I received some bad news this week. In the scheme of things, it was nothing major. No terminal diagnosis. No death notification. Nor had I learned that my favourite chocolate biscuits had been discontinued, or that my football team had lost yet again.

No, this was your everyday bad news. An inconvenience. Leaving me a few thousand pounds out of pocket. Hopes thwarted. Dreams delayed. “Nothing personal. It’s just business”.

That thought stopped me in my tracks. Notions of plotting unspeakable revenge, rage quitting, or throwing a five-alarm toddler tantrum instantly forgotten.

Losing a few thousand pounds was just an inconvenience. When had that happened?

I remember a time, not so long ago, when such an outcome would have been life-changing. An unmitigated disaster. Instigating a spiral of hardship, homelessness, and eventual deportation.

But what was once true, is no longer.

Some combination of good fortune, good management, elapsed time, and compounding had allowed me to weather this storm with little more than a bruised ego and an expensive reminder that life happens.

When had that changed? As part distraction, part effort to cheer myself up, I decided to crack open my historical financial records and perform some self-indulgent digital archaeology to find out.

Everyone is a genius

Back in the early 2000s, I used to enjoy watching television property porn. There was this one show where aspirational amateurs would buy a property, waste loads of money on renovations that added no value, then try to sell at a profit. Each episode would conclude with a narrator smugly informing the audience that the amateur developer had been rescued by the rising market, as comparable properties had recently sold for the same (or higher) amounts without the renovations.

That lesson proved to be a valuable one. Teaching me to distinguish between correlation and causation. Was a given outcome the result of my own actions and decisions, or in spite of them?

All too often, we hear people crowing when frothy markets soar and booming returns go their way.

Many of those same people will seek to shift the blame when things go against them.

The markets. The government. The economy. The competition.

Unforeseeable, rather than unforeseen.

Unavoidable, instead of unavoided.

Never choosing to admit, even to themselves, that they might be responsible for an adverse outcome.

As for the rest, all but a few remain silent about their losses. Celebrating their wins in public. Licking their wounds in private. Carefully crafting an aura of infallibility, as false as any social media profile.

Before evaluating any personal journey, it is important to first understand the big picture within which that journey took place. When everyone looks like a genius in a rising market, distinguishing between the lucky and the good can be challenging indeed!

To paint that big picture, I’ve used statistics local to where I find myself today. Telling a slightly different story to where my journey unfolded, but representative enough to provide a backdrop for my journey. The tale commences from the point that I started tracking my finances and paying attention.

Interest rates were a problem until they weren’t. Helping savers. Hurting borrowers. Then the Global Financial Crisis tipped the world on its head, reducing borrowing costs to virtually nothing, while the purchasing power required to repay debts was steadily deflated away. Shifting the debt conversation from one of avoidance and minimisation to recognising a once in a lifetime opportunity for wealth creation.

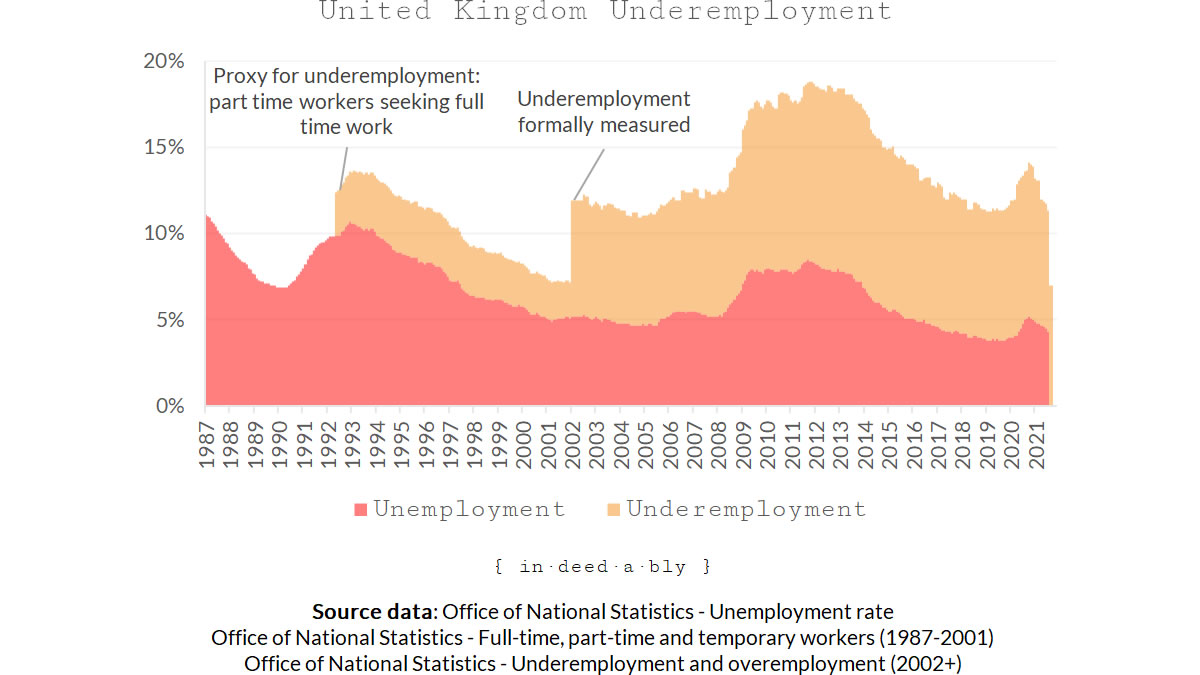

Unemployment was once thought to be the problem. Portrayed as that unfortunate underclass of society who notionally wanted work, but were unable to secure it. Then questions started to be asked about underemployment. That segment of society who have some paid work, but actively seek more. The latter group has proven to be a problem consistently larger than the former. Hidden in plain sight. Seldom discussed. A large pool of excess capacity for which society has found no productive use.

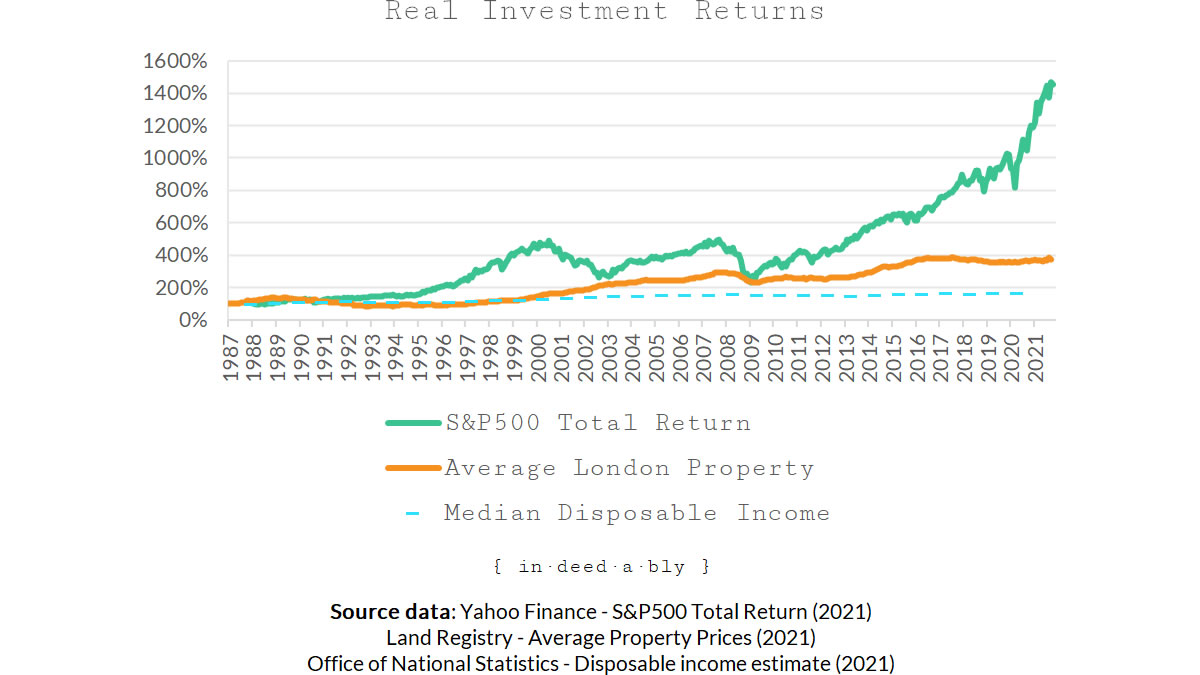

Investments take many forms. Depending on your perspective, three of the most common investment classes might include your home, your marketable skills, and your portfolio. But which class of investment has provided the best return on investment?

This seemingly simple question has a somewhat complicated answer. Taxes play a major role in the equation. Salary earners pay a lot. Homeowners pay a little. Investors get to choose whether they pay any at all.

Comparing inflation-adjusted returns for these three investment classes over the last 34 years was surprising. Median household disposable incomes didn’t even double. Average London property prices grew almost 4x. Meanwhile, the total return of an S&P500 tracker grew by more than 1400%.

One thing is clear, those who are unable or unwilling to invest were left behind.

Look how far we’ve come

My financial journey began as a paperboy. Delivering newspapers and junk mail all around my neighbourhood. In sweltering 40 degree summer days. Mind-numbing sub-zero winter nights. Getting the job done while evading rain, neighbourhood bullies, stray dogs, and territorial magpies.

The pay was not good, but the life experience gained was priceless. It provided a valuable baseline against which all that followed could be evaluated.

Would the role require heavy lifting outdoors in the rain?

Who benefits more from my efforts? The employer? The tax authorities? Or me?

Did the position offer autonomy? Meeting deadlines however and whenever I pleased?

Were the financial rewards received linked to the effort expended, or the outcomes achieved?

What were the potential second-order effects and long-tail impacts of undertaking the role?

Hidden consequences.

Opportunity costs.

Unanticipated benefits.

Was I likely to establish the contacts and gain the skills which would subsequently allow me to get lucky by being in the right place at the right time, and actually being able to do something about it?

With the benefit of hindsight, I probably should have stayed a paperboy. But if I had, then I would never have afforded the many adventures and experiences I have enjoyed, or endured, in the years since.

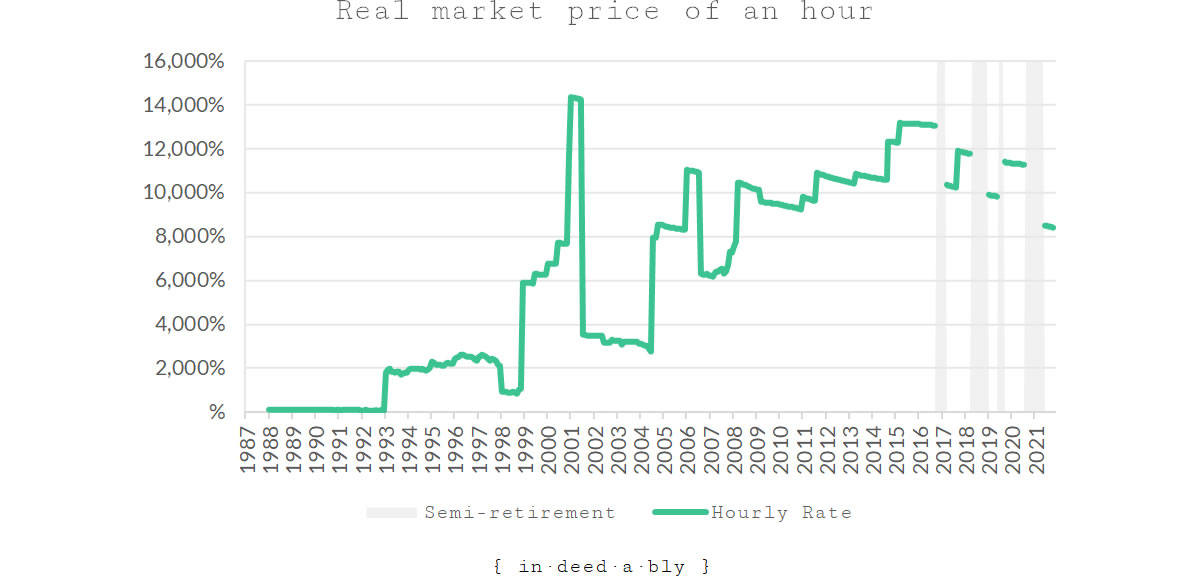

The next chart shows the inflation-adjusted market price that an hour of my time has commanded. A fascinating picture with a far more interesting story to tell than my earnings over time. Detailing fleeting moments where I was on top of the world, possessing rare skills that were highly sought after. Terrifying moments, when changing fashions or technological disruption found me selling a product nobody was buying. A change in priorities, buying time with forgone earnings rather than selling time to make ends meet. Consciously purchasing temporary freedoms and a more balanced lifestyle.

Take a moment to compare this chart to the earlier one, illustrating real median household disposable income over time. A timely reminder that nobody lives the median, and nothing lasts forever.

We start our working careers knowing little and earning less.

Over time we gain knowledge, skills, and experience. Gradually becoming useful. Able to solve real problems. Our earnings climb to reflect the increased market value of our time.

Sooner or later, we top out. Reach the limits of our abilities, competence, network, and relevance.

Those limits might come from within, or be imposed from without. The outcome is the same.

A lucky few finish on top, like a sportsperson retiring after winning a gold medal or championship.

Most will peak, then decline. A gradual reversal, or abrupt cliff edge of displacement and redundancy.

That median disposable income figure may not have changed much over 30+ years, but the financial positions of those individuals being sampled throughout certainly will have as they age and grow.

Now let’s cast our minds back to the start of our journey to observe the series of paradoxes that faced us.

We earned little, with aspirations to save a lot.

We had little, which was ok providing we don’t know any better.

Living within our means was excellent advice, yet how we felt about that was governed by our conditioned perception of normalcy. Our upbringing and the socio-economic status of our peer group initially defining that perception. The wealthier we grew up, the better appreciation we had for what was possible, but the higher we set the bar for how much is “enough”.

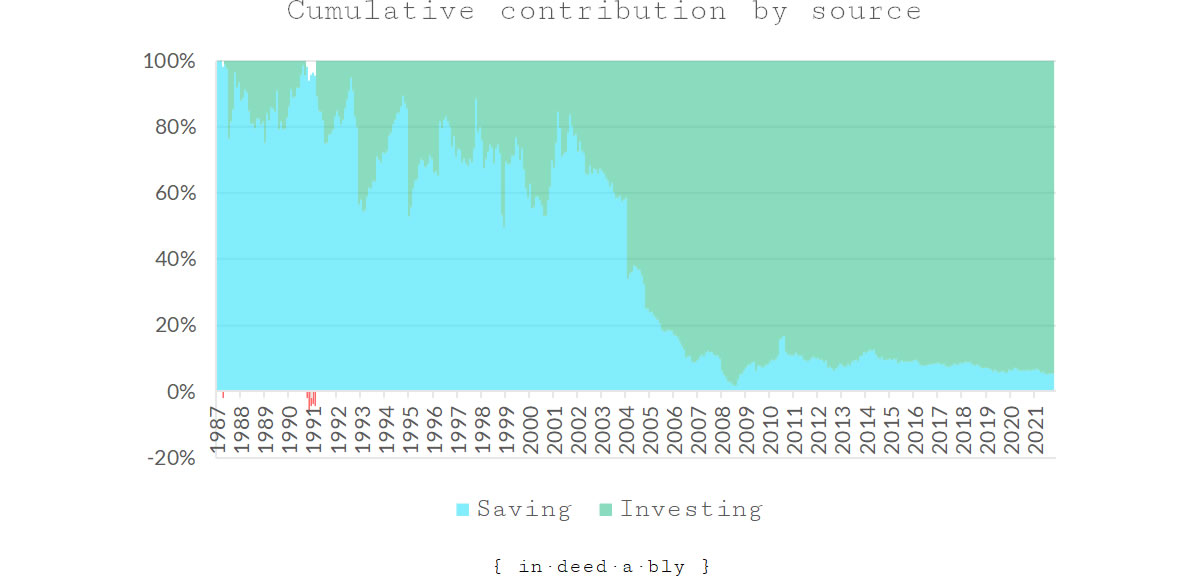

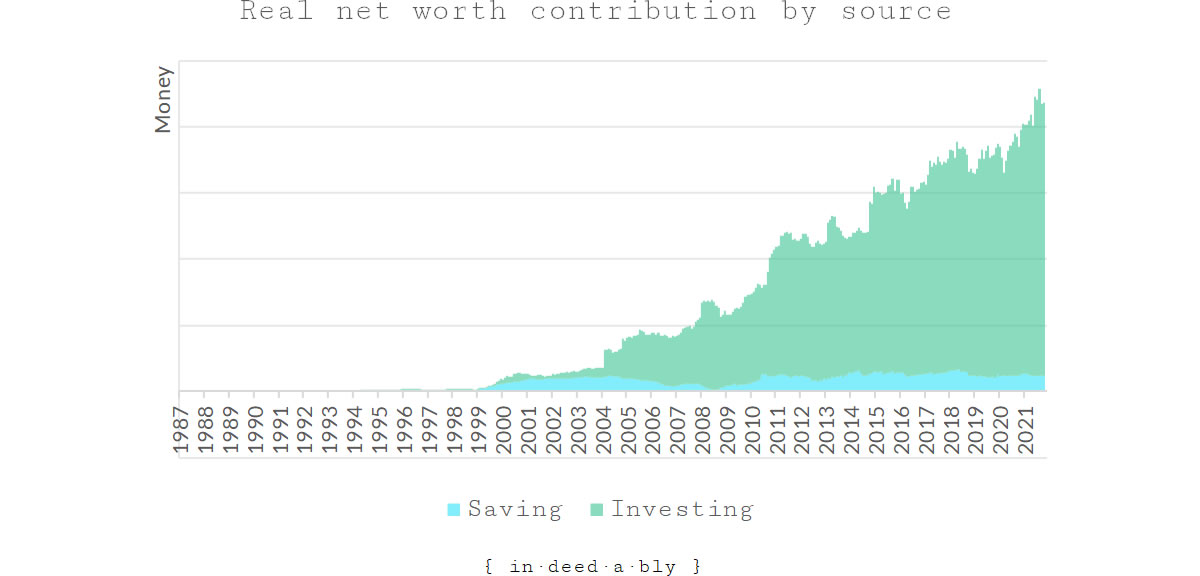

In the beginning, savings are everything. By the end, savings have long become irrelevant. A journey that can be illustrated with a chart visualising the proportions each has contribution over time.

Savings and frugality are the primary tools deployed by those just starting out and those who don’t know any better. Indeed, we express saving rates as a proportion rather than an absolute number to pump up our tires and spare our fragile egos, “saving 50% of my income” sounds much more impressive than “saving £15” even though both may be factually correct.

However, investing and compounding soon render those savings immaterial. If we invest our savings wisely, then leave them alone, things tend to compound relentlessly.

Investment growth first supplements our earned income.

Then matches it.

Before eventually surpassing it entirely.

A journey that would not have been possible without those initial savings, nor without advancing along the financial maturity curve and taking the leap into the world of investing. A potentially scary juggling act. Trading off adventure versus adversity. Capital versus conservation. Luck versus loss. Risk versus reward. Speed versus safety.

When I look at how far I’ve come on my own personal finance journey, after stripping out the effects of inflation which make us look richer without making us feel richer, I realise just how important seizing those investment opportunities has been. Today, over 95% of my net worth has been generated via acquiring and managing properties. Owning and running businesses. Buying and holding shares in a small collection of individual companies and low-cost index tracker funds. Carefully using leverage.

Which made me feel slightly better about having been stung for a few thousand pounds. As the old lottery slogan used to say, “you’ve got to be in it to win it”.

A feeling, not a formula

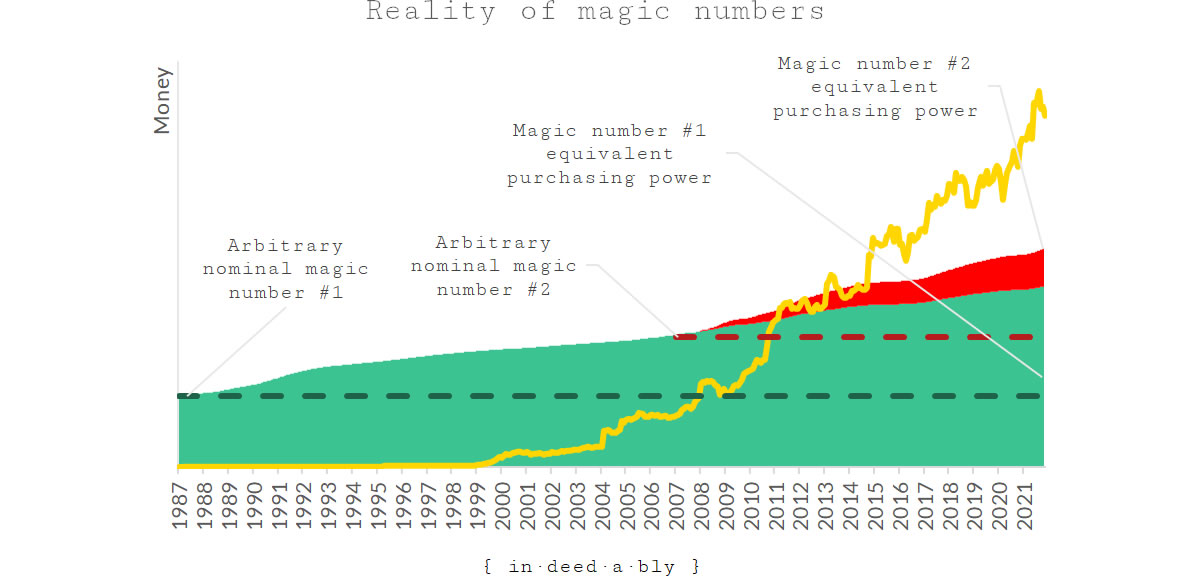

Before I let myself get a big head, I assembled a final chart to remind myself that no matter how far I’ve come, there is always further to go. Just maintaining the status quo requires effort.

As a boy, I had picked an arbitrary round number to aim for. To my simple mind, it represented winning the game. More than enough. Gaining independence from finance.

What I failed to appreciate at the time was that magic numbers are really moving targets. In the many years between setting and attaining that goal, the purchasing power of my magic number had been eroded by inflation. By the time I had reached my goal, the amount required to achieve the original purchasing power it represented had more than doubled.

Ever the slow learner, I immediately set myself another arbitrary round number to pursue. In one of life’s delicious ironies, by the time I reached that second goal, I still had not captured the purchasing power of my childish dream.

Today, the purchasing power of my dream would require nearly 3x the original nominal amount.

Eventually, I recognised that while bragging rights may be found in attaining arbitrary round numbers, seeking contentment in them is a fool’s errand. Which is fortunate, because achieving those goals produced a hollow empty feeling rather than magically conferring the sense of security I had sought.

Much like knowing how much is enough, our sense of financial security comes from within ourselves rather than from our net worth spreadsheets or portfolio balances.

A realisation that illustrates better than any chart just how far I’ve come.

References

- Land Registry (2021), ‘UK House Price Index‘

- Office of National Statistics (2021), ‘EMP01 SA: Full-time, part-time and temporary workers (seasonally adjusted)‘

- Office of National Statistics (2021), ‘EMP16: Underemployment and overemployment‘

- Office of National Statistics (2021), ‘The effects of taxes and benefits on household income, disposable income estimate‘

- Office of National Statistics (2021), ‘Unemployment rate (aged 16 and over, seasonally adjusted)‘

- Office of National Statistics (2021), ‘United Kingdom population mid-year estimate‘

- Yahoo! Finance (2021), ‘S&P500 (TR)‘

David Andrews 9 December 2021

It’s strange that financial pitfalls that may have proven catastrophic to our earlier selves are later only considered mere pebbles on the road. Some may advise that much of the income / net worth may be classed as unearned income (Guardian readers mostly) whilst we know that our positions may have been the result of risk taking, nerve holding and sacrifice compounded over a number of years. Also helped sometimes by global trends.

In the past 2 weeks 2 members of my team of 6 have resigned. This is going to significantly increase workload, weekend on call coverage and subsequently domestic issues for those who remain. I know of another 2 team members who are on the verge of leaving and I’m one of them. My past self would have considered resignation with little intention of taking up another job in at least 6 months ( in a pandemic ) as lunacy. In contrast, my present self sees it as an entirely rational thing to do. You’ve come a long way baby.

{in·deed·a·bly} 9 December 2021 — Post author

Thanks David.

I think it is a question of scale. Today’s pothole were yesterday’s chasms. We’re certainly not immune from peril, it just requires a catastrophe sized one (or a serious run of bad luck) to have the same impact these days. They still happen, only less often.

“Unearned” is an overloaded term. Correct in the sense we didn’t sell our time to produce the income. Yet not entirely effort free, and never risk free.

Good luck traversing the changes at your work. Sounds like you’re in a strong negotiating position if you didn’t want to leave, 33% capacity down with more headed towards the exits. Time to start haggling!

David Andrews 9 December 2021

Thanks for the response. I sometimes dip into the comments in the Guardian and Telegraph to observe the response to the money columns.

The Guardian tends to become a little “militant” (who would have thought it) and the term “rentier” gets deployed quite often. Any reasoned points regarding the risk taking and investment required to start the flow of “unearned income” generally get shouted down.

Our manager is currently scrambling around trying his best to reassure those “left behind” and remove some of the potential pain points. I think I’ll stick around until the weather gets nicer but there does come a point when it’s no longer about the money. My past self wouldn’t believe I’d utter such a phrase though.

The Rhino 10 December 2021

There’s a dichotomy here. My lived experience is that I believed the latter a priori, but then experienced the former when the time came..

{in·deed·a·bly} 10 December 2021 — Post author

Thanks Rhino.

I’d say wealth doesn’t automatically result in happiness, but it does allow those who have it to invest their time in activities that might.

Which makes sense if we denominate true wealth in time rather than money.

FIRE v London 11 December 2021

Great post. I love your savings vs investments graph. It looks like 2004 was a significant turning point – presumably due to something indeedably-specific, not market related.

I find one of the under-documented benefits of being ‘rich’ is letting minor financial mishaps (booking non-changable train tickets for the wrong day, etc) wash off my back. I still remember when such events would have ruined my month.

{in·deed·a·bly} 11 December 2021 — Post author

Thanks FvL. You’re absolutely right about that buffer effect having a comfortable cushion underneath you provides. A disaster of the past is a meh moment today, annoying rather than debilitating.

2004 was the first time I had my early property portfolio revalued. Back then there were no readily accessible Zoopla/Zillow style market value estimate algorithms available, so revaluations tended to be infrequent and dramatic. That revaluation led to my discovering the concept of debt recycling, extracting accumulated equity from one property to purchase more, which in turn initiated a snowball effect of wealth creation against the backdrop of a rapidly rising market.

Andrew 12 December 2021

Sarah Beeny was never smug! She tried her best to help every single one of those idiots. I absorbed much of her advice and made a decent pile along the way. Take it back! Boo!

{in·deed·a·bly} 12 December 2021 — Post author

Lol, thanks Andrew. Sarah Beeny wasn’t wrong in her messaging, gleefully delivering it time and again to punters who didn’t want to hear it.

However, if her message had been heard at the candidate screening stage rather that pre-production, we wouldn’t have had so much guilty pleasure “car crash” television to enjoy. From what I remember, the show got cancelled once the overheated property market started to slow down.

Andrew 13 December 2021

It was rebranded as Property Snakes and Ladders, but yeah, it didn’t last long. I guess there wasn’t as much appetite for the naked capitalism. Her new shows continued the renovation theme but without the selling for a profit angle.

I know it’s not the real theme of this article but if you liked those shows or have an interest in property, the BBC series Your Home Made Perfect has… ah… perfected the format. It’s really top.