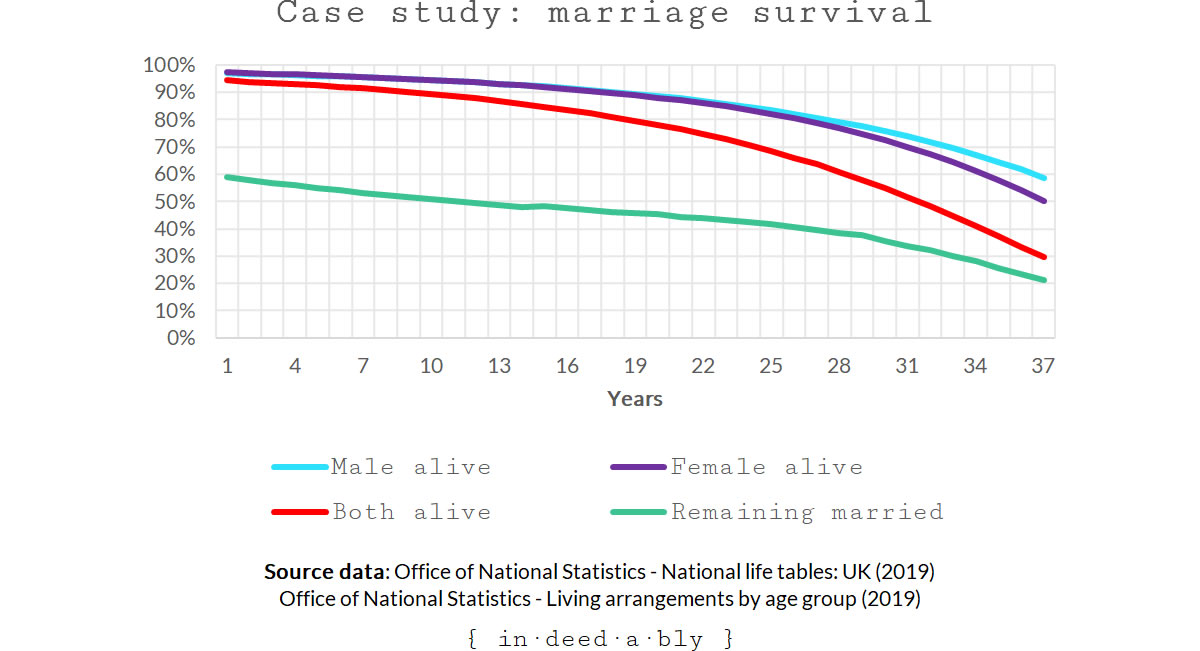

The final chart plots the individual projected life expectancy arcs for each of my lady wife and myself, starting at our current ages. The red line displays the probability of us both remaining alive. Finally, the green line applies the marriage survival rate to that combined probability, starting at the elapsed duration of our marriage.

The odds of a couple matching our demographic profile celebrating an anniversary together in 10 years time? 50/50. A coin toss.

There is a 1 in 4 chance that couple may throw an anniversary party 35 years from now.

Those near-term odds look daunting.

The longer-term marriage survival prospects were strangely heartening.

There is a non-trivial possibility of achieving those happy path outcomes. Yet looking at the odds, I wouldn’t bet my house on either occurring. The statistics suggesting an ever-increasing likelihood that they may not.

Catastrophising

If you are anything like me, you have probably imagined a future growing old and grey together with a significant other. Happily ever after.

A continuation of current living arrangements. Default choices, along the happy path.

What you may not have given much thought to is what the future might look like, if things change?

In some cases, insurance may help absorb the financial shock. Income protection, permanent disability, or term life cover are all examples where financial products (when used appropriately) may reduce a catastrophe to a more manageable financial inconvenience.

Buying time and breathing room to adjust to an unexpected new reality as a carer or living alone.

Perhaps you let your life insurance lapse once you had paid off the mortgage? Or maybe insurance coverage was an employee benefit of a job you once held, but have subsequently retired from?

The potential loss of an income or pension may mean no longer being able to afford the running costs of your current home. Heating. Maintenance. Property taxes. Utilities. They all add up. Homeowners can usually sell or downsize. Tenants have fewer options and face a less certain outlook.

Another scenario may be an irreconcilable difference, resulting in you no longer residing within your former home. Needing to start over. Furnish and equip alternative accommodations from scratch. An expensive undertaking that is unlikely to have been budgeted for.

If the majority of your net worth consists of equity trapped in your former home and age-restricted pensions, which you may not be old enough to access, then you would face a challenging road ahead. Asset rich, but cash poor.

Perhaps spousal support arrangements carve out a material chunk of your salary or pension income? A former partner, savvy enough not to remarry, has the potential to become a lifelong financial anchor. Indeed, financial advisors may encourage those receiving spousal support to take out life insurance on their former partner, to ensure they keep on paying from beyond the grave.

We naturally assume these things only happen to other people. Hopefully, that proves to be true.

Few of us spare much thought for these less than desirable outcomes. Until they happen to us.

Those who pursue financial independence devote a lot of time to pondering sequence of return risks. Calculating which asset drawdown rate will get them closest to possessing a photo album full of happy memories and an empty wallet by the time they reside in a coffin.

Blissfully unaware that there is a 1 in 3 chance their lifespan will exceed the 30 year retirement period that such calculations are typically based upon.

Ignoring the non-trivial chance their living arrangements may experience a significant upheaval long before then. Possibly more than once.

We all briefly detour down the unhappy path from time to time. An uncomfortable reality of real life.

Delving into these statistics has illustrated such outcomes are far more common than we care to admit.

An uncomfortable thought. Yet at these odds, one that shouldn’t be quickly dismissed as interesting yet irrelevant.

References

- Castellon, C. (2005), ‘Ever Heard of a Prillionaire?‘

- Gohd, C. (2020), ‘Astronomers reevaluate the age of the universe’, Space

- Lewis, R. (2020), ‘How Many Eggs Are Women Born With? And Other Questions About Egg Supply’, healthline

- Office of National Statistics (2015), ‘How has life expectancy changed over time?‘

- Office of National Statistics (2020), ‘Datasets: Divorces in England and Wales: 2019‘

- Office of National Statistics (2020), ‘Divorces in England and Wales: 2019‘

- Office of National Statistics (2020), ‘National life tables – life expectancy in the UK: 2017 to 2019‘

- Office of National Statistics (2020), ‘National life tables: UK‘

- Pagano, T. (2020), ‘Sperm FAQ’, Web MD

steveark 26 May 2021

I take comfort that the divorce rates for marriages in which one of the partners is a chemical engineer is under 8%. It is much higher in most other professions. In our case we will have been married 43 years tomorrow.

{in·deed·a·bly} 26 May 2021 — Post author

Congratulations to you both, that is a remarkable achievement. I hope there will be many more to come.

I wonder what age/duration our instinctive reaction to anniversary dates shifts from happiness to admiration? Applauding longevity the same way we celebrate achievement, which in the case of marriage it certainly is!

Isn’t it interesting how we continue to identify ourselves with a former profession long after we have moved on? Today you are an active tennis player, reluctant jogger, occasional waterfall chaser, volunteer, husband, and parent to a small tribe of successful adult children. Yet you think of yourself as a chemical engineer first, something you may not have done in anger for years (managers often manage rather than do directly themselves, your mileage may vary). I am similar, deep down I still think of myself as the Accountant I qualified as, even though I haven’t worked as one for more than 20 years!

Thanks Steveark, for sparking some fascinating questions to think about!

David Andrews 26 May 2021

I freely confess that my domestic situation is atypical. Having met later in life, my now partner and I already had separate finances and a property each. We still retain largely separate finances but we also now jointly own (tenants in common) a family home. We each have retained our former properties or as I call mine “the emergency house / bug out location”

As such, many of the potential disasters you have mentioned are already accommodated in our financial plans. Each of us would be able to financially survive without the input of the other.

I’ve witnessed other households for whom a domestic breakdown has proved emotionally and financially catastrophic. Where we live is mostly beyond the financial limits of a single person, let alone one who has to juggle childcare costs or reduced working hours.

“Hope for the best but prepare for the worst” – absolutely agree.

I’m a realist and as such I fully understand that over time people and their needs can change.

{in·deed·a·bly} 26 May 2021 — Post author

Thanks David. Sounds like you’ve landed on an arrangement that works well for you both, best of both worlds.

David Andrews 27 May 2021

It remains far from ideal in many areas but at least I know that many of the potential calamity scenarios are immediately survivable.

John Smith 26 May 2021

I have been married for 30+ years. Finances were put in common from the beginning because we started with zero net worth (no house, no savings, just our jobs < 500 euro/month). We even raised a child. Because we experimented minimalism, we are not afraid of divorce. Almost of my life I lived in less than 50 m2 house equivalents. So 100K in gilts (2000 euro/m2 x 50 m2) for a new location in a low cost of living will do it for a new “home”, worst case scenario.

FI is about happiness not grabbing things and then worry to not lose them. Let not forget that today a couple lives better than the kings in the past. And west / rich countries are spoiled (empires were built by blood and slavery, in the past; now by financial repression and “printing” fiat money from vid).

To increase the odds of longer marriage, two tips: say “yes daring” more often to her in private, and “it is as she said” in public, even if you did not believe it in full or all the time.

{in·deed·a·bly} 26 May 2021 — Post author

Congratulations on 30 years of marriage, John Smith.

Thanks for sharing your hard-won thoughts on matrimonial harmony.

Malcolm 26 May 2021

So personal

We had /have all our money in joint accounts where possible from when we got married

I run Quicken with a home page that has all our financial assets displayed

Each of us enters our spending once a week so where we are financially positioned is obvious to both partners at all times-no money debates-that’s what we have and that’s it!

xxd09

{in·deed·a·bly} 26 May 2021 — Post author

Sounds like a good arrangement, Malcolm.

Amazing how visible scarcity can focus the mind and help with decision making!

weenie 1 June 2021

Both my grandmothers were widows – one lived til she was 94, but sadly, ravaged with dementia, she did not know anyone in the last few years of her life. The other matriarch is still going at 95, her body failing but her mind still sharp as nails. Perhaps my genes suggest I’ll make it to my mid-90s. Arguably, I’ve eaten better but I’ve also led a pretty sedentary life compared to them, plus the years of abusing my body with alcohol on nights out might not help with longevity!

On the marriage front, 3 divorces in my family and two of my closest friends are divorced too. Research suggests that the happiest people are unmarried, childless women.

Guess I’m on the path to being as happy as I can be!

{in·deed·a·bly} 1 June 2021 — Post author

Thanks weenie, wow 2x the mid-nineties suggests you’ve got a great chance of having won the genetic lottery!