“[REDACTED] Bank has noticed your [REDACTED] debit card ending [nnnn] was used on 11-06-2020 19:45:37, at [REDACTED] for £99.99. This payment was declined. If this was you please reply YES, otherwise please reply NO. There is no need to call us. Responding to this text is the quickest way to update your account.”

Interesting,

The alert appeared to be about one of my cards.

It was a newish one. Issued to replace its expired predecessor, the week before the lockdown began.

I had opened the envelope. Scrawled on the signature strip. Tested that the card worked at the automatic teller machine around the corner. Then stashed it in my “go bag”, where it remains today. I checked!

Both the accompanying letter and expired card had been ritually sacrificed to my crosscut shredder.

Neither the card nor the debit card number had ever been used in a store or to make purchases online. Its details had not been registered as a payment method for the likes of Amazon, ApplePay, or Paypal.

But here is the thing: it wasn’t me attempting to make the purchase!

I briefly wondered whether the text was a phishing scam?

What better way to dupe a punter into sharing their personal details and memorable information than to initiate a fake fraud alert and investigation?

I had received similarly worded text messages from the bank a couple of times in years past. They had originated from the same number. Previously, it had been me making a purchase. In each instance, the transaction had been inexplicably declined by the card payment processor, resulting in one of those awkward “computer says no” moments at the checkout.

Text message swiftly arriving to defuse the tension between shop assistant and hopeful customer.

A quick “YES” in response, and the transaction had successfully gone through on the second attempt.

Of course, that didn’t mean it that it wasn’t a scam this time.

A fraudster could have spoofed the originating phone number that the bank used for such messages. It isn’t hard to do. Was I being paranoid after my recent identity theft experience? Possibly.

Curious, I texted back “NO”.

Immediately I received another text message from the number.

“Thanks for confirming that it wasn’t you making the payment. We will call you as soon as we can between 08:00-21:00. Out of these hours please call us on [REDACTED]”

Then my phone began to ring.

Upon answering, I was warmly greeted by a friendly lady with a Scottish accent who claimed to be from the bank’s fraud detection department.

She asked a couple of questions in an attempt to verify my identity.

I responded by asking how I could verify hers?

I had received a cold call from a stranger.

Who was calling from an unfamiliar number.

They sought to confirm my address and memorable information.

To my simple mind, this was exactly the sort of thing a bank fraud prevention officer should be discouraging!

The lady conceded that I had a point. She provided me with a reference number, then told me to look up the contact number for the bank’s fraud line on its website. Then she hung up.

Which left me wondering how hard would it be for a bad actor to modify static content on a bank website? How long would it be before anyone noticed? How many customers would be suckered?

Definitely paranoid.

Five minutes later I had called the bank’s fraud number. Had my identity verified. Twice. Supplied the reference number. Now I was once more speaking to the friendly Scottish lady.

She asked whether I had made the purchase that had been declined?

I had not.

She asked whether I knew of anyone else who may have been making a purchase using my account? For example, children making in-game purchases on a computer game, or a spouse sharing an online shopping account with pre-populated payment details.

I did not.

I was pretty sure my kids had not figured out how to turn the Amazon man into Santa Claus. Yet.

Nor had they learned to avoid culinary “Dad-sasters” by ordering home delivery pizza on my account.

The fraud prevention officer checked the account transaction history, and conceded it probably wasn’t me making the purchase attempt.

The only transaction on file that had involved the debit card in question had been the ATM withdrawal, three months earlier.

She apologised for the inconvenience caused, but said the card appeared to have been compromised. It would need to be cancelled, and a replacement issued.

5 days business days without a debit card didn’t bother me overly.

The fact that the card had somehow been compromised troubled me greatly.

Had a burglar broken into my house undetected during lockdown? While we were all home. Found the card. Taken down the details. Attempted a purchase. But not stolen anything. Implausible.

Was the “burglar” one of my kids? My lady wife? The troublesome cat? Possible, but unlikely.

Perhaps the bank had a data leak, or their systems were compromised. It couldn’t be ruled out.

Could one of the staff at the local supermarket where the cashpoint was located have obtained my card details from their CCTV camera footage? Image resolution has come a long way in recent years. Who am I kidding?

Maybe an enterprising thief fitted a card skimmer to the ATM? Harvesting my details as I inserted the new card. It is not unheard of.

Once again the uncomfortable truth was I would likely never learn the answer.

Good intentions

For many years, my father recorded all his usernames and passwords in a little black diary that he carried everywhere he went in his shirt pocket. The key to his banking, brokerage, and tax kingdoms.

This approach had evolved after his house was burgled. Twice.

The first time thieves stole my father’s coin collection. My mother’s engagement and eternity rings. And all their electrical equipment, including computers.

The second time occurred roughly three months later. Shortly after the insurance company had delivered “new for old replacements” for the majority of the items taken in the original break-in. The police said this was a common pattern.

His children tried to persuade him to move to a more secure solution. Arguments ranged from single point of failure to the major inconvenience caused should his diary ever be lost. Stolen. Or wet.

We failed.

Each Christmas one of us would give him a replacement diary for the next calendar year. He would spend Boxing Day laboriously copying out all the details into the new edition. Our actions enabled his bad habits, but at least he had the old diary as a backup. “Just in case”.

All that changed years later, when we had the misguided idea to hold a surprise party for my father. Seeking to celebrate a milestone birthday or a major life achievement, surrounded by his friends and former colleagues. This was back in those innocent days when doing such things was considered nice, thoughtful even.

Today it would be an egregious and unforgivable violation of personal privacy!

One of us liberated the pocket diary while he was taking a nap, to look up the phone numbers of his best friends, so that we could enlist them as co-conspirators in organising the party. The diary was safely returned before he woke up.

The party was a success. My father had a great time, even tearing up a little while giving a nice speech thanking everyone for helping him celebrate whatever the occasion had been.

Upon learning that his security system had been breached, my father took immediate action. He enlisted the help of one of his friends to set up a password manager on his by then ancient laptop.

All those usernames and passwords were diligently keyed into the software vault, secured by a master password. One password to rule them all.

From that point onwards, password manager browser add-ons allowed anybody with access to my father’s computer to log into any of his online accounts at the click of a button.

He continued to maintain the pocket diary as an offline backup, now including the password to his password manager.

We only discovered after his death that my father had used the same password for his computer and password manager that he had been recycling for years on just about every online account he had ever opened! Choosing convenience over data protection until the very end.

pwned

My recent spate of identity theft issues suggests my approach has also been found wanting.

Had I become complacent or lazy?

Chosen convenience over data protection once too often?

Failed to keep abreast of the ever-changing best practices and cybersecurity threat landscape?

The truth is probably a mix of all three.

Purchasing items online follows a fairly standard series of steps, involving both “something you have” and “something you know”.

- Register for an account, typically with your email address.

- Create a password. The “something you know” part.

- Demonstrate you control the email address via responding to a confirmation link. The “something you have” part.

- Supplying a payment method and billing address details.

- The next time you visit, click the “forgot password” link because a material number of repeat customers won’t remember their password. A password reset link will be emailed out, providing an automated means of accessing the account without knowing the password.

The email account is key here. Serving as usernames for most accounts, and also the workflow for resetting a password. Controlling the email account grants control of many of the other accounts. A skeleton key to life.

Therefore it would make sense to reduce the risk of a bad actor gaining control of the email account.

A strong password, unique to the email account, is a practical first step.

Except a strong password is very difficult to remember. So you write it down somewhere.

You decide an electronic “somewhere” is preferable.

However, that “somewhere” then provides an additional vulnerability vector.

So you hide it behind another password. Perhaps inside an Excel file. Or within a password manager.

Being suspicious by nature, you don’t trust these password stores to remain secure from a determined attack . You choose to store only part each password within them. Creating another layer of “something you know” protection by requiring the addition of couple of characters that aren’t written down, before anyone could successfully make use of the content of the password register.

Then you remember that hard drives fail.

Thumb drives containing backups are small and easily lost.

Planned obsolescence means electronic goods like phones and computers get periodically replaced.

You decide to make an offsite backup of your password backup.

Synchronising the file using a cloud storage provider like Dropbox. Manually uploading it to a service like iCloud. Perhaps using your password manager’s native replication mechanism.

The realisation dawns that now not only is your local copy a risk, but so too is your cloud provider.

Your individual account, secured by yet another password, could be compromised in isolation.

Or the cloud provider themselves could be breached en masse. Vulnerable from within to underpaid technical support staff and opportunistic hackers from without.

When does the cycle of risk and mitigation end?

Adopting Two Factor Authentication (2FA) is a pragmatic way of reducing the risk of account capture. This provides a secondary “something you have” challenge.

Some people use their mobile phone number as a 2FA method. A time-limited one-time passcode or link is dispatched whenever somebody attempts to log into your account. Control the phone number, control the access.

This turns your phone handset into a single point of failure, especially if you have your smartphone logged into your email account. Many of us do these days.

Software 2FA token generators remove that SIM porting risk.

Tokens are generated on your device, never transmitted over a network.

Which was great. Until somebody figured out how to compromise them. Recent reports discuss both RSA SecureID and Google Authenticator having been allegedly breached by hackers.

Software tokens on phones fail to address the single point of failure risk.

It can also make future handset upgrades a traumatic ordeal. Trying to de-register the 2FA from the old device and re-register it on the new one is a non-trivial undertaking.

Hardware token generators provide another form of resilience. Once again, there is no network transmission of the tokens. This time the device is physically separate from your phone or computer.

Back in the olden days, SecurID tokens were widely used. Until their token generating algorithm on was leaked.

Today the modern-day equivalent of those old fashioned hardware 2FA tokens is a Yubikey.

The strength of a physical 2FA token pattern is you need to be able to physically touch it to use it.

The weakness of the physical 2FA token pattern is you need to be able to physically touch it to use it.

Forget or lose the token, and you are locked out of your account. By design.

Unless you printed out a copy of the backup codes. Which allow you to gain access, via a back door, in the unfortunate event that you lose your physical 2FA key.

It occurs to you that your house is vulnerable to fire or natural disaster, endangering your offline paper-based copy of those backup codes. Or, if you hadn’t bothered with all that password manager and 2FA shenanigans, the piece of paper you wrote down your original strong password upon so that you wouldn’t forget it!

Perhaps a safe deposit box is the answer? Assuming you can still find a provider who is willing to run the risk of having their vault full of illicit items. Trading convenience for physical security.

But what if you need access to the paper-based backup during a bank holiday weekend or while holidaying overseas?

Instead, you fold up that print out. File it away somewhere that feels safe, but remains close by. In your “go-bag” perhaps?

Then you realise that you have reinvented your father’s little black book security setup!

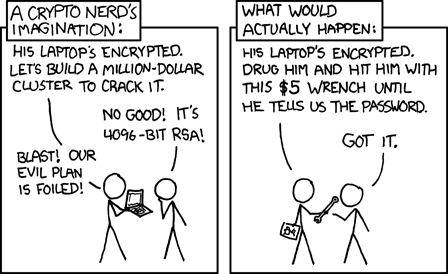

Which would fail the moment the moment the real threats start. A bad actor requesting access by breaking your fingers, or threatening your kids.

The truth about information security. Image credit: XKCD.

References

- BBC (2020), ‘Dropbox hack ‘affected 68 million users‘

- Cimpanu, C. (2019), ‘Chinese hacker group caught bypassing 2FA’, ZDNet

- Cimpanu, C. (2020), ‘Android malware can steal Google Authenticator 2FA codes’, ZDNet

- Finkle, J., Shalal-Esa, A. (2011), ‘Exclusive: Hackers breached U.S. defense contractors’, Reuters

- Krebs, B. (2020), ‘All About Skimmers’, Krebs on Security

- Kumar, M. (2019), ‘iCloud Possibly Suffered A Privacy Breach Last Year That Apple Kept a Secret’, The Hacker News

- Ponemon Institute (2019), ‘The 2019 State of Password and Authentication Security Behaviors Report‘

- Unger, J. (2017), ‘Thousands of deposit box valuables ‘cannot be traced to owners’, BBC News

- XKCD, ‘Security‘

GentlemansFamilyFinances 14 June 2020

My mum was recently nearly swindled out of all her cash savings by a “problem with your.internet” call.

The direct approach doesn’t worry me too much but the situation that happened to you could. Happen to anyone anywhere anytime.

I try not to worry about it but I recently purchased some anti virus for our phones and.computers because I believe it.might help (and even prevent it from happening.

However the risk is.is still there and like the Ermine says – I don’t trust the cloud.

I’ve no.idea what’s the best option.

{in·deed·a·bly} 14 June 2020 — Post author

Lucky escape for your Mum there GFF, I’m glad to hear it worked out ok in the head. Must have dented her confidence though, once she realised how close she had come to losing it all.

The cloud is a tool like any other, useful when used correctly, but potentially dangerous in the hands of those lacking the knowledge and experience to use it safely.

GentlemansFamilyFinances 14 June 2020

Yeah – she’s in her 70s so she’s had to learn about computers and whatnot. Confidence truly shaken.

John Smith 14 June 2020

An idea which I successfully tested and implemented:

keep the money in few countries [2-3] in our family member names [2-4 persons]. So already 10x less money/person/country. In each country few independent banks [3-10]. Plus near empty account like “Revolut” to move between countries/curency etc.

keep only few amounts in current counts [50-500]. All other big money is in fix-term accounts [2-5 years]. Before fix term account mature open a new temporary account and nominate it as recipient of the mature bond.

All passwords noted in an encrypted spread-sheet, but only with few symbols, rest is **”stars”; and of course 2-3 mobile-phones for authentication 2FA.

It is a hassle, but better than sorry. It seams paranoid, but sleep well in night.

{in·deed·a·bly} 15 June 2020 — Post author

Thanks for sharing your setup John Smith.

I think security is always going to be about compromise, choosing the least worst combination of options.

The folks inventing new security mechanisms and techniques are just as smart as the folks who seek to beat them. Often the same folks. It is an arms race of sorts.

The only certainty is whatever best practices we put in place today will no longer be considered “best practice” in 10 years time. The best we can hope for is to adapt and evolve our approach as vulnerabilities are discovered and reported.

John Smith 15 June 2020

My human capital will decline, others are smarter. My job is to bend the known rules, the weak security by obscurity. Multi-layer defense, avoid to be targeted.

1. No income tax, no inheritance in any (?) country (poor on paper, personal allowance, etc).

2. Nobody (?) wants to kill me, to kidnap, to blackmail. (locked /spread money).

3. Family loves me (?), I already “donated” to them. If they want more, they keep me alive and healthy to benefit from my future pension also.

All I can do is to put diverse type of road-block on financial pipelines. So attacker time is not worth his effort, hoping he chooses another target.

(# indefensible, # war games, # predictive, #enough 😉

[HCF] 15 June 2020

Sorry to hear about that. Very interesting read. These kind of stories scare me as being someone who sometimes losing his phone or wallet…

I think one of my university professors said who was a security expert that we should have no illusion, there is no uncrackable security just one which is not cracked yet. We should not aim for having a system which is impossible to crack but one which makes the effort of cracking it not worth the hassle.

Generally I tend to use my skeleton key email as few places as it is possible and I have dump mail accounts for the rest. Also having logins as few places as possible can help too.

Once one of my colleagues asked me how to have an unforgettable secure password. My answer was that you have to learn a process by head to reproduce it thus you won’t forget it.

For a start pick a string which you probably won’t forget (the name of your first pet or something like that), this will be the seed. Then feed it to a hashing algorithm and get a hash string. Then pick a process you want to apply on it to generate the final password you want. For example take 12 or 16 characters of it, from the start or from the end forward or reverse order. Done. Oh, and don’t write this down anywhere 🙂

Thus you should only ensure that the process should be simple enough to know it by head. Of course this is not an easy process so I would use for securing master passwords or skeleton keys. Otherwise I also use a password manager for other stuff but as you wrote, most of those accounts can be regained using your primary email address. So that is the point which you should protect the most in my opinion.

John Smith 15 June 2020

“… use my skeleton key email as few places as it is possible and I have dump mail accounts for the rest. Also having logins as few places as possible can help too.” <– excellent! me too, K.I.S.S.

– dump email for subscription, just buffer for temporary confirmations.

– fake/generic user-name + details; pets/fake photos to my "profile"

– no LinkedIn, Facebook, Tweeter etc

-pay with a free TEMPORARY/virtual REVOLUT debit card, then destroy/delete it after you received the good, or you took the paid holiday.

{in·deed·a·bly} 15 June 2020 — Post author

Thanks for the suggestions HCF. Your professor was wise, I completely agree with them.

I think the attempted purchase fraud this week is unfortunately something that none of us can reliably prevent. A NFC transaction requires no authentication. A transaction using something like ApplePay requires a quick face/fingerprint scan or entering an easily observed PIN code. Different merchants have different criteria for processing online card transactions, the long card number and expiry date are must. Others require the CVC code and/or billing address.

Managing our credentials is a different matter.

I used to apply a comparable method for generating unique strong passwords that I could either reproduce or remember. It wouldn’t have stopped individual accounts from getting breached via a merchant data leaks or brute force attacks, but it did limit the blast radius of those inevitable breaches.

However, while my method wasn’t written down anywhere, I became increasingly conscious that it was this very repeatability that was the weakness in my password approach. I have since moved on.

Ever paranoid, I had long secured my primary email account using an entirely different method to mitigate that specific risk.

BeardyBillionaireBloke 19 June 2020

Definitely can’t overlook the possibility of crooks inside a financial organisation.

{in·deed·a·bly} 20 June 2020 — Post author

Thanks BeardyBillionaireBloke.

Having worked in a few of them, I concur.