That feeling of existential dread.

Emerging a little as the weekend draws to a close, Sundayitis.

Experienced towards the end of a holiday, particularly the Christmas break with all its talk of new beginnings.

We get it while sitting in the waiting room at the dentist. When organising life insurance or a legal will.

Or in this case, while reviewing my finances.

Not the mindless updating of tracker spreadsheets. Nor the unthinking production of pretty charts.

No, the part I dread is the analysis. Critical assessment. Having issues brought to my attention.

Once seen, they cannot be unseen. Ignorance shattered, blissful no longer.

Something needs to be done. Action required. Changes made. Difficult conversations had.

Rationally, we know it won’t be as bad as it feels. Dishearteningly, it will be pretty much as we expect.

Dragging my inner saboteur kicking and screaming to sit down and do the work. Forcing myself to grind through it, wise to the endless tricks, excuses, and procrastination. Rabbit holes to go down. Distractions found. Desperate to be anywhere but here, in the moment, discovering inconvenient truths and thinking through their implications.

The irony of this is not lost on me, given that every now and then I write about personal finances.

In part, the dread comes from already knowing, roughly, what the numbers will say.

From suspecting that I won’t like the tale they tell.

After all, it was me who was doing the investing, saving, or spending. But that was down at the micro-level. Individual transactions. Hiding amongst all that noisy detail.

The menu of headline figures are many and varied. Allowing the humble blogger to cherry-pick those that support their narrative or inflate their ego.

Net worth up. I’m an investing genius! All alpha, baby! Maybe I should write a book…

Income up. Smarter, better looking, and more valued than ever before!

Others are less flattering. Excuses found. Explained away. Or not mentioned at all.

Expenditure up. Blame the government. Curse the Fed. Inflation, inflation, inflation.

Savings down. One-off this, COVID that. Treat myself, I deserved it after a tough year.

The reactions proving more instructive than the numbers. Irrational human behaviours are fascinating.

I caught myself exhibiting several of these behaviours. Grimacing at the expenditure figures, then making excuses.

“Capital gains tax on the disposal of a property, but I won’t be doing that again any time soon…”

“Nanny wages, but the younger child will age out of needing school pickups in a year or so…”

“Gift budget blowout, but I didn’t take any international holidays this year, so it cancels out…”

After spending a few minutes massaging my numbers into a more palatable reflection of normal I stopped and laughed at myself. What was I doing? When is any year ever “normal”? The specifics and timing may be unpredictable, but some random “life happens” events are bound to occur.

So I stepped back. Zoomed out. Adopted a broader perspective.

First, aggregating each category of numbers by year.

Second, adjusting each annual aggregate for inflation. By bringing each number to a common current purchasing power basis, it allowed me to distinguish between my own lifestyle inflation and externally imposed economic inflation. The former is within my control, the latter not so much.

The result allowed for a meaningful analysis of trends and time-series comparisons, as opposed to the nominal nonsense often served up in year-end summaries. The interesting part isn’t the numbers, but how they feel, which only inflation-adjusted numbers can provide.

Third, I calculated some averages to provide a basis for projecting into the future. The averages were calculated over the last decade, to smooth out genuine one-off peaks or troughs, and to ensure a more representative sample than that provided by these recent COVID years alone.

What did I learn?

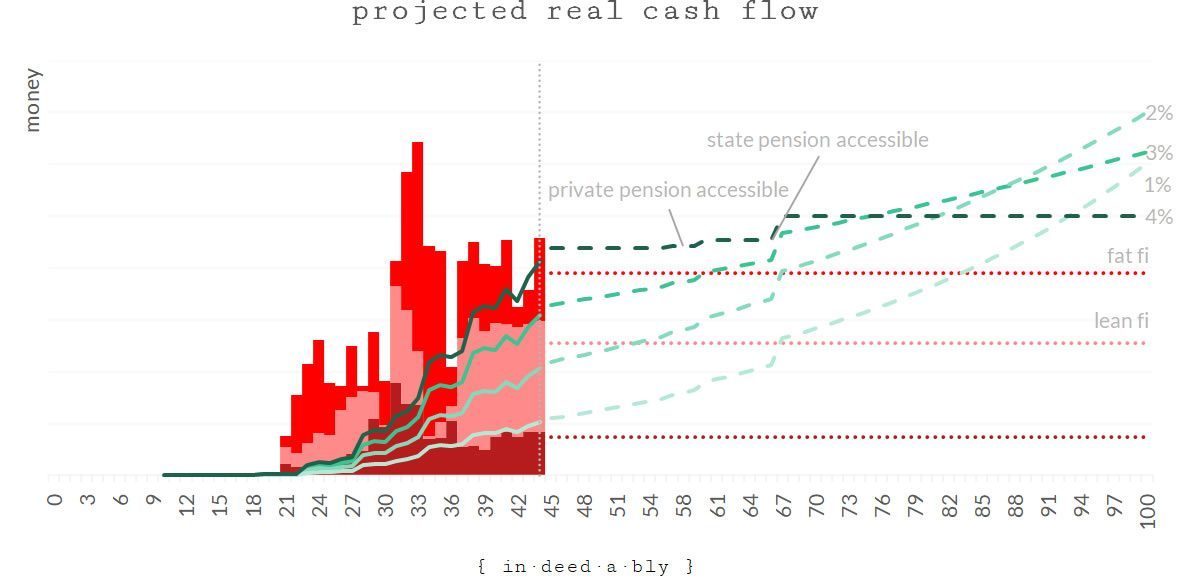

My inflation-adjusted needs and housing costs, which combined might represent a “Lean FI” baseline, have been largely consistent since my younger son graduated out of nappies. This surprised me.

Meanwhile, my inflation-adjusted wants had bounced around like a sugared-up toddler at bedtime. This didn’t surprise me. The main variable being vacation spending, particularly trips home during peak school holiday periods. Adding wants to that “Lean FI” figure would get me to a rough “Fat FI” baseline, though one that optimistically but shortsightedly ignores taxes.

Out of curiosity, I decided to model how one of the retirement funding approaches commonly espoused by segments of the FIRE community might play out.

Coast-FI. Unfortunately, this one doesn’t result in beachside living, but rather is where a person decides they have already invested enough to fund a comfortable retirement in the future. From that point onwards, they save no more, preferring to coast their way towards retirement as time and compounding returns do the heavy lifting for them.

A key assumption built into this approach is the level of anticipated returns that will be achieved. Bloggers commonly cite a proxy, such as the S&P500 Total Return. Since its inception nearly a century ago, the headline S&P index produced an average annual total return of roughly 12%.

Except for most of us, this number will be optimistic. The index doesn’t suffer the drag of a multitude of anchors that investors may. Management fees. Platform fees. Brokerage fees. Foreign exchange fees. Withholding taxes. Dividend taxes. Capital gains taxes.

Few will have their entire net worth concentrated in US Equities, perhaps diversifying into bonds and/or global equities. Many diversify further, across asset classes ranging from property to crypto.

So if a 12% projected return before accounting for fees, taxes, and inflation is high, what would represent a reasonable proxy after all those fees, taxes, and inflation have been taken into account? This will be a subjective judgement call, with every person arriving at a different answer.

In my case, I looked back over the records documenting my 30+ year history of investing. An evidence-based figure is going to be a better guide than any number I made up based on solely upon selective memory and wishful thinking.

It turns out my average annual nominal gross return was just over 12%, comparable to that S&P500 total return figure, though I remember it requiring more work than riding a passive index tracker.

Crunching the numbers, I calculated how much I had paid in taxes on investments over the years: more than £500,000, ouch! Mostly stamp duty and capital gains tax on property investments, wealth taxes both, and diabolically difficult to avoid back when I still thought residential landlording in London was a good idea.

Sometimes I wonder whether those landlords swimming in the shallow end of the market in Northern England, where properties are priced below the stamp duty threshold, may not have been the smart ones? Then I remember how many properties would be required to make any real money, and the resulting quantity of tenancy hassles involved, before concluding the high-value low-volume approach was probably the right one for maintaining my sanity!

Next, I worked out a rough number for unrealised capital gains on investments I still held and which had appreciated in value. From that figure I calculated a provisional capital gains tax liability that would be due were I to liquidate my portfolio. It was an eye-watering sum, one that made me want to escape to my happy place.

Finally, I totalled up all the various fees and charges incurred in acquiring, holding, and occasionally disposing of investments I’d held over the years. It was heartening to observe how much fees have reduced over time, as competition and technology have changed the financial services landscape, mostly for the better.

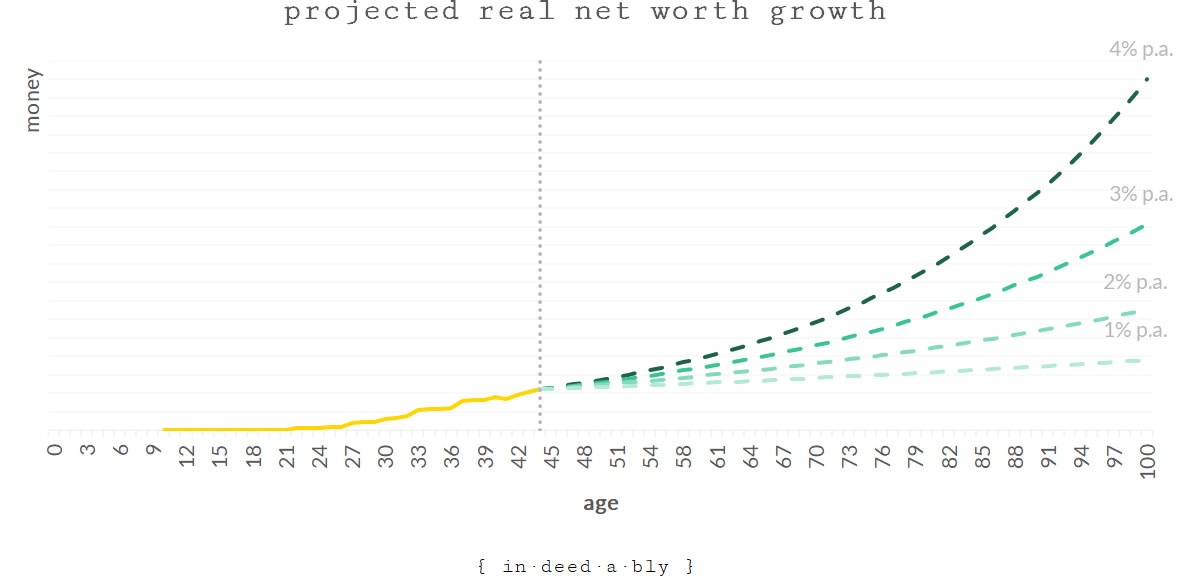

It turns out I have averaged an annual return of between 4% and 5% after fees, inflation, taxes paid, and taxes notionally payable. Regardless of whether that outcome is good or bad, it is a world away from a naïve expectation of coasting into retirement based on earning a 12% compounding annual return.

Some of that damage could potentially be mitigated using tax-advantaged or tax-exempt investment accounts, keeping an eye on fees, and liquidating assets gradually rather than en masse. That said, it would be difficult to sell off annual slices of investment property, and (unlike Australia) it isn’t currently possible to hold an English property within a tax-advantaged pension wrapper.

The bottom end of that return range was 4%, coincidentally the same figure many within the FIRE community base their retirement numbers upon.

Which raises another key assumption, this time of withdrawal rates.

In this fantasy land of projections, where trends are linear and returns predictable, running a 4% withdrawal rate over a portfolio generating a 4% annual real net return would consume all future growth, leaving the original capital amount intact but capping future income streams.

Unsurprisingly, a lower withdrawal rate starts out with a lower income initially, but as the compounding growth of the residual invested amounts steadily increases, so too does the annual amount paid out for the FIRE-seeker to live on. In time, the income paid out by a 2% withdrawal rate would exceed that of 3% and 4% withdrawal rate strategies, assuming we live long enough to see it. The difference between enjoying cake today versus having cake tomorrow.

How accurate are those numbers? Not very. The only certainty is that the future will look nothing like them.

Over my 30+ year investment career, I’ve had three down years where I finished the game with less than I started with. Which was bruising to my ego, but fortunately not the end of the world. It did teach me that market returns are both variable and outside of my control, no matter how much I may have once believed it were otherwise.

On average, these numbers paint an attractive picture, but nobody lives the average.

Some years, a withdrawal rate will look ridiculously conservative.

Other years, that same rate may appear insanely generous.

It all averages out in the end, reverting to the mean, but with no guarantees that will occur within our preferred timescales or indeed within our lifetime.

Based on these projections, I might be financially independent already.

Assuming the assumptions hold up.

Assuming the future is as simple and predictable as my spreadsheet would have me believe.

Assuming my net worth remains allocated to productive investment assets, rather than spent on dream houses, Tesla cars, and rides in Jeff Bezos’ rocket ship.

And assuming it remains largely intact. Not decimated by divorce. Nor depleted as the Bank of Mum and Dad.

That feels like an awful lot of assumptions, several of which I wouldn’t bet my financial future on.

Not yet anyway.

References

- Slickcharts (2022), ‘S&P500 Total Returns by Year‘

GentlemansFamilyFinances 7 January 2022

You’ve said everything I’ve been through this week (just with bigger numbers! + Where provided)

Great post from then perspective of someone who has thought deeply about their finances and what the hell I spent it all on last year (£1,000 on Belgian beer in my case)

Glad to see a look ahead on aprés-nappy household spending. We’ve dispensed with the nanny and WFH and small city living allows us to be there at drop-off/pick-up for the kids but there’s a minefield of spending ahead.

For you, you’ll see the end of kids at home and as dependants soon enough? To think that you are not FI is a bit rich considering how many people won’t be able to turn on the heating this time next year.

This from a CoastFI family man whose appetite for going the extra mile has been lost – and deeply buried alongside my S&P500 tracker funds that swing the pick for me while I’m living the rest of my life.

{in·deed·a·bly} 8 January 2022 — Post author

Thanks GFF.

Unless your kids go to private school, my experience has been the kiddie spending tapers off once they graduate from nursery. After school nannies are still expensive, though after-school care are perhaps a cheaper option. That said, holidays get a lot more expensive, particularly once squeezing into a single hotel room is no longer survivable.

I challenge your premise here. FI is a feeling, not a number. A big part of that feeling is relative to where a person lives. I’d certainly be FI in most of the world. I could probably be the king of somewhere like Nauru or Palau. But in the expensive part of London where I currently choose to live, not so much.

As you correctly observe my kids will (probably) have flown the nest in 10 years time, around which point my long term plans involve moving somewhere warmer, coastal, and probably with a lower cost of living. Off the same asset base I would expect to feel FI there, even after I trade some of those investments for a non-productive home to live in. But the future is unwritten, and life happens events often alter our course, so it will be interesting to see how things play out.

Liz 8 January 2022

Like GFF, I am on Coast FIRE too with two young kids. Would love a third, though not sure if I want to work those extra hours to fund a third….

Good to hear the spending drops off post nursery years. Although we just had a ski holiday and 3 people + 1 baby is a lot more expensive than just 2 adults, dreading having to pay for 4 people (or even 5). Not sure how to work this into my projections… double our holiday costs?

And while I would love to be able to send my kids to private school, I don’t want to work those hours either. Currently doing 2 days a week at work and that’s 2 days too much! After having escaped the corporate rat race, it feels awful going back.

We have been willfully blindly optimistic about our FIRE projections — haven’t adjusted for inflation, or fees, or taxes. I don’t suspect I would like the ‘real’ answer…

{in·deed·a·bly} 8 January 2022 — Post author

Thanks Liz. Good luck with your future plans, I hope you find a balance that works for you.

I must confess to chuckling when I read about your expensive ski holiday. Within my elderly mother’s social circle, “ski” is an acronym for Spend the Kids’ Inheritance. In the days before COVID, the old folks would take great delight in jetting off on expensive coach tours and cruises, enjoying the fruits of their lifelong careers, while imagining the dismay on the faces of their offspring as the size of their eventual inheritance windfall diminishes before their eyes!

Full Time Finance 8 January 2022

Honestly I’m struggling with the projections lately but I’m the opposite way. Covid has reduced our expenses in several areas. But my projections say that the level I’m down too is not real in a normal year. I haven’t made a change so I trust my projections more.

Somewhat related, No nanny but sports teams replaced child care at some point so I’m not convinced that changes that much around expenses with kids. They just change in type.

{in·deed·a·bly} 8 January 2022 — Post author

Thanks FullTimeFinance.

I think the child related expenditure depends greatly on the family. Some kids have expensive hobbies, others don’t. Raising a Lewis Hamilton or Serena Williams is no doubt far more costly than the average screen addicted teenage couch potato!

The COVID years have been a varied experience. Good in the sense that they have got me to think about projections, something I had never worried much about in the past. The last few years, I’ve just roughly figured out what passive income my portfolio would generate in the coming year, then done a winter working hibernation to bridge the gap between that and my lifestyle costs. So no savings, just making up the difference while my capital (hopefully) compounded happily in the background. I guess that could be described as a form of semi-retirement + Coast-FI.

John Smith 9 January 2022

My own “fantasy projections”, all values in nominal (not inflation adjusted) to help me with tax optimizations — geo arbitrage:

– death at age 95 (yield -2% aka negative, all net-worth in cash, value= near zero);

– age 80, lost math skills and pleasure in money management, yield 0%, cash/bond ratio 20%/80%;

– “linear” yield decrease from now, initial (5%?) to 1% at age 75.

– the yield is for the rest of the net-worth after the yearly consumption.

– yearly withdraw for consumption rises with my “personal inflation”;

– yearly personal inflation is a “inverted keep water” U – curve, from 60 to 75

age.

I did not see many sane pensioners preoccupied with their investment management in their old age. Pensioners were/are risk adverse, and they have an annuity (the pension), plus eventually a house.

So, I do not count on increase of yields with age. For me, if I will be age 75, I will not give a f**k for any extra money over gifts for kids and my small limited pleasures. YMMV.

{in·deed·a·bly} 10 January 2022 — Post author

Thanks John Smith. You raise several excellent points.

Cognitive decline is something that will impact most of us. Simplifying things before that becomes an issue is a good call. Whether it is losing the ability or the interest, I’d hate to still be battling complaining tenants in my dotage.

The “U” shape expenditure is also very valid. After early years/nursery care for our children, our own aged care is likely to be the next most expensive phase of our lives. For some of us this won’t be a problem, not waking up one morning. For the rest, it could be years (or decades) needing carers, meals on wheels, nursing care, or eventually residential aged care. It isn’t something that gets talked about as much as it should in personal finance circles, given the relatively young age of the writers, but that doesn’t make it any less of a potential reality later in life.

David Andrews 10 January 2022

Assumptions and projections are tricky things. A couple of months ago I had a financial review through my employer. It was one of those “off the shelf” things with an employer appointed “finance professional” who dutifully plugged in the numbers I supplied to his software.

He asked me what I believed my current spending needs were and then fell rather quiet, I don’t think he believed the number I supplied. His software produced some figures and graphs for “normal” retirement age and then he suggested we look at retiring at “55” just for fun.

I’d already produced my own numbers “just for fun” and I was pretty certain our conclusions would be the same. I’m definitely coasting, I’m probably going to overshoot the FI landing zone.

Like other posters on this thread, I’ve become rather disengaged from my paid employment and I take some comfort in the numbers in my spreadsheet.

I think I now need to make sure I’m retiring to something I want rather than just retiring from something I really don’t want.

I also need to establish the merits of pension bridging by drawing funds from my fully offset interest only mortgage versus my investment ISA.

Logically I should leave the investment ISA untouched as long as possible and plunder the mortgage instead ( potentially repaying it with pension tax free cash ) – it’s an emotional issue rather than a logical one.

weenie 10 January 2022

I love and hate reading these kinds of posts.

I love reading all the detail and really appeciate the thought, time and effort put into the analysis and then laying it out into an interesting read.

I hate that it reminds me that I should be doing similar detailed analysis on my own numbers but my mind shies away and just files it away as something ‘to do’!

I have however considered cognitive decline in the future, so at some point, if there’s still money in the FIRE pot, I can see that being converted into an annuity as keeping track of dividend income and updating spreadsheets will no doubt be a chore too much for an addled brain.

{in·deed·a·bly} 10 January 2022 — Post author

Thanks Weenie. Sounds like your reluctance to do the analysis parallels my own.

Shifting to an annuity sounds like a sensible approach. The hard part is knowing when to pull the trigger. Going too early costs returns and incurs taxes. Leaving it too late risks not having the marbles remaining to make it happen at all.

All the 90-somethings I know, it would be beyond them to do the thinking, understand the paperwork, and make it happen.

Most (but not all) of the 70-somethings I know are physically wearing out but still as mentally sharp as they ever were.

One unlucky lady I know suffers early onset dementia, beyond her already in her mid-50s.

John Smith 11 January 2022

Mentally sharp does not mean the old person is willing to learn new (complicated) things like new rules, (tax) laws. Physically wearing will generate a lower optimism. Focus at age 70+ is on good food and family relations, not money, I saw.

Generally speaking, at age 70, your child is age 45..50, already married, half-paid mortgage, and near his peak earning potential. You human capital will be .. low, as seen by crowd. Your money net-worth will become target for inheritance.

IMHO, best approach is to donate to child (your future care-keeper?) when they are young and need your money. At their age 45, they will not need your money.

Spreading your money early, you can then focus more on future your-self. You’ve done your human-part, and market risk is less for low net-worth.[Plus let the any state to do its protection promise]. This is not my advice to anyone, it’s just my approach to life.