On a bitterly cold day, five-year-old me shuffled my gumboots through a pile of fallen leaves half as tall as I was. Amidst the kaleidoscope of autumn colours, I spied a yellow banknote.

Paper. A bit soggy. Featuring the portrait of a smiling old man wearing glasses and a dodgy bow tie. Prominently displaying the number 50 in the corner.

I picked it up, and with much excitement stumbled after my father striding down the footpath.

He slowed as I called out, and his eyes lit up when he saw the banknote I waved in my icy fingers.

“Wow! Where did you get that?” he asked, as he extracted his wallet from his back pocket.

“Tell you what, why don’t you give me that wet yellow one? I’ll give you two dry banknotes in exchange. Two is better than one, right? A nice green one, and this brown one with pictures of kangaroos on it!”

I suspiciously eyed the two pieces of paper he proffered.

The green note featured the picture of a sheep and had the number 2 in the corner.

The brown one did indeed show a mob of kangaroos below the number 1.

I tentatively exchanged my $50 note for the $3 my father waved in front of my face.

After I had carefully examined them both, my father plucked them from my five-year-old fingers and popped them back into his wallet for “safekeeping”.

On the way home, my father decided we should celebrate. Having no comprehension of price or value, my five-year-old mind fantasised about eating Freddo Frogs while playing with some new Lego.

Alas, life is full of false promises. Self-delusions. Wishful thinking.

My $3 purchased a cask of cheap supermarket wine for my father, and earned me a loud ringing sensation in my ear when I protested about the unfairness of that outcome.

The stories we tell

This week I’ve invested a bunch of time, consuming over 1,300 pieces of Personal Finance content.

Nearly every article, post, story, or video produced in the last 90 days. By nearly every English language blogger based in Australia, New Zealand, Europe, and the United Kingdom.

I’ve learned a little.

Been entertained a lot.

Discovered some great new (to me) voices.

Mentally associated podcasts with talkback radio, a linkage that once made cannot be unseen.

Recognised a delicious irony. My attention span is too short for YouTube! I can comfortably skim a dense 1,500 word article, or the transcript of an hour-long interview, in less time than it takes to sit through a low calibre listicle video full of advertising and self-promotion.

I was saddened to learn of the death of a creator I regularly read a few years ago. The demise of several once great blogs. An alarming number of long-dormant blogs idling in the departure lounge.

This exercise reminded me that there is a lifecycle to content creation.

Starting with a burst of creative enthusiasm. Full of ideas.

After a while posting frequency falls away. Competing priorities and waning interest conspiring to lure the creator onto other things.

For a time, their creative outlet remains as a monument to a passing fancy. Tumbleweeds rolling through abandoned social media accounts, serenaded by the sound of crickets.

Eventually, the hosting contract may expire, rendering the endeavour a distant memory. A ghost in the Wayback Machine.

The exercise also reminded me that each creator is part of the way through a unique journey. Doing things their own way. Learning at their own pace. Following their own interests. The “personal” part of Personal Finance.

Much of the content was good. Entertaining yarns. Teaching a lesson or two. Sometimes both.

Some of it was bad. Errant. Foolish. Misguided. Wrong. Strongly held opinions not grounded in fact.

A minority were downright deceitful, bordering on fraudulent. Selling impossible dreams to a self-selecting audience of perceived easy marks. An audience seeking to improve their finances, but lacking the knowledge required to spot the charlatans, sharks, and shysters who prey upon them.

Reality check

That day long ago, my simplistic fantasies met with a harsh reality check.

Reflecting back on it now, from the safe distance of some 40 years, I learned several things from the experience.

Expected outcomes can be overly optimistic.

Fairness and justice are the stuff of fairy tales.

Predictions for the future should take into account predictable externalities.

That challenging my father was best done while wearing a helmet and with a running start!

Looking through all those pieces of Personal Finance content, I frequently witnessed a pattern of wishful thinking and oversimplification.

Many Personal Finance bloggers eventually write a “power of compound interest” post at some point. A simple chart demonstrating a snowball effect. The misattributed Einstein quote. Perhaps a neat table illustrating that compounding and patience are all that is required to become a millionaire.

Which is fine, as far as it goes.

The sort of simplistic example we might expect to see in a high school maths textbook, teaching children how to perform compound interest calculations.

Except here is the thing. These explanations present a rose-coloured view of a predicted financial outcome. A feat that is technically possible, yet the chances of an investor’s performance actually achieving that outcome are vanishingly small. Like successfully timing the market. Or predicting which fund manager might outperform the index over each of the next three years.

To illustrate, let’s pretend my long lost $50 banknote had been deposited in my bank account, rather than pilfered by my father.

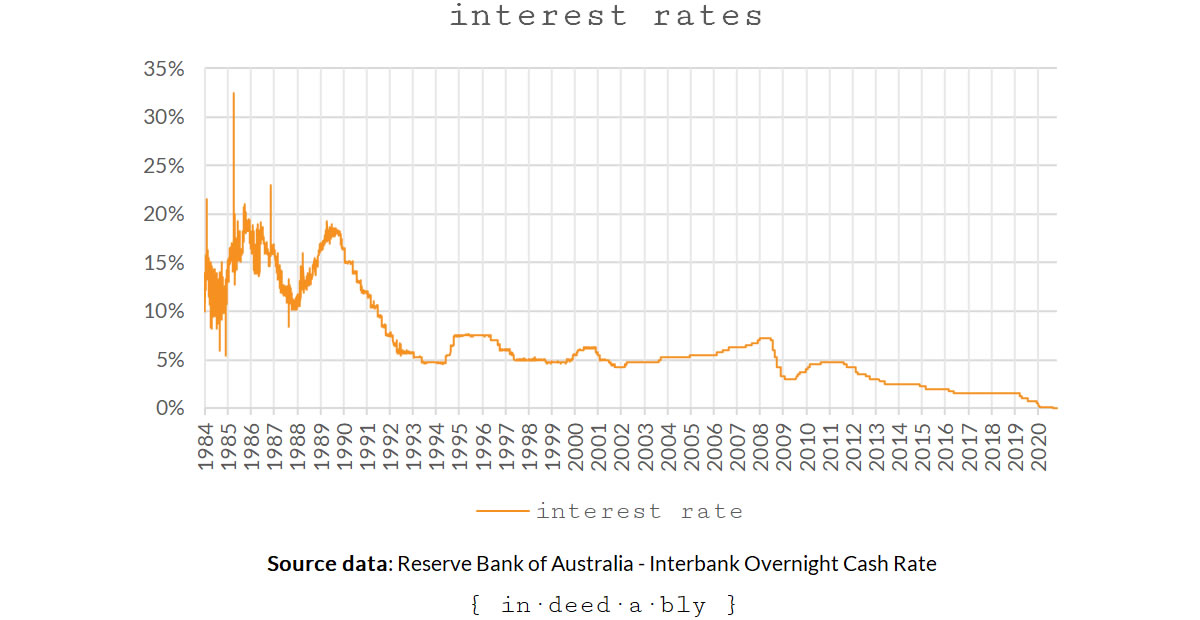

Back then, the official interest rate was 12%, but as we all know, interest rates vary over time.

I used the overnight interbank rate as a rough proxy for interest rate my bank account might have received. Rates climbed to over 30%, before falling back down to the near 0% rates we see today. The average rate throughout that period was 6.45%, yet in the real world there was none of those nice smooth constant and predictable linear progressions seen in the textbooks.

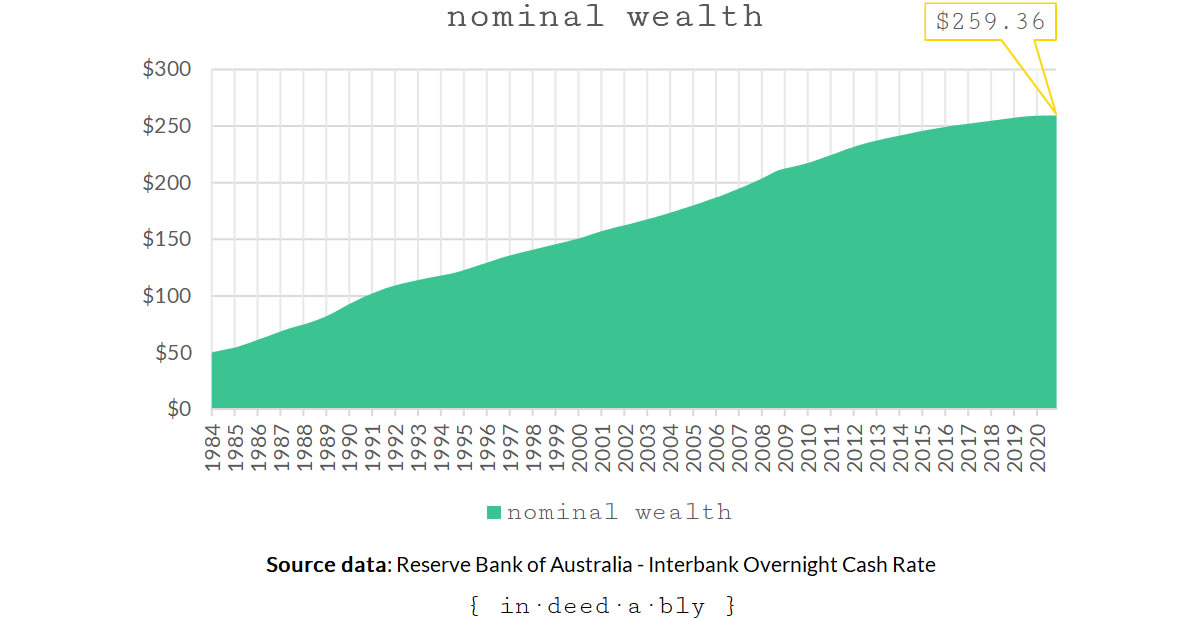

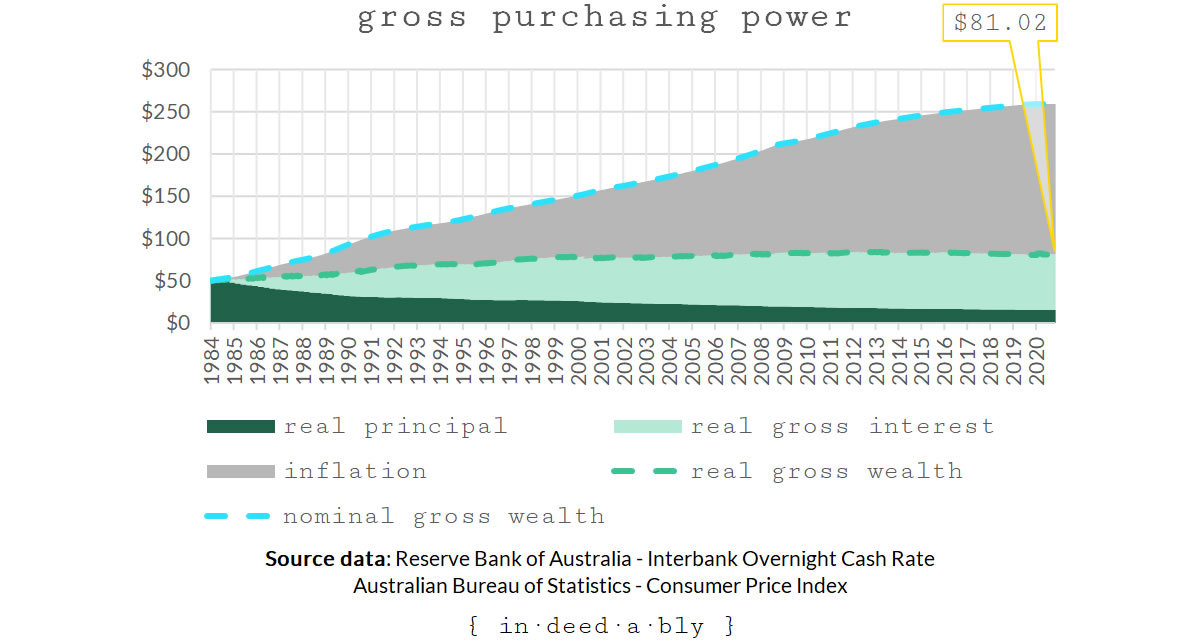

Next, I applied those rates to a starting balance of $50 which resulted in a familiar “power of compounding” chart, though my curve is perhaps a bit lumpier than most. Today, that $50 would have grown to $259, a 5x investment outcome. That is an annualised rate of return of 4.55%. Hurrah!

Before we break into the victory dance, let’s consider what that actually means.

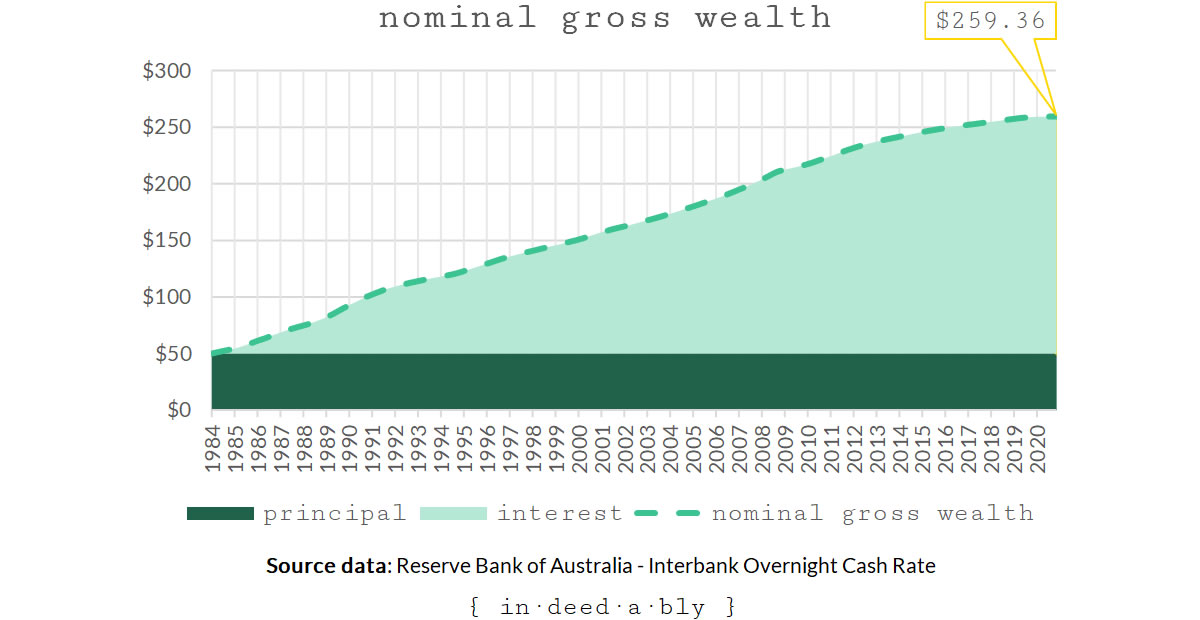

The next chart illustrates a breakdown of that investment, separating the capital we originally invested from the compounding interest we might have expected to receive. This is important, as conflating capital contributions with investment returns is a common way investors deceive themselves.

Taxation

The investment performance so far seems good, if not exceptional.

Except in the real world we often need to pay tax on our investment income. How much tax, and when it is due, may vary by a multitude of factors. Age. Jurisdiction. Martial status. Personal circumstances. Private rulings. Tax-advantaged status of the account. And many more.

Unsurprisingly, many folks take one look at this complexity and decide to pretend it doesn’t exist.

Income generated within a fully tax-exempt investment account, such as an ISA in the United Kingdom, may genuinely resemble the simple compound earnings curve.

However, the reality is that much of our investment income will most likely incur some degree of taxation.

Generally speaking, the jurisdiction where I grew up taxed all forms of income (apart from capital gains) at the same marginal tax rates. Investment income got added to “earned” income, meaning it was taxed at the individual’s highest applicable tax bracket.

To illustrate the potential effect taxation may have on investment returns, I performed a quick piece of digital archaeology to track down the top marginal income tax rates that had been applicable each tax year throughout the period.

Like interest rates, these frequently change, ranging from 60% when I was a kid, to 45% today.

Taxes were calculated on a per tax year basis and paid in arrears.

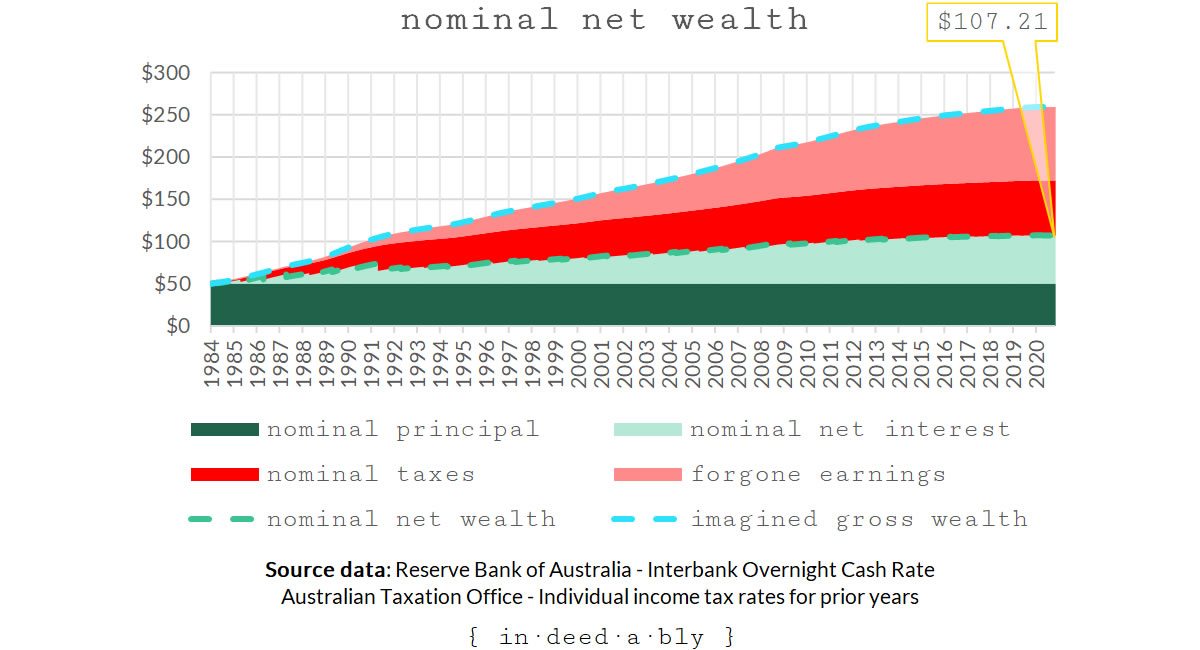

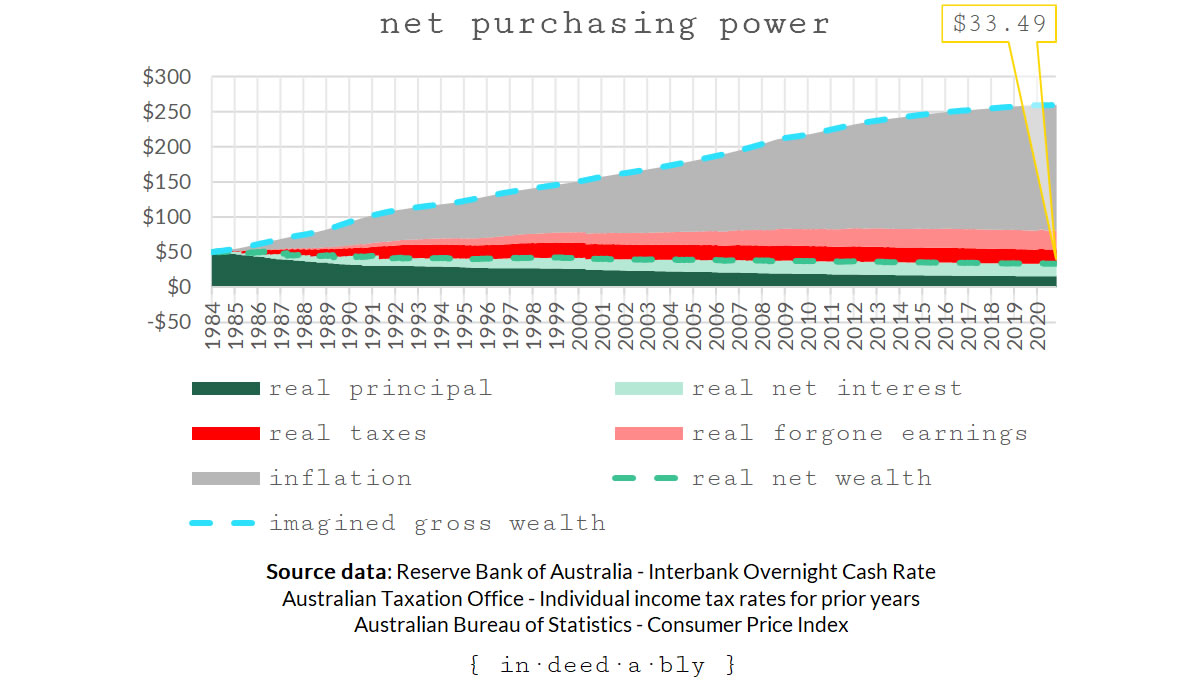

Notice the huge impact taxes can have on our investment returns! The total value of the investment at the end of the period has fallen from the $259 above to $107. Our investment return is now just 2x, an annualised rate of return of just over 2%.

There are two aspects to the hit we take from tax. First is the tax itself, monies we have to pay to the government, as shown by the red segment on the chart above. Second, is the forgone investment returns, shown in pink above.

Compounding cuts both ways, boosting returns when we leave monies invested, while increasing the opportunity cost associated with money spent.

The investment returns achieved by most people would likely fall somewhere between these two ends of the spectrum, bounded by the simple and optimistic example and this worst-case fully taxable example.

Inflation

Another common thing folks naïvely choose to ignore is the impact of inflation on their purchasing power over time.

That $50 from when I was a five-year-old has the purchasing power of just $15.62 today.

Isolating the impact of inflation produces a chart like the following.

After compounding for ~40 years, my $50 initial investment will have grown to have a real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) purchasing power of $81 today. That represents a real return of 1.62x, and an annualised real rate of return of 1.3%.

The grey segment highlights just how much of those “magic of compound interest” charts actually consists of inflation. Our money has to work hard just to maintain purchasing power, let alone grow!

Now let’s illustrate what the combined effect of inflation and taxation would have had on my returns. It does not make for attractive reading.

After ~40 years of compounding, and accounting for tax, the purchasing power of my inflation-adjusted investment would today be just $33.49 had I been a high income earner in the top tax bracket. In other words, worth less than I started with. My annualised real rate of return would have been -1.1%.

This was a predictable outcome, as the interest rates offered on everyday current accounts tends to be lower than the inflation rate. It highlights why cash is generally not a fantastic investment, as inflation erodes its purchasing power over time.

Reasonable expectations

Hopefully, this simple illustration highlights the importance of having realistic expectations when we are planning our personal finances.

It would be a nasty surprise indeed to have expected $50 to grow to a purchasing power equivalent of $259, only to discover it had actually fallen in value after accounting for predictable externalities such as fees, taxes, and inflation!

Compounding is a powerful tool in our financial toolbox. However, if we fail to minimise the fees and taxes that we incur, the effectiveness of that compounding will be greatly diminished.

We should ensure that our own ignorance, laziness, or incurable optimism does not blind us or oversimplify our financial forecasts and projections. Adopting an evidence-based approach to our financial planning provides a means of crafting a vision of the future that is both realistic and grounded in fact.

Simplistic high school maths textbook examples might illustrate a basic concept, but if we are not careful they can paint an unrealistic picture of the likely outcomes we might reasonably expect to achieve.

Five-year-old me thought I was rich when I found that banknote amongst the fallen leaves, but my dreams of amazing rewards were sabotaged by my poor planning and unrealistic expectations.

Hopefully our readers never experience a similar disappointment, should they base their financial projections upon simplistic examples they happened to find on a Personal Finance blog.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020), ‘Consumer Price Index – Australia‘

- Australian Taxation Office (2020), ‘Individual income tax rates for prior years‘

- Reserve Bank of Australia (2021), ‘Interest Rates and Yields – Money Market – Daily – 1976 to 31 December 2010 – F1‘

- Reserve Bank of Australia (2021), ‘Cash Target Rate‘

- Sovereign Quest (2021)

Jono 12 January 2021

“A ghost in the Wayback Machine” – excellent work 🙂

{in·deed·a·bly} 12 January 2021 — Post author

Thanks Jono, glad you enjoyed it.

Pendle Witch 12 January 2021

“martial status”? I know marriage can be combative but that’s very pessimistic 😉

Thanks for the clear run through of the stats. The moral of the story is: don’t pick up money off the ground because 40 years later it will likely have a negative impact on your net wealth! (*if you become a high-rate taxpayer)

{in·deed·a·bly} 12 January 2021 — Post author

Lol, thanks Pendle Witch. I would like to commend your enthusiastic interpretation of the subject matter presented. Your answers, while almost exactly wrong, show a remarkable consistency and demonstrate an applied application of the survival skills necessary to survive in this post-truth world (such as choosing your own facts and embracing alternative narratives). ?

Governments have long bribed and induced their citizenry into marriage. If it weren’t for the tax breaks and visa access, who in their right mind would ever willingly enter into such a diabolical legal arrangement as an open-ended unlimited liability general partnership!?

An alternative moral may be to avoid taking advice from any armchair expert that cites Einstein as some form of financial guru. According to the internet, his first wife cleaned him out in their divorce, including laying claim to any future Nobel prize winnings!

Fire And Wide 12 January 2021

So good to see a well-worked example of taking the complete picture into account, not just the happy story compound interest graphs. It makes a big difference and you are right, so many people seem to skip this trickier part.

Real returns are obviously what actually matter – I always thought it would be great if investment products had to advertise these alongside the overall rate. Who wants to invest at -2% then….anyone, anyone…?!?

One thing I’ve never understood is why capital gains tax makes no allowance for inflation now. You sell something you’ve held for a while, be it second properties, shares, whatever. You get to pay tax on the inflation growth just the same as any actual returns. Hell, even if you’ve actually lost money in real terms you’ll pay tax if it’s not more than inflation. Oh, so I do get it then 😉

Going through over 1,300 posts is nothing short of heroic. Hats off to you – and thanks from all of us for doing so. The new site is awesome.

{in·deed·a·bly} 12 January 2021 — Post author

Thanks Fire And Wide.

Where I grew up, the cost base of an investment was indexed before any capital gain calculation was performed to avoid that very problem. Indexed gains were then added to earned income and taxed at the relevant marginal rates just like any other form of investment income.

That arrangement worked pretty well for a long time, before a vote buying government halved the rate of capital gains tax owed providing the investor had held their investment for more than a year.

Eventually, they did away with the indexing component, but the 50% “discount” for holding an investment for more than a year remains to this day.

That’s very kind.

While putting together Sovereign Quest, I ended up stumbling across 250+ different creators. To figure out what form of presentation would be most effective and useful, I needed to understand who those creators were? What sort of content they produced? Publishing cadence? And so on.

It was also important to be able to screen out those creators focused on exploiting their audiences, rather than seeking to help, educate, or simply entertain them.

weenie 12 January 2021

“My attention span is too short for YouTube!”

This! I’d much rather read the transcript!

Even blogs which have been going for years will regurgitate the compounding post, although I can’t say I’ve ever done it (I don’t think so, although I may have menioned the ‘snowball effect’) – starting so late, time isn’t on my side so I’ve largedly missed the compounding boat!

Anyway, I applaud your efforts trawing through 1,300 posts and thank you for picking out the good stuff for us to read.

{in·deed·a·bly} 12 January 2021 — Post author

Thanks weenie.

It turns out voice is a very inefficient means of effectively communicating information. Hardly an Earth-shattering revelation, but it was jarringly apparently when compared to all the reading I was doing.

Voice can be friendly, engaging, even funny… but always slow. We can compensate a little by cranking up the playback speed until the speakers sound chipmunk-esque, but pretty quickly our ability to comfortably absorb and digest the information falls away.

My conclusion was podcasts are ok as background noise, while we are focussed on doing something else like driving or exercising. However, our knowledge retention ends up being pretty poor because we aren’t really focussing on retaining the detail of what the speakers are telling us. Hence the drive-time radio reference, lots of noise but very little signal.

The other problem is we are quite good at remembering pointers to information, allowing us to skim back to (or search for) the salient points in text, even being able to find again something we read weeks or months ago. Trying to skip through a video or podcast by contrast is hit and miss, and with audio search being so poor it becomes like trying to find a needle in a haystack.

So voice becomes a good medium for interviews, where the purpose is more about conveying a sense of the speaker’s personality and sense of humour, but terrible for to sort of informative fact based content most Personal Finance creators generally produce. There are some rare exceptions of course, but listen to any competent Personal Finance author doing the podcast circuit plugging their latest book, and you will quickly see what I mean.

cat793 16 January 2021

I have discovered this for myself recently. I drive for a living and am tired of listening to music so decided to give audio books a try. I enjoy listening to them but find I don’t retain much information because I cannot organically pause, reflect and let my mind play over interesting points as I can when I read the book. I think this process aids memory formation and comprehension which I miss out on when listening.

{in·deed·a·bly} 16 January 2021 — Post author

Thanks cat793.

Another aspect of audiobooks is the upfront knowledge of the time commitment involved. I hadn’t realised that many audiobooks are abridged versions. For example the audible version of “The Intelligent Investor“, with the same cover as the paper book copy I have, has a runtime of 2h 44m. Dig a little deeper and the unabridged audio version has a runtime of 17h 48m.

Either Benjamin Graham was a very wordy writer, or the editors of the former recording decided to chop 84% of the text in the interests of expediency!

Were we to read (rather than skim) the paper based book, it would take us more than a few hours to work through the dense text, but probably less than 17 hours in total. Few of use have the attention span required to attentively listen for more than an hour or a two at a time before we glaze over and switch off.

Another common favourite in the Personal Finance space is “Rich Dad Poor Dad“. Runtime for the audio book is 6h 9m. Most of us could read it in a single sitting, and comfortably summarise the important bits in a t-shirt slogan.

FIRE v London 13 January 2021

Good post – on two levels – thank you! I am totally with you regarding much preferring reading to watching. Our age, perhaps? Or my education forcing me to assimilate education too fast….

The important implication of your ‘simplistic’ analysis is how valuable tax-sheltered accounts are, as you touch on. Here the UK scores particularly highly, thanks to ISA tax breaks being unlimited, as well as fairly typical (vs other countries) pension tax breaks. Oz’s tax-free pension payments (as I understand it) are unusual but feel much less interesting for those of us seeking early financial independence. In the current environment, with interest rates minimal, inflation very low, but equity returns of 7%+ a year, if you can get these returns in a tax-free way you really can double your purchasing power versus cash every ~10 years with equity investments, I feel fairly confident. Us FIRE-minded Brits must give continual thanks for our tax breaks.

{in·deed·a·bly} 13 January 2021 — Post author

Thanks FvL.

I’m not sure it is an age thing. My kids are both back doing home schooling. They rave about the asynchronous “submit the work by end of the day” classes and complains mightily about the inefficiency of the synchronous Zoom style lessons taught lessons.

That said, my elder son’s native habitat is YouTube and WhatsApp (though his gamer friends mostly seem to be migrating to Signal after the recent watering down of WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption). When I asked him about it, he said he likes the human element of the spoken word when the goal isn’t to learn something specific. Makes him feel more connected/less alone while he’s idling instead of working or learning.

You’re absolutely right about the cumulative benefits of availing ourselves of tax-advantaged accounts.

This will probably be an unpopular opinion, but much as I enjoy the tax benefits while they are available, personally I would prefer to see all income/realised gains taxed at the same rates and without the loopholes/shelters. The existing tax take could then be achieved at lower tax rates for everyone.

The disincentive this would create to save for retirement could be partially offset by borrowing another aspect of the Australian system, making contributions mandatory (i.e. no ability to opt out). If non-compliance becomes and offence, there is then no need to incentivise participation via tax breaks.

FIRE v London 13 January 2021

You are right that with mandatory pension saving tax breaks for savings would be hard to justify. However we have quite an aversion in this country (our Saxon roots, one of my older friends calls it) to making things mandatory. Voting, pension contributions, and keeping cats indoors at night all included. Even driving within the speed limit, one could argue!

The Australian level of compulsion is very high too. I prefer our policy here – opt outs possible but very rare, 8% contribution is a very sensible level, pension income taxable as per any other income. Things I would tweak are relief for high earners, and our language/debate about risk – framing cash as ‘no risk’ and equity investment as risky feels downright inverted when it comes to how you should be guiding graduates into the pension preparation jungle, and the 8% level only works if you have people investing early in equities.

{in·deed·a·bly} 13 January 2021 — Post author

Your framing point is well made FvL. The real risk is in not investing!

The high mandatory contribution levels are partially offset by additional flexibility, such as being able to purchase property and take on debt within the age-restricted pension wrapper.

The Australians don’t have everything right though, for example tax loopholes that encourage people towards the complexity of self-managed super funds with corporate trustees, or establishing discretionary trusts to avoid tax.

Given the typically low voter turn out, piss poor adherence to pandemic “guidance“, and prevalence for speeding on motorways I think making things mandatory (and enforced) a bit more often in Britain wouldn’t be a bad thing. Brexit was a good example, where 28% of eligible voters didn’t bother to vote, and if they had the outcome would have been very different.

Carolyn Gowen 15 January 2021

Another great piece sir, and good to see someone cover this topic as comprehensively as you have.

Ah, I still recall the heady days when indexation was applied to capital gains. When that enormous tome ‘Stubbs’ was frequently called upon for 31/03/82 share prices and for the requisite details on share issues needed to calculate the CGT position.

In my experience, inflation is the item most likely to be overlooked and not just in terms of general price inflation. We all have our own personal inflation rate that applies to our spending and the wealthier one is the more likely we are to spend our cash on services rather than goods (that said, this probably doesn’t apply so much to the FIRE community), the costs of which tend to rise at a faster rate than goods (think little Johnny’s private school fees, private medical insurance etc). So inflating your spending at a rate slightly higher than your assumption for general price inflation can make sense and it can be quite sobering to see what a difference just 0.5% a year makes when you’re looking at a 50+ year time frame.

I also found your comments on reading vs the spoken word interesting as I dipped my toe, as TFB, into the world of YouTube last year. I’ve not recorded as many pieces as I would have liked, for a number of reasons, but it’s been interesting to see how the pieces which are personal have got far more views than the ones based on the job I do. It seems that videos featuring donkeys are way more interesting than those looking at how to find a financial planner ?

{in·deed·a·bly} 15 January 2021 — Post author

Thanks Carolyn.

Your observation about the creeping increase in costs of services is well made. The automated annual rise in insurance premiums is a great example, insurers count on the fact most people will be too lazy or distracted to bother shopping around for a better deal, so their once competitive quote inflates over time until it becomes so bloated the policy holder is driven to take action.

On the spoken word point, there are some exceptions. Pete Matthew does a great job with his Meaningful Money podcast, providing an accessible introduction to often dense and impenetrable topics, in a similar way to those “Idiot’s guide” books used to for computer programming back when I was starting out. That said, the YouTube videos of Pete glazing over or wandering around his office while some self promoting guest jibber jabbers about their latest book are comedy gold!

LukeM 17 January 2021

I do come close to screaming every time I see more ‘compound interest’ waffle. Yes, you can calculate a compound annual growth rate from a start value and an end value, and draw an alluring exponential curve – but it isn’t how real-life investing works!

{in·deed·a·bly} 18 January 2021 — Post author

Thanks LukeM.

I think compounding is one of those things bloggers tend to discover very early on in their investing journey, and it often blows their mind.

The use cases are relatable and often dramatic. Being able to shave years off a mortgage term. Seeing a potential retirement date moving forward by a year or two, with little more effort than moving closer to the back of the plane when taking holidays. Etc.

What keeps me sane each time I skim through a post rehashing a standard personal finance trope is the knowledge that while it may be old news to you and me, the blogger might be encountering it for the first time. Indeed, half the stuff I write about here probably generates the same frustration amongst those already further along their own journeys than I am!

Q-FI 18 January 2021

With all of your recent blog reading/research, you make me feel pretty lazy that I struggle to keep up with the only handful of blogs I like to read. Haha. Sounds like you’ve been busy and enjoying your project thus far. Pretty cool.

I’ve always found people tend to underestimate the tax game. For me personally, I think it’s one of the biggest determinants to long term wealth, how well you play it. But that’s just me.

I agree on your assessment of the natural blog lifetime progression. I’ve also seen that play out in my relatively short time of reading. I still enjoy writing, but will that be for another, 6 months, a year, 5 years? Who knows. I’ll keep it up until life gets in the way like it always does.

{in·deed·a·bly} 18 January 2021 — Post author

Thanks Q-FI.

You’ve got the right approach, choose a few voices that resonate and follow along their journey for a time. It should be fun, not a chore. What Sovereign Quest is attempting to do is make it easier for readers to discover those voices that appeal.

Absolutely on the tax point. Once a person is earning more than a little, tax becomes their second highest expense category after housing. For higher earners, without proper planning it may soon become their highest expense category!

Ben 23 January 2021

Accumulated life experience is teaching me that inflation is a strange beast.

If suffers from the common problems of financial (in fact, all) metrics: seeking to represent a diverse reality with a single value that has the illusion of precision.

This becomes clear when I read Victorian novels and attempt to compute “today” amounts using the Bank of England’s inflation tool. Or try to find out if Lego kits and computer games are more or less expensive than when I was a boy.

Over my adult life official inflation has been edging down to 0%. But certain things are unaffordable: housing, social care, private schooling.

20 years ago in the U.K. we could receive 5 TV channels for the cost of a TV, a TV licence and an aerial. Now we can receive infinite content, but the cost stack includes fibre broadband, decent mesh WiFi, iDevices or dongles, and subscriptions to multiple streaming services. As well as the TV licence.

So inflation is low, unless you are buying a house, in which case it’s been rising at 6-10%/year. Chinese goods mean computers are cheap, unless you choose to subscribe to the whole stack to fully realise the potential.

With investing, the real power is putting your money into the assets that are rising in value (normally because of underlying supply and demand) while basing your spending on things that are falling in value (food, necessities, clothes). Performing this arbitration is a life’s work, and is often specific to individual circumstance (i.e. luck and opportunity). Concentrating on the general pattern, rather than the minutiae of specific asset classes, exchange rates, trading strategies or monetary policy, is the way to success and sanity.

{in·deed·a·bly} 23 January 2021 — Post author

Thanks Ben.

You raise an astute point that the rates of inflation on individual classes of product vary greatly. The real cost of travel, communication, electronic goods, furnishings, food, and financial services (the unmanaged/automated variety at least!) have plummeted in recent decades.

Benedict Evans wrote about a couple of dramatic examples recently:

By contrast, the real cost of many of the essential things like education, healthcare, nursery fees, aged care, and housing has skyrocketed.

My point with this post is to consider inflation (and fees and taxes), rather than simply pretending they don’t exist because they are complicated/hard/inconvenient.